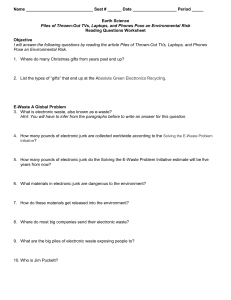

GSR 2011 Pa p e r

advertisement