Working time

advertisement

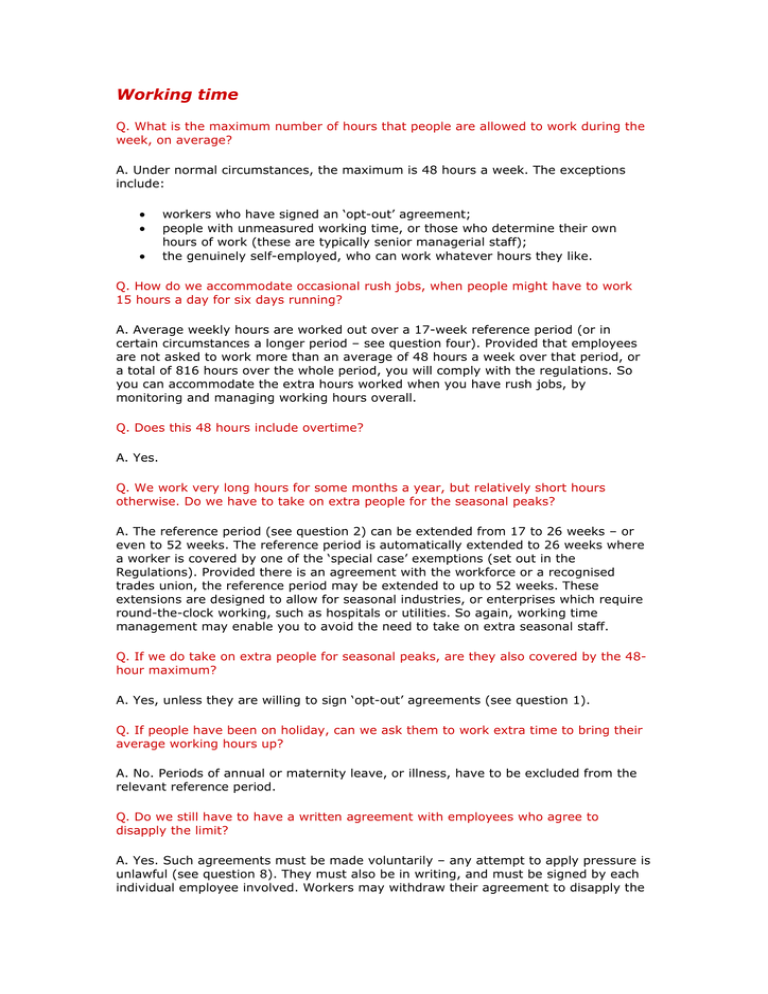

Working time Q. What is the maximum number of hours that people are allowed to work during the week, on average? A. Under normal circumstances, the maximum is 48 hours a week. The exceptions include: workers who have signed an ‘opt-out’ agreement; people with unmeasured working time, or those who determine their own hours of work (these are typically senior managerial staff); the genuinely self-employed, who can work whatever hours they like. Q. How do we accommodate occasional rush jobs, when people might have to work 15 hours a day for six days running? A. Average weekly hours are worked out over a 17-week reference period (or in certain circumstances a longer period – see question four). Provided that employees are not asked to work more than an average of 48 hours a week over that period, or a total of 816 hours over the whole period, you will comply with the regulations. So you can accommodate the extra hours worked when you have rush jobs, by monitoring and managing working hours overall. Q. Does this 48 hours include overtime? A. Yes. Q. We work very long hours for some months a year, but relatively short hours otherwise. Do we have to take on extra people for the seasonal peaks? A. The reference period (see question 2) can be extended from 17 to 26 weeks – or even to 52 weeks. The reference period is automatically extended to 26 weeks where a worker is covered by one of the ‘special case’ exemptions (set out in the Regulations). Provided there is an agreement with the workforce or a recognised trades union, the reference period may be extended to up to 52 weeks. These extensions are designed to allow for seasonal industries, or enterprises which require round-the-clock working, such as hospitals or utilities. So again, working time management may enable you to avoid the need to take on extra seasonal staff. Q. If we do take on extra people for seasonal peaks, are they also covered by the 48hour maximum? A. Yes, unless they are willing to sign ‘opt-out’ agreements (see question 1). Q. If people have been on holiday, can we ask them to work extra time to bring their average working hours up? A. No. Periods of annual or maternity leave, or illness, have to be excluded from the relevant reference period. Q. Do we still have to have a written agreement with employees who agree to disapply the limit? A. Yes. Such agreements must be made voluntarily – any attempt to apply pressure is unlawful (see question 8). They must also be in writing, and must be signed by each individual employee involved. Workers may withdraw their agreement to disapply the limit at any time, providing they give the notice required under the agreement. The maximum notice that you can request from a worker is three months. Q. Where one employee in a team refuses to work more than the statutory maximum hours, though the rest are willing, is there anything we can do? A. No. If you dismiss someone who refuses to work longer hours, or attempt to subject him (or her) to any detriment (for example, by shifting him to another less attractive job), he can take the matter to an Employment Tribunal. Any dismissal will be automatically unfair – regardless of how long the employee has been with you: he does not need the normal one year of continuous employment to put in a claim, in this case. If he complains of detrimental treatment short of dismissal, and the Employment Tribunal finds in his favour, it can award him whatever compensation it finds appropriate. Q. Is travelling time included in working hours? A. Where the work involves travelling – for example, a travelling salesman – the answer is yes; otherwise usually no. Travel between home and work is unlikely to count as working hours, though it will depend on whether the travel is undertaken in normal working time. Q. Does time spent on training count as working time? A. Generally yes, provided that the training is work-related. Q. Does lunch time count as working time? A. A normal lunch break is excluded from working time. However, a working lunch would be included (for example, a business lunch). Q. How do we deal with the hours when people are on call? A. Hours spent on call at your premises are working time. Hours spent on call away from the workplace, where the employee is free to pursue leisure activities, only count as working time for that time which is actually spent undertaking normal duties. Q. We asked people to come in over a weekend, to rescue what they could from our premises after a flood. Does the time count towards the 48-hour limit? A. Yes. With emergencies, as with seasonal work, it is possible to extend the reference period from 17 to 26 weeks. However, people who came in over the weekend would be entitled to ‘compensatory rest’ – that is, enough time off to ensure that they have at least one extra full day off per week, over the next two weeks. Q. What is the current position on paid annual leave? A. Every worker is entitled to four weeks’ paid leave per annum. This includes bank holidays and public holidays, although this is now being challenged by the trades unions in the courts. Leave accrues, at the rate of one-twelfth of the annual entitlement each month, from the beginning of the employment. It is no longer lawful to deny workers the right to leave until they have been with the employer for 13 weeks. The right to paid annual leave continues to accrue, even during periods of absence from work (for example, for illness or maternity leave). Q. How do we calculate the holiday entitlement of part-timers? A. As a minimum, they are entitled to sufficient paid leave to be away from work for four weeks, in the same way as a full-time worker. Where full-timers working a fiveday week would be entitled to 20 days’ holiday a year, a part-timer doing two days a week would be entitled to eight days’ leave. If you give your full-time workers more than four weeks paid annual leave, then your part-timers are entitled to a holiday on a pro-rata basis. Q. How many days off do people have to have during the week? A. They are entitled to at least one day (24 hours) off each week, although this can be deferred (but not abandoned) in particular circumstances: for instance, where there is a high level of seasonal work, or where round-the-clock working is required. The 24-hour break each week can (if it suits you as employer) be replaced by two 24hour breaks, or one 48-hour break (24 hours back-to-back) in each 14-day period. Q. Is the entitlement of 17 year olds different from that of adult workers? A. Yes. ‘Young workers’ (that is, workers between the ages of 15 and 18, and over compulsory school age) are entitled to two full days off a week, although this can be reduced to 36 hours, if the nature of the job makes it unavoidable. There does not have to be any compensatory rest if this happens. They are also entitled to marginally longer breaks in the working day (30 minutes), if a period of work extends to 4.5 hours. Q. We work in the catering industry and use split shifts. Apart from the 48-hour limit, are there other regulations we might fall foul of? A. Yes. Workers are entitled to 11 hours of continuous rest every day (12 hours for young workers), which yours will not be getting if, for instance, they start at midday and do not finish until the small hours. Moreover, if they work late on several nights a week, you might be caught by the regulations on night working (see next question). Q. Is there a limit on the amount of night-time working that we can ask from our employees? A. Yes. Employees who regularly work upwards of three hours a night between 11 am and 6 am will be classified as night workers. Night workers may not work more than eight hours a night, averaged over 17 weeks (or more than eight hours in any night in hazardous occupations, where no average applies). They must be offered a free health assessment before they start working nights, and further free health assessments regularly thereafter. In many cases, once a year would be appropriate. Q. What does the annual health assessment for night workers entail? A. The first stage should preferably be a health questionnaire, which should be drawn up with the help of a doctor or nurse who knows what the health effects of night time working are likely to be. If the answers to the questionnaire raise any doubts about the individual’s fitness to work at nights, or suggest that his (or her) health may be suffering because of night time working, the employer must then offer that employee a free medical examination, and act on the findings if necessary. You have to take particular care with new and expectant mothers, and with ‘young workers’. You cannot wait until a worker requests an assessment – you must offer one.