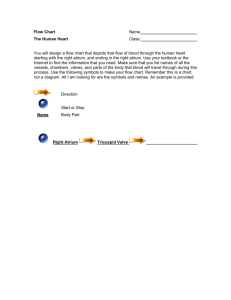

Atrium: 2014 Student

advertisement