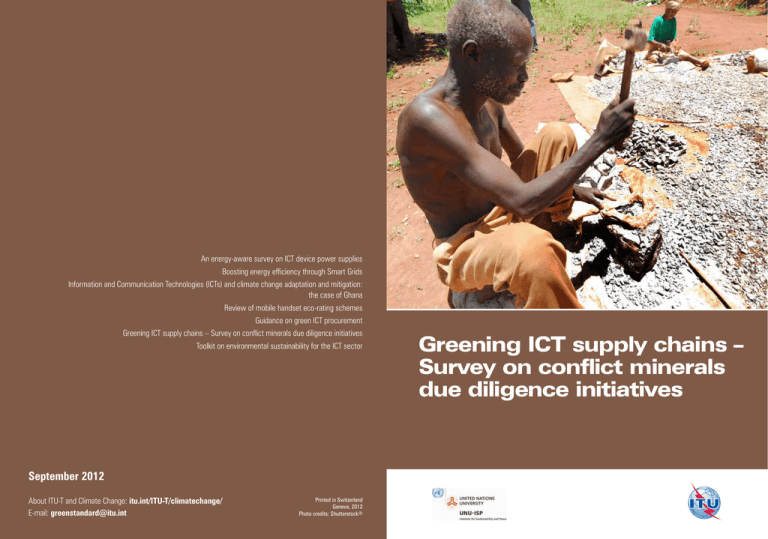

An energy-aware survey on ICT device power supplies

advertisement