INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION COUNCIL WORKING GROUP

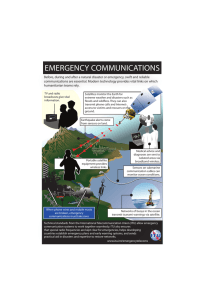

advertisement