Discipline and grievance issues

advertisement

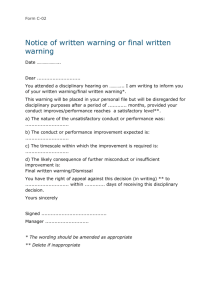

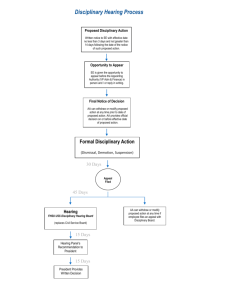

Discipline and grievance issues Disciplinary issues can result in unfair dismissal cases, if mishandled. Grievances can lead to low productivity, unwanted resignations and even constructive dismissal cases, if ignored. To stay on the right side of the law and help both sides apply consistent standards, disciplinary and grievance procedures are a vital part of the management toolkit. This briefing covers: ◆ The legal basics. ◆ Key disciplinary areas. ◆ Creating and using disciplinary procedures. ◆ Handling employee grievances. The legal requirements A Your employees’ written terms and conditions must give basic information about disciplinary rules. B ◆ Terms and conditions must say who an employee can apply to when appealing against a disciplinary decision — and how such an application can be made. ◆ If there are written disciplinary rules, the terms and conditions must say where employees can read them. Every company must state in employees’ written terms and conditions who an employee can apply to with a grievance. ◆ C Recent cases make it clear that employees have a legal right to redress for grievances. Having and following written procedures makes good business sense. ◆ If employees know and accept the rules, they are less likely to break them. ◆ If there is no outlet for grievances, small grumbles may grow. ◆ Written procedures will help you defend any employment tribunal cases that arise. Employees are more likely to accept rules and procedures if they are consulted when you are writing or amending them. D New legislation on dismissal, disciplinary and grievance procedures will come into effect in October 2004. ◆ It will establish certain minimum procedures which the aggrieved party must follow before taking matters any further. Your procedures must be equivalent, or better. ◆ In particular, any disciplinary action which is likely to result in anything other than a warning or suspension on full pay, must ◆ normally involve a three-stage procedure. ◆ Repeated minor offences. The problems must be set out in writing and the employee must be given time to think about his or her response. ◆ Misconduct. ◆ Gross misconduct. ◆ There must then be a face-to-face meeting. ◆ The employee must be given the opportunity to appeal if necessary. Only in exceptional circumstances will you be able to avoid the three-stage procedure, though there is a ‘modified’ (two-stage) version for some misconduct cases. The idea is to slow down the escalation of problems, or stop them altogether, before they get to court. Laying down the law A Identify the areas in which you need disciplinary rules. Typically these will be: B ◆ Work performance, including sub-standard work, slacking, poor timekeeping, absenteeism, negligence and reckless disregard for safety or hygiene regulations. ◆ Theft, including pilfering and fraud. ◆ Offensive behaviour, including abuse, harassment, discrimination and violence. ◆ Inappropriate behaviour, including drinking, drug-taking, gambling, smoking in prohibited areas, misuse of company facilities or, perhaps, inappropriate dress. Decide how you are going to classify different offences. In many small businesses, this will involve using four categories: ◆ C Determine what constitutes misconduct — ie behaviour that is unacceptable to you or unacceptable in the context of work. ◆ You may want to spell out rules completely banning gambling, cash collections and the distribution of political literature, or enforcing a ‘clear desk’ policy. ◆ But many rules will be matters of degree. (For example, how will you define persistent lateness?) ◆ Negligence can be covered by your disciplinary procedure, but you must treat people absolutely consistently (see 3D). D Define what acts are so serious that they constitute gross misconduct — entitling the employer to jump straight to the final stage of the disciplinary procedure and dismiss an employee without notice (although fair procedures must still be followed). ◆ Typical offences are dishonesty, theft, taking bribes, gross insubordination, falsifying company documents, fighting, abuse of drink or drugs, using someone else’s password, introducing viruses into the company’s computers, downloading Internet pornography, sending malicious emails, and racial or sexual harassment. ◆ Particular industries and companies will have their own sacking offences. ◆ Beware of jumping to conclusions. You cannot sack an employee who has been charged with theft without your own investigation. The fact that an offence is listed in your handbook as gross misconduct is not conclusive. A tribunal will decide for itself whether the offence was ‘gross’ and if the employer’s response was reasonable. ◆ In some gross misconduct cases, consider suspending the employee — on full pay — for a period while you investigate. Review the suspension regularly to assess whether it is still appropriate. Make it clear this does not constitute disciplinary action or indicate you think the employee is guilty. Minor offences and misdemeanours. Unfair dismissal? Nearly half of tribunal cases are unfair dismissal claims. In judging any claim by an employee dismissed after disciplinary action, the tribunal will run through what amounts to a checklist. A Were the rules reasonable? B Did the employee know about them? C Did the rules avoid being inherently discriminatory? D Were they applied fairly and consistently? E Was a fair procedure followed? F Were the circumstances and degree of the offence taken into account? This question may be asked even where a policy states dismissal is mandatory. Handling disciplinary issues Avoid breach of contract claims, by not making your disciplinary procedure part of employees’ contracts (except where you cannot avoid it — see Employment contracts, HR 4). But do page 2 make people aware of the rules and what happens if they are broken. A Issue a company handbook, or a separate document, listing examples of misconduct and gross misconduct, and explaining how they will be handled. ◆ B Make it clear these lists are not exhaustive. Minor issues (eg occasional lateness) can often be tackled informally, without triggering the disciplinary procedure. Make it clear that employees will not be dismissed for a first breach of discipline, unless there has been gross misconduct. F Provide a right of appeal, and explain the process involved. Acas has issued a new draft code, to guide people through the legislation coming into effect in October 2004. See www.acas.org.uk/ publications/pdf/cp01.2.pdf ◆ Discuss the problem, giving the employee a chance to tell his or her side of the issue. Using disciplinary procedures ◆ Explain that this is not a warning, but that you will keep a file note of the meeting. A Disciplinary procedures must be used if an offence is grave enough for formal action to be considered. Your procedure should include four steps: Appraisals offer a chance to deal with minor disciplinary problems and defuse grievances. C E For serious or repeated offences, follow the formal procedure. D Apply your rules consistently. ◆ E ◆ Verbal warning. ◆ Written warning. ◆ Final written warning. ◆ Finally, dismissal or other action. For example, suspension without pay, fines or transfers, demotion or loss of privileges — but only if these penalties are provided for in the contract of employment. Do not give one person a warning and just correct another in a similar situation, without clear justification for doing so. Do not give untrained managers the power to make major disciplinary decisions. ◆ Many cases are lost because managers depart from accepted procedures. ◆ Anyone launching any disciplinary action should read the Acas handbook, Discipline at Work (0870 242 9090). Procedures in any disciplinary matter which is likely to give rise to anything other than a warning or suspension on full pay must be equivalent to, or better than, the new statutory requirements from October 2004. B The Code of Practice Set the timescale for the stages of the disciplinary procedure. ◆ Leave a stated amount of time for improvement between warnings. For performance issues, the time given might vary with different types of work. A PA might be given a week to improve, but a senior sales manager six months. An employee disciplined for offensive behaviour or bad timekeeping could be expected to behave better straight away. ◆ Tribunals always insist that both the time allowed and the degree of improvement demanded must be reasonable. Your guide to disciplinary procedures is the Acas Code of Practice. Tribunals must refer to it in all disciplinary dismissal cases and at any other time when it appears relevant. To comply with the Code of Practice, you should: A Put your disciplinary procedure in writing. B Say what disciplinary actions may be taken and provide for issues to be resolved quickly. C Say who has the authority to take action. C D Tell employees about their basic rights. These include the rights to: If an employee’s behaviour or performance fails to improve after appropriate warnings, there may be no alternative to dismissal. ◆ Know the complaints against them. ◆ Ensure you have followed your procedure. ◆ Give their side of the story. ◆ ◆ Have matters investigated, in an unbiased way, before disciplinary action is taken. Give appropriate notice, in line with statutory rights or the employee’s contract. ◆ You will usually have to pay compensation if you want someone to leave immediately, except in gross misconduct cases. ◆ Whenever you dismiss an employee, give ◆ Be accompanied at hearings by a union representative or work colleague. ◆ Be given an explanation for any penalty. page 3 the reasons in writing and enclose copies of any supporting evidence. This will often deter the employee from bringing a claim. C Devise an action plan for improvement to tackle ongoing problems. D Explain the employee’s right to appeal. ◆ ◆ To guard against accusations of bias, appeals should be handled by a senior employee who was not directly involved. In a very small company, there may be no authority higher than the person who imposed the original disciplinary decision. Facing up to grievances A The most common grievances relate to new working practices, terms and conditions (including pay) and personality clashes. B If possible, deal with grievances informally. ◆ ◆ Pay particular attention to any new evidence brought forward at an appeal. Refusing to allow an employee to use the appeals procedure may lead to greater liability if an unfair dismissal claim is made. E Keep a detailed log of all disciplinary action and full records of steps taken to investigate and address the causes of the problem. C Aim to settle each grievance as near the point of origin and as quickly as possible. D Do not ignore grievances, or problems will fester, affecting productivity and morale. ◆ Employees may leave, and you risk claims for constructive dismissal. ◆ Resentment over lack of training or promotion, or alleged victimisation, may lead to complaints to a tribunal. The disciplinary hearing A Give the employee at least three clear working days’ notice of a formal hearing and written details of the issue. B Respect the employee’s rights (see 4D). C Make clear the consequences if there is no improvement (eg penalties or dismissal). Formal grievance procedures A At present, grievance procedures in small businesses commonly have three stages. D Compose any written warning after the hearing, not before, accurately reflecting the warning given at the interview. ◆ Verbal warnings are usually valid for three to six months, while final warnings may remain in force for 12 months or more. ◆ State the duration of any written warning in the warning letter. ◆ If there has been extremely grave misconduct, you may state that the final written warning will never be erased and any repeat will be grounds for dismissal. B Give a first warning, but accompany it with the offer of training. ◆ Counselling may be worth considering, if family difficulties or illness underlie behaviour and performance problems. Stress that it is the behaviour you are attacking, and not the person. The employee starts by approaching his or her immediate supervisor. ◆ The employee puts the grievance in writing and seeks action from a manager. ◆ If the problem cannot be resolved, the employee takes it to the highest level, where the decision will be final. B Respond to grievances within a time limit. For example, undertake to respond, at each stage, within five working days. C Keep your disciplinary and grievance procedures separate. ◆ A Be constructive and positive. ◆ ◆ New grievance procedures, coming into effect in October 2004, require a three-stage process similar to that for disciplinary matters. The problem must be set out in writing, there must be a face-to-face meeting, and the employee must have the opportunity to appeal against the outcome. Going for improvement Aim to improve behaviour or performance, not to punish the employee. If a grievance seems irrational or trivial, try to find the real problem behind it. Anyone who can successfully claim to have been victimised for using a grievance procedure will usually win a tribunal case. D An employee has the right to be accompanied by a colleague or union representative when a grievance is discussed. E Collective grievances are usually presented by a union or employee representatives. page 4