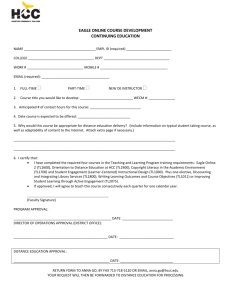

Anna of Denmark, Queen of ... 266pp, ISBN 0812235746 Biography

advertisement

Leeds Barroll, Anna of Denmark, Queen of England: A Cultural Biography (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 266pp, ISBN 0812235746 As a cultural and political force, Anna of Denmark has long been overshadowed by her husband, King James I, and their two sons, Prince Henry and King Charles I. Previous to the work of Leeds Barroll, the only biography of Anna was Ethel Carleton Williams’s Anne of Denmark (1970)—a work in which the subject is given, as Barroll laments, a rather ‘silly’ character. Rather than engage with Williams, Barroll has chosen to abandon the conventions of historical biography and attempt something different. In the opening chapter of Anna of Denmark, Queen of England Barroll explains the central theme in this ‘Cultural Biography’: ‘I am here concerned, first, with advancing the idea of Anna’s relevance to the artistic production of the very early Stuart court—a notion not readily embraced by literary scholars—and then with suggesting how our sense of the interaction between the arts and the early Stuart court may require some reconfiguration.’ For those already familiar with recent work in women’s literary history (including Barbara Kiefer Lewalksi’s excellent chapter on Anna in Writing Women in Jacobean England), Barroll’s argument will hardly seem revelatory. But what Barroll provides here, argued in clear prose and meticulous logic, and with reference to hitherto neglected sources, is a secure theoretical and historical framework from which further studies of Anna—political, biographical and cultural—can proceed. In the first chapter, which also serves for an introduction, Barroll makes a deceptively simple but crucial point: as a queen descended from a royal family, and as a consort who was simultaneously of the king and not of the king, it was to be expected that Anna should engage in cultural and political activity, and that this activity by its very nature would inevitably be distinct from, and occasionally come into conflict with, her husband’s wishes. In the main body of the book Barroll charts Anna’s queenship as it developed in three phases. In the second chapter, dealing with the period 1590-1603, he examines Anna’s time in Scotland. This period, Barroll explains, generated far more detailed records of Anna’s actions than those available for her time in England. In a series of detailed examples, featuring Anna’s links to the Gowrie conspirators and her struggle with the Earl of Mar for guardianship of Prince Henry, Barroll shows how the Scottish queen ‘played the factions that divided James’s court for her own purposes’. 3 The second phase of Anna’s queenship covers the period 1604-1614. In the more settled political arena of England, Barroll argues, Anna was compelled to construct another kind of visibility: ‘Anna turned to social and intellectual concerns that ... made her the center of high culture at the early Stuart court’. Barroll skilfully weaves his way through the genealogical maze of the Jacobean nobility to detail the familial and political affiliations of the noblewomen and noblemen Anna appointed to her court. In so doing, he argues that Anna rejected the example of Queen Elizabeth I and the prescriptions of the Privy Council by principally drawing upon relatives of the executed Earl of Essex and members of the Sidney family. As we might expect, a significant portion of these chapters deals with the magnificent cycle of the Queen’s masques—the artistic accomplishment with which Anna is most readily associated. In reading the masques, Barroll’s emphasis is not solely literary: most impressive is his clear explanation of the political statements Anna made in choosing certain noblewomen to accompany her performances, and the political statements they made in ‘taking out’ certain members of the courtly audience to participate in the dancing which concluded these entertainments. In the final chapter, Barroll considers the period 1612-1619, when Anna ceased masquing and apparently ‘withdrew’ from the court. Drawing upon contemporary letters and reports from foreign ambassadors, Barroll shows how Anna continued to be active in court politics and, perhaps more importantly, that she was perceived to be influential by English courtiers and foreign ambassadors alike. This chapter neatly complements Barroll’s account of the Scottish years, for Anna is once more shown to be concerned with two main objectives: firstly, the manipulation of peerage factions for her own purposes (this is most clearly demonstrated in Anna’s support for Buckingham at the expense of Somerset); and secondly, maintaining influence over the upbringing and households of her sons, Princes Henry and Charles. Here, Barroll persuasively argues for the centrality of Queen Anna in forming the political and cultural network so often associated with the figure of Prince Henry: ‘if an efflorescence of the arts is to be attributed to Henry prince of Wales, then ... such activity was not independently generated, but must also be re-evaluated within the joint aesthetic/political agendas of the queen consort and the heir apparent’. With such a wealth of discovery and reinterpretation, it is perhaps unkind to quibble with Barroll for any apparent omissions. Indeed, many of these ‘omissions’ are intentional, and Barroll generously points the way to further research: the intellectual interests and influence of Anna’s mother, 4 Queen Sophia of Denmark; the political and cultural interests of the women of Anna’s court; Anna’s patronage of the visual arts and music; Anna's influence upon her daughter, Princess Elizabeth, who survived to wield political influence at a court in which she was also able to support the work of artists and scientists; and Anna’s cultural influence in the Danish and Scottish courts (topics already considered by Clare McManus in her Warwick Ph.D. thesis, ‘Silenced Voices/Speaking Bodies: Female Performance and Cultural Agency in the Court of Anne of Denmark, 16031619’). The value of Anna of Denmark, Queen of England lies not simply in the undoubted quality of Barroll’s scholarship and exposition, therefore, but also in the inspiration it will provide to further work on Queen Anna. Jayne Archer University of Warwick 5