ARTICLES AnVANCING TOLERANCE AND EQUALITY USING STATE CONSTITUTIONS: ARE THE BOY SCOUTSPREPARED?*

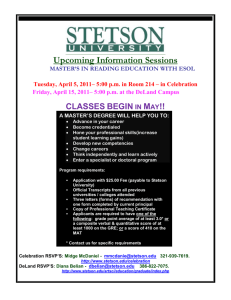

advertisement