Discipline and grievance issues

advertisement

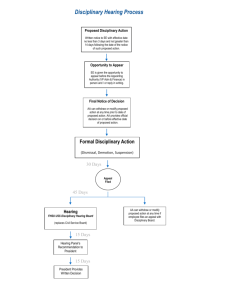

Discipline and grievance issues Q. Do we have to have written disciplinary rules? A. It depends on how big your business is. If you have more than 20 employees (including part-timers and contract workers), the answer is yes. Moreover, you must tell employees, in your terms and conditions, where they can find the procedure. If you have less than 20 employees, you are not (at present) required to have a written procedure, although this exemption is due to be removed under the provisions of the Employment Act 2002, which are expected to come into force in 2004 (see below). However, if disciplinary action on your part ever lands you in front of an Employment Tribunal, you will certainly have a stronger case if you can show that you followed a fair procedure. Another advantage of having a set disciplinary procedure is that all parties will know what to expect if you have to take disciplinary action. Under the Employment Act 2002, certain minimum requirements in respect of dismissal, disciplinary and grievance procedures will be implied into all employment contracts. The changes were due to be introduced in 2003 but the Government has deferred implementation until 2004. If you are planning to introduce or amend disciplinary rules in the near future, take legal advice. Q. What should we include in our disciplinary procedure? A. The procedure should let employees know how you will deal with disciplinary matters. This must include the fact that before any disciplinary action is taken employees will be given an opportunity to state their case, and will have the right to have a colleague or trade union representative present. The procedure should also set out the employees’ right to appeal against any disciplinary action taken against them. You should set out some examples of conduct which would result in disciplinary action. It would be a good idea to cover rules relating to work and work performance — for example timekeeping, absenteeism, negligence, sub-standard work, and disregard of health and safety requirements. In addition you would need to cover conduct more generally — for example theft, fraud, offensive behaviour (such as harassment, abuse and violence) and inappropriate behaviour (such as drinking, drug taking or smoking in prohibited areas). Depending on the nature of your business, you might need to identify other forms of misconduct. For example, you might need specifically to state that it will be misconduct to breach the employer’s rules on how employees use computers and the Internet (to protect the business against viruses and legal risks). Do not try to be too prescriptive, or people might simply take it as a challenge to beat the system. Moreover, you need flexibility to cover new situations. Give examples of the rules, but make sure they are clearly indicated as examples. Q. How should we categorise disciplinary offences? A. There is a big difference between poor timekeeping and selling the company’s secrets or stealing its computers. You could classify some offences (for example, inappropriate dress) as misdemeanours; some (for example, poor timekeeping, smoking in prohibited areas, less serious breaches of health and safety rules) as misconduct, and some (for example, violence, drunkenness, sexual harassment) as gross misconduct which merits instant dismissal. You might also want to include another category for repeated misdemeanours (for example, persistent poor timekeeping). Q. How do we go about drawing up a disciplinary procedure? A. It is advisable to get it done by specialist employment lawyers, particularly in view of impending changes in the law (see question one). However, you can find the crucial elements set out in the Acas Code of Practice. In essence: the procedure must be set out in writing; it must provide for a speedy resolution of the problem; it must identify employees’ rights – in particular, their right to give their side of the story, to have matters investigated before any action is taken, to be given adequate notice of any disciplinary hearing, and to be accompanied at that hearing by a colleague or union representative; it must say what actions could be taken; it must provide for a right of appeal. Q. How many warnings do we need to give an employee? A. Your procedure could follow four steps: verbal warning; written warning; final written warning; and dismissal. Each step will involve a disciplinary hearing. Within the minimum requirements imposed by new legislation (see question one), reserve the right to enter the procedure at any stage depending on the severity of the offence. For example, you might want to move straight to the dismissal hearing in the case of gross misconduct. Q. How do we ensure that our disciplinary procedure does not lead to any legal problems? A. More precise requirements may be set out in new legislation (see question one), but for the time being, the key is to be reasonable, fair and consistent. If, for example, an employee made a claim of unfair dismissal against you, an Employment Tribunal would check whether: the rules were reasonable; the employee knew about them; the rules avoided being discriminatory; the rules were applied fairly and consistently; a fair procedure was followed; the circumstances and degree of the offence were taken into account. Q. What offences justify immediate dismissal? A. Immediate dismissal will only be justified for the most serious offences – for example, theft, taking bribes, or sexual harassment – which constitute gross misconduct. Once you have concluded your disciplinary procedure, you can dismiss the employee without notice. Be careful. The fact that you consider an offence to be gross misconduct does not mean that an Employment Tribunal will agree with you. The Tribunal will decide whether your response falls within the band of reasonable responses open to an employer. If it falls inside the band, it is fair; if it falls outside the band, it is unfair. Q. Do we need a formal grievance procedure? A. You are required to state in your terms and conditions of employment who your employees can go to if they have a grievance. This requirement is likely to be amplified in the near future by the provisions of the Employment Act 2002. In practice a grievance may often precede a resignation and a possible claim for discrimination or constructive dismissal. It is therefore a good idea to have a grievance procedure which sets out how such complaints will be dealt with – following the procedure will help you to show the Employment Tribunal that you dealt with the employee’s concerns. Q. What kind of problems are likely to be raised as grievances? A. It will vary from business to business, and could cover anything from arguments over who washes up the tea mugs to resentment over favouritism or poor management. But changes in working practices, terms and conditions (including pay), and problems over personality clashes are common. It is important not to ignore grievances, no matter how trivial they may seem. Not only can they affect productivity and morale, but you could risk serious legal complaints such as discrimination or constructive dismissal. Q. What are the key elements of an effective grievance procedure? A. More precise requirements may be set out in new legislation (see question one), but for the time being it is important to set out the grievance procedure clearly, and ensure that it is universally available. Make sure that employees know who to approach with any grievance. Typically, a grievance is initially taken to the immediate supervisor. The grievance can then, if necessary, be taken further by putting it in writing to a more senior manager. If that fails to resolve the problem, a final decision is taken at the highest level. Set a short deadline (say five days) for responding to complaints at each stage, but allow yourself some flexibility. You must allow (and should encourage) employees to bring a colleague or union representative (who may put forward their views) to any meetings at which grievances are being discussed. Q. How do we introduce new disciplinary rules? A. New legislation is likely to establish that certain minimum disciplinary standards must be implied in all contracts of employment in the near future (see question one). Allowing for this, however, it is advisable to say in your terms and conditions that you expect employees to adhere to your disciplinary rules, but do not make the disciplinary rules and procedures themselves part of the terms and conditions. Otherwise you could find yourself in breach of contract if you fail to observe some details of the rules and procedures that you have established. Q. Should we make adherence to the disciplinary rules a condition of employment, and include them in the contract of employment? A. New legislation is likely to establish that certain minimum disciplinary standards are implied into all contracts of employment in the near future (see question one). Allowing for this, however, it is advisable to refer to the disciplinary and grievance procedures in your terms and conditions, but do not make the disciplinary rules and procedures themselves part of the terms and conditions. Otherwise you could find yourself in breach of contract if you fail to observe some details of the rules and procedures that you have established. Q. Should we make adherence to the disciplinary rules a condition of employment, and include them in the contract of employment? A. New legislation is likely to establish that certain minimum disciplinary standards are implied into all contracts of employment in the near future (see question one). Allowing for this, however, it is advisable to refer to the disciplinary and grievance procedures in your terms and conditions, but do not make the disciplinary rules and procedures themselves part of the terms and conditions. Otherwise you could find yourself in breach of contract if you fail to observe some details of the rules and procedures that you have established. Q. What do we do if an employee claims a rule is unreasonable? A. Consider carefully what he (or she) has to say. If you insist on him observing the rule, and he insists on flouting it, the matter could eventually end up in front of an Employment Tribunal. In that case the extent to which you have been reasonable in applying the rule in the first place, and then in responding to any challenge, will be critical to the outcome. Q. What do we do if an employee claims not to have known the rules? A. Investigate. It is unreasonable to expect employees to observe rules they do not know about. But if the rule was well publicised, and/or the employee has been picked up before for failing to observe it, he will not be able to rely on ignorance. Q. Do we have to apply the same rules consistently to all employees? A. It is important to be consistent, but it is even more important to be reasonable. You should investigate the circumstances in each case, and also consider any mitigating factors. It is quite possible that an offence (for example, drunkenness) that would merit instant dismissal in one employee (a young man who comes in fighting drunk) would merely merit a reprimand in another (an older man with long service, who comes in somewhat merry after celebrating a family event). If you do end up treating different employees differently for the same offence, however, you do need to be able to explain and justify exactly why. Q. What do we do if an employee breaks a rule – but claims that ‘everyone does it’? A. Is he right? If you have been turning a blind eye to other employees breaking the rule, it would certainly be unfair to make an example of this employee. If the rule is important, you will have to re-emphasize it, giving everyone fair warning that failure to observe it will be penalised in future. Q. What do we do if there are extenuating circumstances for a disciplinary offence? A. Take them into account in deciding what penalties to apply. Keep good records of the extent to which you are doing so. It is not necessarily reasonable to apply the same penalty to the same offence in different circumstances (see question 15), but if you are going to treat employees differently you need to be able to explain why. Q. What should we do if an ex-employee claims to have been unfairly dismissed? A. Get immediate advice from specialist employment lawyers. They will need to respond within three weeks to an IT1 (see Employment tribunals, HR 21). They can assess the merits of the case, and if they think your ex-employee is simply trying it on, apply to have the case thrown out. If it is more serious than that, they may advise you to see whether you can conciliate through Acas. Q. What do we do if an employee continually finds excuses to avoid disciplinary hearings? A. Be reasonable. If the excuses are genuine – for example, certified sickness – be patient. If there is no good excuse, hold the disciplinary hearing in the employee’s absence – but warn them that you are going to do so in advance. Q. What do we do if we think that an employee is guilty of gross misconduct, but we cannot prove it? A. Weigh up the risks, and if necessary investigate further. If you take disciplinary action and are sued for unfair dismissal as a consequence, you have a defence if you can prove that you investigated thoroughly, and acted in a reasonable belief of guilt on the basis of that investigation. You will not be expected to prove the employee’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt. If you are right, the employee is unlikely to go to an Employment Tribunal; but if you are wrong and he (or she) does, the Tribunal is most unlikely to find in your favour if you have sacked someone on a mere presumption of guilt. If a criminal offence is involved (for example, theft) consider calling in the police. Take legal advice.