Chapter 7 Alignment Among Secondary and Post-Secondary Assessments in Texas

advertisement

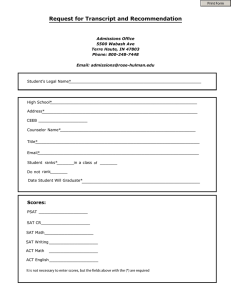

Chapter 7 Alignment Among Secondary and Post-Secondary Assessments in Texas The Texas Assessment Environment In 1986, the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board published a report entitled A Generation of Failure: The Case for Testing and Remediation in Texas Higher Education. It sounded a warning call, stating that out of the approximately 110,000 freshmen that enter Texas public college annually, at least 30,000 could not “read, communicate, or compute at levels needed to perform effectively in higher education.” As a way to address these deficiencies, the report urged that a testing program be developed to assess the reading, writing, and mathematics skills of college freshmen. This led to the development of the Texas Academic Skills Program (TASP) test, which is a 5-hour exam required of all students who plan to attend a public institution of higher education in Texas, but who have not reached a minimum achievement level on the SAT I, ACT, or Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (to be discussed later). The TASP is not an admissions test, or an exam upon which entry-level enrollment is contingent; students cannot be denied admissions to an institution based on TASP scores. Instead, the TASP is used to place students into courses commensurate with their demonstrated proficiency; those with unsatisfactory scores are assigned to remedial courses. Students must pass the TASP before they can graduate from a public two-year college or enroll in junior- or senior-level courses at a public university (see http://www.tasp.nesinc.com for details). In 1990, the Texas elementary and secondary education system launched its own high-stakes state assessment program in an effort to improve school performance and student achievement. The Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS), the program’s main testing instrument, is a criterion-referenced, multiple-choice assessment that tests students in reading, mathematics, writing, social studies, and science at various grade levels from elementary through high school. According to the Texas Education Agency, the test is supposed to represent a shift from testing basic skills to testing “higher order thinking skills and problem solving ability.” 147 Satisfactory performance on the TAAS exit level test is a prerequisite to a high school diploma.1 Students must correctly answer at least 70 percent of the multiplechoice items in reading, mathematics, and writing in order to pass. TAAS scores are highly publicized and schools are rated according to their students’ aggregate scores; low performing schools receive negative publicity and extra funds to rectify deficiencies. As an alternative requirement for the high school diploma, students may choose to take several subject-specific End-of-Course exams instead of the TAAS. The End-ofCourse exams are two-hour, mostly multiple-choice measures that assess achievement of state standards in math, English, science, and history. Students who wish to use the Endof-Course scores to fulfill their high school graduation requirements must pass the Endof-Course assessments in Algebra I, English II, and either Biology or U.S. History. Students who have passed the End-of-Course exams are exempted from taking the TAAS. However, satisfactory performance on the TAAS does not exempt students from taking the End-of Course tests, as they must also pass the latter assessments in order to gain academic credit for a particular course. In other words, passing the End-of-Course exams is a sufficient condition for graduation, whereas successful completion of the TAAS in and of itself is not. Although it is not required, students who have passed the End-of-Course test often choose to take the TAAS, as high scores on the TAAS can exempt them from taking the TASP (see http://www.tea.state.tx.us for details). Currently, Texas has adopted a new assessment system, the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS), that will replace both the TAAS and the End-of-Course tests. The TAKS will reflect state standards (i.e., Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills) and is intended to be more comprehensive and more rigorous than the TAAS. Slated for implementation in the 2002-2003 school year, the TAKS will assess high school students’ knowledge of reading (grade 9), language arts (grades 10 and 11), math (grades 9-11), science (grades 10-11), and social studies (grades 10-11). In order to receive a high school diploma, students graduating after 2004 must pass the grade 11 exit-level TAKS tests in language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies. 1 Currently, the exit level TAAS is administered at the tenth grade. If a student does not pass the test at this grade level, s/he is allowed to take the test again during the eleventh and twelfth grade, if necessary. 148 Texas Assessments Included in this Study For our study, we examined the math and English sections of the TAAS and TASP, as well as two End-of-Course exams, Algebra I and English II. We did not examine the TAKS because it was not available when this study was initiated. Although the TASP is used for placement purposes at the postsecondary level, some Texas institutions administer their own placement tests. Because the kinds of placement tests given are likely to vary by the selectivity of the institution, we attempted to obtain placement tests from both a highly selective university, and a less selective institution (Southwest Texas State University); however, we were able to obtain assessments only from the latter. In math, Southwest Texas State University administers the Descriptive Tests of Mathematical Skills (DTMS) in Elementary Algebra.2 This 35item, 30-minutes multiple-choice exam is a remedial placement measure that determines whether students possess the entry-level math skills necessary to enroll in geometry. Tables 7.1 and 7.2, organized by test function, list these testing programs and the type of information we were able to obtain for this study. For all of the tests, we used a single form from a recent administration or a full-length, published sample test. For the ELA tests, Table 7.2 specifies whether the test includes each of three possible skills: reading, editing, and writing. 2 Descriptive Tests of Mathematical Skills is published by Educational Testing Service. 149 150 College admissions State achievement Texas Academic Skills Program SAT I State achievement Texas Assessment of Academic Skills College admissions State achievement End-of-course End-of-Course Algebra ACT Test Type Test Full sample form Full sample form Full sample form Full sample form Full sample form Materials Examined 75 minutes 60 minutes 5 hours total testing time 35 MC 15 QC 10 GR 60 MC 48 MC 60 MC 39 MC 1 GR Number and Type of Items Table 150 continues No time limit 2 hours Time Limit Calculator Calculator None None Calculator Tools Selection of students for higher education Selection of students for higher education Assess whether students entering Texas public institutions of higher education possess entry level math skills Monitor student achievement toward TX standards Monitor student achievement of state-based standards Purpose Table 7.1 Technical Characteristics of the Mathematics Assessments Arithmetic (13%), algebra (35%), geometry, (26%), and other (26%) Prealgebra (23%), elementary algebra (17%), intermediate algebra (15%), coordinate geometry (15%), plane geometry (23%) and trigonometry (7%) Fundamental math, algebra, geometry, and problem-solving Fundamental math, algebra, geometric properties, and problem-solving Elementary algebra Content as Specified in Test Specifications 151 College admissions College admissions College placement SAT II Mathematics Level IC SAT II Mathematics Level IIC Descriptive Tests of Mathematical Skills in Elementary Algebra Notes. MC = multiple-choice OE = open-ended GR = grid-in QC = quantitative comparison Test Type Test Full sample form Full sample form Full sample form Materials Examined 30 minutes 60 minutes 60 minutes Time Limit 151 35 MC 50 MC 50 MC Number and Type of Items None Calculator Calculator Tools Assess student readiness for geometry Selection of students for higher education Selection of students for higher education Purpose Real numbers, algebraic expressions, equations, and inequalities, algebraic operations, data interpretation Algebra (18%), geometry (20%, specifically coordinate (12%) and three-dimensional (8%)), trigonometry (20%), functions (24%), statistics and probability (6%), and miscellaneous (12%) Elementary and intermediate algebra (30%), geometry (38%, specifically plane Euclidean (20%), coordinate (12%), and three-dimensional (6%)), trigonometry (8%), functions (12%), statistics and probability (6%), and miscellaneous (6%) Content as Specified in Test Specifications 152 College admissions State achievement Texas Academic Skills Program AP Language and Composition State achievement Texas Assessment of Academic Skills College admissions State achievement End-of-course End of Course Exam English II ACT Test Function Test Full sample form Full sample form Full sample form Full form, 1998 released exam Full sample form Materials Examined 180 minutes --60 minutes reading -- 120 minutes writing 80 minutes --35 minutes reading --45 minutes editing 5 hours No time limit 2 hours Time Limit Table 152continues 52 MC reading 1 OE reading 2 OE writing 40 MC reading 75 MC editing 42 MC reading 40 MC editing 1 OE writing 49 MC reading 40 MC editing 1 OE writing 18 MC reading 2 OE reading 18 MC editing 1 OE writing Number and Type of Items Provide opportunities for HS students to receive college credit and advanced course placement Selection of students for higher education Assess whether students entering Texas public institutions of higher education possess entry level English skills Monitor student achievement toward TX standards Monitor student achievement of statebased standards Purpose Y Y Y Y Y Reading Section? Table 7.2 Technical Characteristics of the English/Language Arts Assessments N Y Y Y Y Editing Section? Y N Y Y Y Writing Section? 153 College admissions College admissions College admissions SAT I SAT II Literature SAT II Writing Notes. MC = multiple-choice OE = open-ended Test Function Test Full sample form Full sample form Full sample form Materials Examined 60 minutes -- 40 minutes editing -- 20 minutes writing 60 minutes 75 minutes Time Limit 153 60 MC editing 1 OE writing 60 MC reading 40 MC reading 38 MC editing Number and Type of Items Selection of students for higher education Selection of students for higher education Selection of students for higher education Purpose N Y Y Reading Section? Y N Y Editing Section? Y N N Writing Section? Alignment Among Texas Math Assessments In this section, we describe the results of our alignment exercise for the math assessments. The results are organized so that alignment among tests with the same function is presented first, followed by a discussion of alignment among tests with different functions. Alignment is described by highlighting similarities and differences with respect to technical features, content, and cognitive demands. That is, we first present how the assessments vary on characteristics such as time limit, format, contextualized items, graphs, diagrams, and formulas. We then document differences with respect to content areas, and conclude with a discussion of discrepancies in terms of cognitive requirements. Table 7.3 presents the alignment results for the math assessments. The numbers in Table 7.3 represent the percent of items falling into each category. As an example of how to interpret the table, consider the SAT I results; 58% of its items are multiplechoice, 25% are quantitative comparisons, and 17% are grid-in items. With respect to contextualization, 25% of the SAT I questions are framed as a real-life word problem. Graphs are included within the item-stem on 7% of the questions, but graphs are not included within the response options (0%), and students are not asked to produce any graphs (0%). Similarly, diagrams are included within the item-stem on 18% of the questions, but diagrams are absent from the response options (0%), and students are not required to produce a diagram (0%). With respect to content, the SAT I does not include trigonometry (0%), and assesses elementary algebra (37%) most frequently. In terms of cognitive demands, procedural knowledge (53%) is the focus of the test, but conceptual understanding (32%) and problem solving (15%) are assessed as well. Results for the other tests are interpreted in an analogous manner. 154 155 MC QC 100 100 TAAS TASP 0 0 0 0 20 14 12 8 7 5 15 3 15 S 0 2 0 0 2 2 0 3 RO 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 P 3 2 26 18 13 15 22 15 S 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 RO 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 P 11 10 12 1 15 0 0 0 M MISC = 155 miscellaneous topics 0 0 0 8 0 21 12 25 G Formulas Content Areas PA = prealgebra EA = elementary algebra IA = intermediate algebra CG = coordinate geometry PG = plane geometry TR = trigonometry SP = statistics and probability 0 12 18 25 22 38 92 38 C Diagrams Formulas M = formula needs to be memorized G = formula is provided 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 OE Graphs Contextualization C = contextualized items 100 0 0 17 0 0 0 3 GR Context Format MC = multiple-choice items QC = quantitative comparison items GR = fill-in-the-grid items OE = open-ended items Notes. DTMS College Placement Test 0 0 SAT II Math 100 Level IC SAT II Math 100 Level IIC 25 58 SAT I 0 100 ACT College Admissions Tests 97 End of Course Algebra State Achievement Tests Test Format 17 2 2 13 17 17 55 5 PA 3 22 10 2 5 10 0 5 IA 6 12 12 6 15 8 2 25 CG 0 14 28 19 25 21 10 15 PG 0 18 4 0 8 0 0 0 9 6 8 13 3 10 22 8 TR SP 0 12 6 11 5 8 0 0 MISC 3 26 34 32 40 10 10 8 Cognitive Demands CU = conceptual understanding PK = procedural knowledge PS = problem-solving 97 54 58 53 53 81 90 92 PK Cognitive Demands CU Diagrams S = graph/diagram within item-stem RO = graph/diagram within response options P = graph/diagram needs to be produced 65 14 30 37 22 25 12 43 EA Content Table 7.3 Alignment Among the Technical, Content, and Cognitive Demands Categories for the Math Assessments 0 20 8 15 7 8 0 0 PS Alignment Among Tests With the Same Function State Achievement Tests Three state achievement tests are included in this analysis: the TASP, TAAS, and End-of Course Algebra. The End-of-Course Algebra is a 2-hour test, whereas the TAAS has no time limit. The TASP does not specify the amount of time devoted to assessing math knowledge, but total testing time is 5 hours. All three measures are primarily multiple-choice tests, although the End-of-Course Algebra does contain some grid-in items (see Table 7.2). All exams include many items framed in a realistic context, but there is variation with respect to extent. Contextualized items comprise 92% of the TAAS, but 38% of the End-of-Course Algebra and TASP. Questions that contain graphs within the item-stem are relatively uncommon, comprising 3% of TAAS questions and 15% of End-of-Course Algebra and TASP questions. Questions that contain diagrams within the item-stem constitute 15% of the End-of-Course Algebra and TASP, and 22% of the TAAS. None of the test include items that require a memorized formula, but items requiring a formula that has been provided constitutes 12% of the TAAS, 21% of the TASP, and 25% of the End-of-Course Algebra. In terms of content areas, the End-of-Course Algebra focuses on elementary algebra (43%), but the TAAS emphasizes prealgebra (55%). In contrast, the TASP is almost evenly split between elementary algebra (25%) and planar geometry items (21%). With respect to cognitive demands, all tests assess procedural knowledge most frequently (81%-92%). The TASP also contains some problem-solving items (8%), but the TAAS and End-of-Course Algebra do not. College Admissions Tests We examined four college admissions tests: the ACT, SAT I, SAT II Math Level IC, and SAT II Math Level IIC. All tests, except the SAT I, have a one-hour time limit. The SAT I has a 75-minute time limit. All four exams are also predominantly multiplechoice, although the SAT I includes quantitative comparison (25%) as well as grid-in (17%) items. Contextualized questions are most prevalent on the SAT I (25%) and least prevalent on the SAT II Math Level IIC (12%). Students are rarely asked to work with 156 graphs, and questions that contain graphs within the item-stem constitute no more than 12% of items on the college admissions measures. Questions that include diagrams within the item-stem are more prevalent, comprising 26%, 18%, and 13% of items on the SAT II Math Level IC, SAT I, and ACT, respectively. However, questions with diagrams are infrequent on the SAT II Math Level IIC (2%). Formulas are also uncommon, but there are differences with respect to the extent to which formulas are necessary. Whereas the ACT, SAT II Math Level IC, and SAT II Math Level IIC include some items in which a memorized formula is needed (15%, 12%, and 10%, respectively), these items are largely absent from the SAT I (1%). Although the college admissions exams generally sample from the same content areas, they do not do so to the same extent. Elementary algebra comprises most of the SAT I items (37%). The SAT II Math Level IC also emphasizes elementary algebra (30%), but focuses on planar geometry as well (28%). The ACT shows a similar content emphasis as that of the SAT II Math Level IC; 22% of its items assess elementary algebra and 25% assess planar geometry. The SAT II Math Level IIC, on the other hand, draws from more advanced content areas, such as intermediate algebra (22%) and trigonometry (18%). In terms of cognitive demands, all four tests assess procedural knowledge to a similar degree. Procedural knowledge items constitute between 54% and 58% of the items found on college admissions measures. However, there is more variation among the exams with respect to emphasis on problem solving. The SAT I and SAT II Math Level IIC place relatively greater emphasis on problem solving (20% and 15%, respectively) than do the ACT and SAT II Math Level IC (7% and 8%, respectively). College Placement Tests The only college placement test examined is the DTMS. It is a 35-item multiplechoice test administered within 30 minutes (see Table 7.2). A moderate fraction of its questions are framed in a realistic context (20%), and few of its items require a memorized formula (11%). Items rarely ask students to work with graphs (3%), but items calling for students to work with graphs are relatively more common (14%). Most DTMS test questions assess elementary algebra (65%) and procedural knowledge (97%). 157 Alignment Among Tests with Different Functions With the exception of the SAT I and End-of-Course Algebra, none of the math assessments requires students to generate their own answers. Questions framed within a realistic context represent a small to moderate proportion of college admissions tests (12%-25%), a moderate proportion of the DTMS (20%), and a large proportion of state achievement tests (38%-92%). Questions that contain graphs within the item-stem are relatively uncommon, comprising less than 15% of any assessment. Diagrams are included on every measure that we examined, but typically constitute only a small or moderate fraction of a test. Questions that contain diagrams within the item-stem represent 2%-26% of college admissions items, 15%-22% of state achievement items, and 3% of the DTMS items. Questions calling for memorized formulas are also relatively infrequent, comprising 0% of state achievement tests, 1%-15% of college admissions tests, and 11% of the DTMS. With respect to the content category, college admissions exams assess logic (coded as miscellaneous) and trigonometry more frequently than do state achievement tests or the DTMS. Excluding the SAT I, trigonometry items are included on 4%-18% of college admissions tests, but 0% of the DTMS and 0% of state achievement exams. With respect to content coverage, college admissions exams tend to assess more content areas than either the DTMS or state achievement tests, the TASP notwithstanding. College admissions exams focus most on elementary algebra (14%-37%) and planar geometry (14%-28%). The TASP is similar to college admissions measures in content coverage, and also emphasizes elementary algebra (25%) and planar geometry (21%). In contrast, the DTMS does not include any planar geometry items; instead, the majority of its items assess elementary algebra (65%). End-of-Course Algebra also focuses on elementary algebra (43%), but the TAAS assesses prealgebra most frequently (55%). In terms of cognitive requirements, all tests emphasize procedural knowledge, but to varying degrees. Procedural knowledge items are most common on the DTMS (97%), followed by state achievement tests (81%-92%), and least common on college admissions tests (53%-58%). Problem-solving items are absent from the DTMS and two of the three state achievement tests (the TASP is the exception), but constitute a small to moderate fraction of college admissions (7%-20%) measures. Conceptual understanding items are 158 not typically assessed by the DTMS (3%) or state achievement tests (8%-10%), but comprise a moderate proportion of college admissions exams (26%-40%). Discussion Below, we discuss the implications of the discrepancies among the math assessments. We begin by highlighting instances in which differences are justifiable, then address whether there were any misalignments that may send students confusing signals. We also explore the possibility that state achievement tests can inform postsecondary decisions. Which Discrepancies Reflect Differences in Test Use? As noted in Chapter 1, content discrepancies may reflect differences in intended test use. To illustrate, consider the SAT II Math Level IIC and End-of-Course Algebra. The SAT II Math Level IIC includes topics from a wide variety of courses, whereas the End-of-Course Algebra contains items primarily from a single content area. In this particular case, the two tests have disparate functions, and content differences reflect variations in purpose. The SAT II Math Level IIC is used by admissions officers to identify students who are qualified for college-level work. Because success in postsecondary math courses depends, in part, on math knowledge developed over several courses, the SAT II Math Level IIC includes items assessing an array of math topics. The End-of-Course Algebra, on the other hand, is a measure of proficiency of one specific course. Consequently, it is warranted that the End-of-Course Algebra limits its content to a narrow area of math. The above example represents justifiable discrepancies across tests with different purposes. However, there are also instances in which discrepancies within tests of similar purposes are warranted as well. For instance, that the SAT I places greater emphasis on problem-solving and non-routine logic problems, whereas the ACT places greater emphasis on procedural knowledge and textbook-like items is justifiable given that the SAT I is intended to be a reasoning measure, and the ACT is intended to assess content knowledge found in high-school math courses. 159 Is There Evidence of Misalignment? As defined in Chapter 1, misalignments refer to those discrepancies that are not attributable to test function, and therefore send students confusing signals regarding the kinds of skills that are needed to perform well on a given test. In our analysis of the math tests, we could not find any examples of misalignments, as discrepancies among the college admissions, college placement, and state achievement measures appear to have stemmed from variations in test use. Additionally, differences among tests of similar purposes are either small or moderate, or reflect nuances in purpose (e.g., see the above SAT I and ACT example). Can State Achievement Tests Inform Postsecondary Admissions and Course Placement Decisions? Although there are many discrepancies among exams of different functions, it may still be possible that a test can serve multiple purposes satisfactorily. Currently, some measures are used for more than one purpose. Many postsecondary institutions, for example, allow students to submit scores from college admissions exams such as the SAT I or ACT as a means of exemption from a remedial college placement test. Potentially, state achievement tests can be used for similar purposes. Policymakers have advocated using scores on some state achievement tests for purposes beyond monitoring student achievement (Olson, 2001b; Schmidt 2000) because such a policy change would not only reduce testing burden, but it would also motivate students to focus on state standards rather than on external tests like the SAT I or ACT (Healy, 2001; Olson, 2001a; Standards for Success, 2001). Below, we discuss the potential of the TAAS and TASP for college placement and admissions decisions. The TAAS holds little potential as a measure that can guide either admissions or placement decisions. Its emphasis on prealgebra at the expense of elementary algebra and geometry means that it cannot be used to place students into an appropriate math course, as it provides little information about students’ readiness to enroll in courses such as geometry, intermediate algebra, and so forth. Furthermore, because the TAAS is devoid of items assessing intermediate algebra, trigonometry, and problem solving, it 160 cannot distinguish among higher-achieving examinees as well as college admissions exams. The TASP, however, holds more promise as an alternative to college admissions measures, such as the ACT. It covers the same content areas as the ACT, and to approximately the same extent. Additionally, the proportion of problem-solving items on both tests is comparable. To determine the feasibility of the TASP as a measure that informs admissions decisions, more research is needed to explore the relationship between the TASP and ACT, as well as the relationship between TASP scores and firstyear college grade point average. Other factors, such as the potential of adverse impact of the use of TASP scores on different student groups, must also be considered. Alignment Among Texas ELA Assessments Below we present the ELA results. As with math, we discuss discrepancies both within and across test functions. The results are also organized by skill, namely reading, editing, and writing. In some instances, there are only two tests in a given category, so it is important to keep in mind that patterns or comparisons may not be representative of more general trends within this category of tests. Alignment is characterized by describing differences with respect to technical features, content, and cognitive demands. Specifically, we discuss differences in time limit and format, then document discrepancies with respect to topic, voice, and genre of the reading passages, before concluding with variations in cognitive processes. The alignment results for tests that measure reading skills are presented in Tables 7.4-7.5. Tables 7.6-7.7 provide the results for exams that assess editing skills, and Tables 7.8-7.9 provide the findings for exams that assess writing skills. For each table, the numbers represent the percent of items falling in each category. To provide a concrete example of how to interpret the findings, consider the content category results for the AP Language and Composition, presented in Table 7.4. With respect to topic, 50% of the reading passages included on the AP Language and Composition are personal accounts, whereas 25% of the topics are about humanities, and the remaining 25% are about natural science. It does not include topics from fiction or social science (0% each). In terms of the author’s voice, 75% of the passages are written in a narrative style, whereas the other 161 25% are written in an informative manner. With respect to genre, only essays (100%) are used; passages on the AP Language and Composition are not presented as letters, poems, or stories (0% each). Results for the other tests are interpreted in a similar manner. 162 163 43 14 TAAS TASP 20 63 SAT II Literature 0 AP Language and Composition SAT I 25 ACT College Admissions Tests 0 Fiction End-of-Course English State Achievement Tests Test 0 40 25 25 29 43 0 Humanities 0 20 25 25 29 14 0 Natural Science Topic 13 20 0 25 14 0 0 Social Science 25 0 50 0 14 0 163 100 Personal Accounts 0 43 100 40 75 0 0 0 0 0 71 50 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 60 25 50 57 29 0 Narrative Descriptive Persuasive Informative Voice Table 7.4 Alignment Within the Content Category for the Reading Passages 13 0 0 0 0 0 0 Letter 25 80 100 75 86 57 100 Essay 50 0 0 0 0 0 0 Poem Genre 13 20 0 25 14 43 0 Story Reading Measures Alignment Among Tests of the Same Function State Achievement Tests There are three state achievement measures that assess reading proficiency, Endof-Course English, TAAS, and TASP. All three exams contain multiple-choice items, but only the End-of-Course English requires students produce a writing sample that shows their understanding of a reading passage. The TAAS has no time limit, but the End-of-Course English must be completed within 2 hours, and the TASP must be completed within 5 hours. The End-of-Course English and the TASP does not contain a separate section for reading items, so it is not possible to determine amount of time devoted specifically to assessing reading skills (see Table 7.2). There is much variation with respect to the content of the reading passages. The End-of-Course English includes passages that are personal accounts (100%), written in a narrative voice (100%), and presented as an essay (100%) (see Table 7.4). Reading passages on the TAAS draws from fiction or humanities (43% each), are typically narrative pieces (71%), and are presented as essays (57%) or stories (43%). In contrast, the TASP passages tend to be essays (86%) about humanities or natural science (29% each), written in a narrative (43%) or informative (57%) voice. With respect to cognitive demands, all three tests emphasize inference (60%-79%), although a moderate proportion of items on each exam also assess recall (21%-40%) (see Table 7.5). 164 Table 7.5 Alignment Within the Cognitive Demands Category for Tests Measuring Reading Skills Test Recall Inference Evaluate Style End-of-Course English 31 69 0 TAAS 40 60 0 TASP 21 79 0 ACT 58 42 0 AP Language and Composition 23 77 0 SAT I 18 83 0 SAT II Literature 13 80 7 State Achievement Tests College Admissions Tests College Admissions Tests Four college admissions exams assess reading proficiency: the ACT, AP Language and Composition, SAT I, and SAT II Literature. With the exception of the AP Language and Composition, no other college admissions test assesses reading skills with open-ended items. Testing time devoted to measuring reading skills is 60 minutes for both the SAT II Literature and AP Language and Composition. Because the SAT I does not contain separate sections for editing and reading items, we cannot determine testing time earmarked specifically for assessing reading proficiency, although testing time devoted to assessing both types of skills is 75 minutes (see Table 7.2). Reading passage topics also vary from one measure to the next (see Table 7.4). The SAT II Literature emphasizes fiction (63%) whereas AP Language and Composition emphasizes personal accounts (50%). The SAT I favors humanities (40%), but the ACT is evenly distributed among fiction, humanities, natural science, and social science (25% each). Narrative pieces are included on all college admissions measures, and range from 40% of the SAT I passages to 100% of the SAT II Literature passages. Essay is generally the most common genre, appearing on 75% of the ACT, 80% of the SAT I, and 100% of the AP Language and Composition passages. However, the SAT II Literature is more likely to include poems (50%) than essays (25%). With the exception of the ACT, most college admission exams require students to interpret and analyze the reading passages. 165 Inference items range from 42% of the ACT questions to 83% of the SAT I questions (see Table 7.5). College Placement Tests None of the college placement tests in our sample for this case study site assess reading proficiency. Alignment Among Tests of Different Functions With the exception of the End-of-Course English and AP Language and Composition, all measures assess reading proficiency solely with multiple-choice items. Testing time devoted specifically to assessing reading skills ranges from 35 minutes for the ACT to unlimited for the TAAS. Fiction, humanities, and natural science are the most common topics, and all exams except the End-of-Course English contain reading passages from at least one of these areas. Every test also contains either a narrative passage or an informative passage, and the majority includes both. (The End-of-Course English and SAT II Literature contains only narrative pieces). Essay is the most prevalent genre, comprising 57%-100% of college placement tests and 75%-100% of college admissions tests, the SAT II Literature exam notwithstanding. Instead, the SAT II Literature favors poems. Across each test, items that assess inference skills are most prevalent and evaluate style items are least prevalent. Inference items comprise 60%-79% of state achievement measures and 42%-83% of college placement exams. Evaluate style items are absent from all reading measures except the SAT II Literature, where they comprise 7% of the test. Editing Measures Alignment Among Tests of the Same Function State Achievement Test Three state achievement tests, the End-of-Course English, TAAS, and TASP, assess editing skills with multiple-choice items (see Table 7.2). As mentioned earlier, the 166 TAAS is an untimed measure, whereas the End-of-Course English and TASP must be completed within 2 and 5 hours, respectively. Passage topics vary across measures; the TAAS favoring works from natural science (44%), but the TASP favors humanities pieces (69%). The End-of-Course English is evenly split between natural science and personal accounts (50% each) (see Table 7.6). Less variation is observed with respect to voice or genre as most are narrative pieces (50%-56%) presented as essays (67%-100%). In terms of cognitive demands, the TAAS focuses exclusively on recall (100%). The End-of-Course English also emphasizes recall (70%), but contains a moderate proportion of evaluate style items as well (30%). The TASP is almost evenly distributed among recall (33%), inference (42%), and evaluate style (25%) (see Table 7.7). 167 168 0 TASP SAT II Writing SAT I ACT 0 0 11 TAAS College Admissions Tests 0 Fiction End-of-Course English State Achievement Tests Test 100 60 69 22 0 0 N/A 20 19 44 50 Humanities Natural Science Topic 0 0 6 0 0 Social Science 0 20 6 22 50 168 Personal Accounts 50 40 50 56 50 0 0 0 0 0 N/A 0 0 6 0 0 50 60 44 44 50 Narrative Descriptive Persuasive Informative Voice Table 7.6 Alignment Within the Content Category for the Editing Passages 0 0 6 11 0 Letter 100 100 94 67 100 0 0 0 0 0 Poem N/A Essay Genre 0 0 0 22 0 Story Table 7.7 Alignment Within the Cognitive Demands Category for Tests Measuring Editing Skills Test Recall Inference Evaluate Style End-of-Course English 70 5 25 TAAS 100 0 0 TASP 33 43 25 ACT 48 4 48 SAT I 0 100 0 SAT II Writing 50 3 47 State Achievement Tests College Admissions Tests College Admissions Tests Items measuring editing skills are included on three college admissions tests, the ACT, SAT I, and SAT II Writing. The exams are predominantly multiple-choice, with testing time ranging from 40 minutes for the ACT to 45 minutes for the SAT II Writing (see Table 7.2). As mentioned earlier, the SAT I does not specify the specific amount of testing time devoted to measuring editing skills. The SAT I does not include a reading passage, but instead uses a few sentences as prompts. In contrast, the ACT and SAT II Writing include reading passages. These reading passages are typically essays about humanities, and written in either a narrative or informative voice (see Table 7.6). The ACT and SAT II Writing items are equally distributed among recall (48% and 50%, respectively) and evaluate style items (48% and 47%, respectively), but the SAT I assesses only inference skills (see Table 7.7). College Placement Tests None of the college placement tests examined in this case study site assesses editing skills. Alignment Among Tests of Different Functions Editing skills are assessed solely with multiple-choice items. All measures, except the SAT I, includes reading passages as a prompt. (The SAT I uses sentences as 169 prompts). Of those measures that include a reading passage, most are essays (67%100%), typically written in a narrative (40%-56%) or informative style (44%-60%). More variation is observed with respect to reading passage topics. College admissions exams favor humanities (60%-100%), whereas state achievement tests favor natural science, the TASP notwithstanding (44%-50%). The TASP tends to include topics from humanities (69%), although a moderate proportion of its topics also draw from natural science (19%). Most measures tend not to cover the full spectrum of the cognitive demands category. The ACT and SAT II Writing emphasize recall and evaluate style items, but are generally devoid of inference items, whereas the reverse is true for the SAT I. Both the TAAS and End-of-Course English focus on recall (100% and 70%, respectively) at the expense of inference skills (0%-5%). The TASP, on the other hand, assesses all three levels of the cognitive demands category; the test is almost evenly distributed among recall, inference, and evaluate style items (33%, 43%, and 25%, respectively). Writing Measures Alignment Among Tests of the Same Function State Achievement Tests Three state achievement tests, the End-of-Course English, TAAS, and TASP, require students to organize and support their ideas via a composition (see Table 7.2). The TAAS and TASP favors humanities as writing prompts, but the End-of-Course English favors personal accounts (see Table 7.8). With respect to scoring criteria, all three exams require students to demonstrate mechanics, word choice, style, organization, and insight (see Table 7.9). 170 Table 7.8 Alignment Among the Writing Prompt Topics Topic Test Fiction Humanities Natural Science Social Science Personal Accounts State Achievement Tests End-of-Course English X TAAS X TASP X College Admissions Tests AP Language and Composition X SAT II Writing X X Table 7.9 Alignment Among the Scoring Criteria for Tests Measuring Writing Skills Scoring Criteria Elements Test Mechanics Word Choice Organization Style Insight End-of-Course English X X X X X TAAS X X X X X TASP X X X X X AP Language and Composition X X X X X SAT II Writing X X X X State Achievement Tests College Admissions Tests College Admissions Tests Of the college admissions measures, only the SAT II Writing and AP Language and Composition require a writing sample. The SAT II Writing provides students with a one- or two-sentence writing prompt on a topic (usually humanities), and allows 20 minutes for students to respond (see Tables 7.2 and 7.8). In contrast, prompts on the AP Language and Composition are typically reading passages, and students are required to provide a total of three writing samples in over two hours (see Table 7.2).3 Topics can 3 The AP Language and Composition requires a total of three writing samples, two of which are produced during the 120-minute writing session, and one during the 60-minute reading session. However, because examinees also respond to a set of multiple-choice items during the reading session, it is unknown the amount of time students devote specifically to the writing sample. 171 vary, but are usually about humanities or personal accounts (see Table 7.8). The AP Language and Composition emphasizes all elements of the scoring criteria, but SAT II Writing downplays the importance of insight (see Table 7.9). College Placement Tests None of the college placement tests analyzed for this case study site requires a writing sample. Alignment Among Tests of Different Functions Time limits for a single writing sample can vary from 20 minutes (SAT II Writing) to unlimited (TAAS). Humanities and personal accounts are the most common topics, and every test includes a writing prompt from at least one of these areas. All tests except the SAT II Writing emphasize mechanics, word choice, organization, style, and insight as part of its scoring rubrics. The SAT II Writing downplays the importance of insight. Discussion Our discussion of the discrepancies among ELA assessments parallels that of the math discussion. We first identify examples of discrepancies that are justifiable, then discuss the implications of the misalignments. We also discuss the feasibility of using state achievement tests to inform admissions decisions. Which Discrepancies Reflect Differences in Test Use? As in math, some discrepancies among the ELA assessments reflect differences in purpose. Consider, for instance, discrepancies between the scoring standards of the TAAS and the AP Language and Composition. For the former test, maximum scores are awarded to writing samples that have minor diction errors, mechanics lapses, and underdeveloped paragraphs. Under the AP Language and Composition guidelines, such compositions might receive adequate scores, but would not be viewed as exemplary papers. Because the AP Language and Composition is used to award academic credit to students who demonstrate college-level proficiency, whereas the TAAS is used to 172 monitor the achievement of all students within the state, including those not planning to attend a postsecondary institution, discrepancies between their scoring criteria are warranted. Even when two measures have similar test functions, discrepancies may still be warranted. For example, the large discrepancy between the SAT I (100%) and the ACT (4%) and the SAT I and SAT II Writing (3%) with respect to inference items is attributable to subtleties in purpose. The SAT I is intended to be a measure of reasoning proficiency, so great emphasis on inference questions is justifiable. The ACT and SAT II Writing, on the other hand, are curriculum-based measures, so relatively greater focus on skills learned within English classes (i.e., recall and evaluate style skills) is to be expected. Is There Evidence of Misalignment? Although the vast majority of the ELA discrepancies stems from variations in test function, one instance of misalignment pertains to the scoring criteria of the SAT II Writing. Insight is included within the scoring criteria of every other writing measure we examined, but is omitted from the scoring rubrics of the SAT II Writing. Given that insight is included in the standards of most English courses, it appears that the SAT II Writing standards are incongruent with those that are typically expressed. Potentially, this misalignment can send students mixed messages about the importance of insight with respect to writing proficiency. If the developers of the SAT II Writing were to add insight to the scoring criteria, or provided a clear rationale of why insight has been omitted from the scoring rubrics, students would receive a more consistent signal about the importance of insight with respect to writing skills. Can State Achievement Tests Inform Postsecondary Admissions Decisions? As mentioned earlier, policymakers are exploring the possibility that scores on graduation tests can be used to inform college admissions decisions. In reading, that the TAAS assesses inference skills to approximately the same extent as college admission measures may suggest that the TAAS might be a viable alternative to college admissions exams. However, inference items can vary with respect to cognitive sophistication 173 elicited. A previous study by Education Trust (1999) showed that ELA inference items could vary greatly with respect to nuance of interpretations. Given the differences in the intended test uses, it is very likely that inference items on the TAAS may not be as complex as that elicited by college admissions exams. More research needs to be conducted to determine whether the TAAS can discriminate among higher-achieving examinees as well as college admissions exams. With respect to writing proficiency, state achievement tests hold more promise as alternatives to college admissions tests. Neither the ACT nor the SAT I requires a writing sample, and the SAT II Writing allows 20 minutes for a writing sample. Given the short time limit, the SAT II Writing composition represents a very limited indicator of writing proficiency. In contrast, state achievement tests allow more time for students to compose their writing sample. The TAAS, for example, is an untimed writing measure, and would arguably allow admissions officers to better judge applicants’ writing proficiency than the ACT, SAT I, or SAT II Writing. However, as discussed earlier, the current scoring rubrics for TAAS may not be rigorous enough to be of use for some institutions, especially the selective ones. Therefore, changes to the scoring guidelines may need to be implemented if the TAAS writing samples were used to inform admissions decisions at these higher-selectivity schools. Again, any policy changes regarding the use of the TAAS to inform placement or admissions decisions will require more research, particularly the relationship between TAAS scores and first-year college grade point average in English courses. 174