A Study into the Disposable Products Stream in Smith College

A Study into the Disposable Products

Stream in Smith College

Kelly Aguilar (in collaboration with Caitlin Gossett)

Smith College

May 7, 2004

Keywords: disposable products, solid waste stream, elimination, recycling, purchasing

Abstract

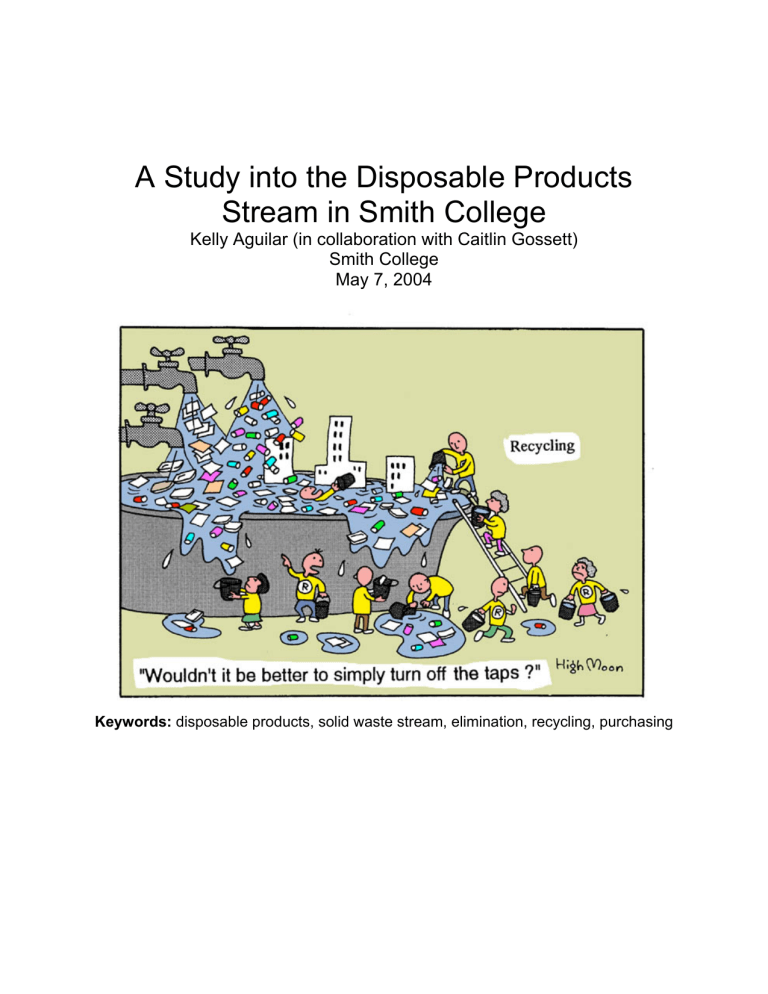

Waste accumulation is an issue that the world population faces in the 21st century and one that is increasing exponentially. With increased demands from populations for governments to find a solution, many environmentalists are turning to institutions to determine the best course of action. Smith College is a leading liberal arts institution that prides itself in being the forefront of women’s education and progress. However, in sustainability Smith is behind in comparison to other schools and requires massive overhauls, to achieve similar levels. While radical changes need to occur within the institutions prioritization towards environmentalism some changes can be implemented now that would provide some relief to the increasing cost of waste transportation on campus. One potential outlet we studied was the use of disposable products (paper cups, plates, napkins, plastic utensils, and bowls). We completed an in-depth survey through Dining Services and individual dining halls to determine the amount of disposable products used. This allowed us to determine what the best course of action was in terms of elimination, recycling, or purchasing. We also looked at other institutions to determine how effective their waste policies were in comparison to Smith College. Overall, current disposable products used on campus are extremely harmful to the environment and provide equal or more cost to the college. In contrast, other options create little to no waste.

Introduction

Waste is an ever present problem, particularly for environmentalists, because it grows exponentially with the population and there seems to be little effort to find methods to reduce through alternatives or education. Various studies have demonstrated that this decade in comparison to previous has the highest waste production with highest concentrations found within industrial nations (CIWMB, 2004;

EPA, 2004). In the United States, 200 million tons of waste produced out of which 82 million tons were compromised of paper and paperboard (CIMWB, 2004). While paper is a large portion of the waste stream, another important component is plastics, which have been estimated by the Environmental Protection Agency to compromise from 14 to

21 percent of the municipal solid waste stream (MWS) equal to almost 25.4 million tons

(EPA, 2004). One problem lies in that the production of these products is linear--virgin material (trees or petroleum) are consumed. These raw materials are either not

replaced or only partially and as the materials are refined a large amount of energy is consumed increasing not only waste down the stream but pollutants found in the atmosphere and ground. These two major components produce a deficit and recovery rates through recycling still represent a relatively small return in contrast to how much finishes in the MWS, which is further aggravated by the fact that energy consumed and pollutants in the environment cannot be retrieved once dispelled. Recycling of plastics overall in 1999 was 1.4 million tons, almost 5.6%, while almost 37% of paper waste is recycled (EPA, 2004). The low amount of recycling occurring and the large amount of resources being used to continue production of these products makes it imperative that current and future generations search for alternatives in order to decrease production rates and increase recycling.

Another factor in diverting all potential recyclables from the recycling stream is found in that most plastics that can be treated in recycling facilities are only level 2 and below. Approximately 19,400 U.S. communities collected plastics for recycling, primariy

PET and HDPE bottles (EPA, 2004). What determines what the “recyclability” of a plastic is based on the amount of resin present which also represents how durable the plastic is. PET or polyethylene terephthalate (i.e. soda bottles and HDPE or highdensity polyethylene (i.e. milk jugs) tend to have a lower percentage of resin signifying that during their manufacturing the reaction required to produce the product was not irreversible as occurs for higher resin content plastics which produces a more durable plastic used for plumbing, cars, and housing (EPA, 2004). Paper also can be diverted from the recycling stream if it is contaminated with food or any other product which would render it un-recyclable according to each facilities standard. This creates a

problem in that all potential recyclable items are not recycled but rather can end up in the waste stream where their degrading time can be more than a century.

According to David Orr (2002), in The Nature of Design , university campuses are the breeding ground for discovering these new solutions. Orr’s point is that radical changes need to be made at the institutional level to make conscientious choices to become more sustainable and be responsible not only for the immediate needs but for the greater world. Yet it is important to note that he feels that while these larger changes are implemented, smaller ones need to begin to make that shift in thinking occur. It is not necessary to develop a new idea rather it is necessary to become better observers of our surroundings and see where sustainable changes have been implemented and work seamlessly with the community that had previously been unaware of environmental impact their practices had.

On the Smith College campus sustainability has been a difficult concept to sell both to the student population and the institution largely due to the up front cost involved since most of the technologies are still in development and tend to be expensive, both with the initial purchase and maintenance fees. Therefore, Smith needs to look at ways to implement changes that have little effect to the infrastructure already in place, but that would yield high impact on campus sustainability. These changes would also assist in increasing campus awareness of waste and the effects Smith College has on the greater environment, both positive and negative. A college student alone produces almost 640 lbs. of waste per year and at Smith alone 4 tons of waste are sent to the landfill weekly (Columbia University, 2000; Wraight, 2003). One of the areas where we observed high amount of waste being produced was from disposable products. From personal observation in dining halls many students tend to use disposable products both for hygienic reasons as well as for convenience and these are valid reasons for distributing disposable products throughout the campus population. Therefore, we

decided to look at how much of disposable products is actually being used (volume and cost) and determine greener alternatives that would be both cost-effective and environmentally friendly.

Methodology

In order to determine the amount of disposable products being used in dining halls at Smith College we needed determine both yearly and monthly rates of disposable products in each dining hall. This would allow an understanding of the rates of use and allow us to determine the amount of money being budgeted for solely disposable products. This would give us both an average volume and cost of disposable products for both the wide campus as well as the individual dining halls. We would retrieve this information from interviews with Dining Services personnel.

We also needed to determine what use rates were for a dining hall during a week. This would permit us to understand what trends were involved with use either during weekdays when classes were in session or weekends when students spent more time studying. Therefore, we would look at our respective houses (Chase/Duckett and

Gillett) during the week of April 11-17, 2004 and look at the amount of products remaining in a case (looked at cups, plates, and utensils) after dinner. This allowed us to look at how much a house uses during a week and determine if usage was high or low dependent on weekday or weekends.

In order to create a full web of how much and when disposable products were used we needed to determine the source of these products and their final destination.

Interviews with Dining Services would provide information about distributors. Looking at packaging would provide both brand name and which company produced them.

Research on the internet would provide where these companies made their products and where most of these products ended up after use. This would allow an

understanding of where Smith College fit within a disposable products life from its production to final resting point, if this existed.

These three survey point would allow us to determine which alternatives would best fit Smith College and prove most effective both in cost and sustainability.

Results

Interviews with Kevin Martin, involved with purchasing for Dining Services, revealed an abundant amount of information. Our distributor is Vistar, which is responsible for bringing all disposable products on campus. However, our products are produced at different locations. We found that our plates, cups, and bowls were made by International Paper, Co. and our utensils (Dixie™) and napkins (Coronet™) where made by Fort James Corporation and intermediate company for Georgia-Pacific, Co.

International Paper, Co. holds both its headquarters and production line in Stamford,

CT, while Georgia-Pacific, Co. produces its Dixie™ and Coronet™ products in

Leedsminister, MA. This signifies that the overall cost of our current disposable products must include not only production cost but also transportation cost of these products from their production site to their storage area to their consumer and eventually the landfill and based on loose estimates an individual cup would cost more than $5,000 based on gas cost and landfill fees, but excluding environmental impact cost, which cannot be currently determined based on available information ($1.844 per gallon of gas based on May 3,2004 listing and mileage based on distance from

Stamford, CT to Hartford, CT (88.6miles) then to Northampton ,MA (34.26 miles) and landfill fees at $100/ton).

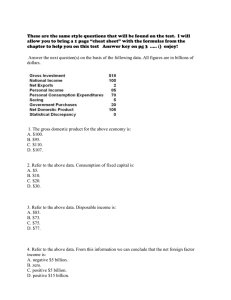

We also learned from interviews with Martin that average use of disposable products is relatively high with almost 55,000 paper cups and 63,000 plastic utensils being used on average per dining hall in 2003 (Table 1). However, the pattern from our study on weekly use in our own dining halls seems to demonstrate the use occurs

largely during the weekends (Figure 1). This demonstrates that use of disposable products is high but increases almost two-fold during the weekend (Figure 1; Table 2).

We also found that both plastic and paper disposable products have a longer cycle from production to final destination and invoke both high energy and raw material costs which end up for the most part in the MWS (Figure 2), which would also need to be included in cost of current disposable products.

Furthermore, looking at average use we found that despite the relative low cost of purchasing disposable products to greener options the amount of waste produced cost more to send to the landfill in contrast to the zero amount of waste produced from the greener options (Table 1; 2; 3). However, what the cost difference would be cannot be determined due to the unavailability of information pertaining to the environmental impact extraction of raw materials, transportation, long-term effect of these extractions, production, consumption, landfill, atmospheric and land effect, etc. Alternative solutions used in other institutions have demonstrated to be both more sustainable and despite having high up front cost have lower overall cost since current practices must factor the afore mentioned factors (Table 4). Furthermore, alternatives can be implemented into recycling systems already in place on campus, such as composting, and produce no waste, but must include transportation cost which can offset the positive effect of using these products (Table 3; 4).

450

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

M T W Th F Sa Su

Weekdays

Figure 1. Usage of paper cups in Chase/Duckett and Gillett Houses throughout the span of a week of April 11-17, 2004 from counting amount of cups remaining after dinner (Diamonds- Chase/Duckett; Square-Gillett)

Figure 2.

Web illustrations of the life cycles of a) plastics and b) paper.

Figure 2a. Cycle demonstrating how recycling of plastics occur and the input of both recycled plastics and virgin plastic pellets in plastic production. (Image retrieved from http://www.plasticomnium.com/services/Recycl/RE_IN_01.htm

)

Figure 2b. Demonstrates the process from 1) wood cut down for paper production, 2) wood pulped in paper mill, 3) paper reels produced from both virgin and recycled sources, 4) used to make both paper and paperboard products, 5) these products are used in packaging and other areas, 6) partial recycling used in energy production, 7) other paper is collected, 8) recycling of paper that is returned to production (Image retrieved from http://www.watermanswebworld.com/code/education.html

).

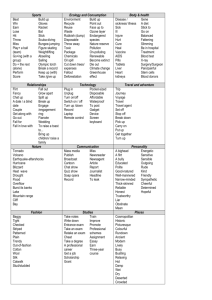

Table 1.

Amount and cost of disposable products used on average per house between

January 2003-December 2003 (Source data from interview with Kevin Martin, 2004)

Cost

Case Purchased

500 26 114 2964 Plates

Bowls

Lids

Napkins

Cups

Spoons

Knives

Forks

5000 28 247 6916

1000 35 55 1925

21 32 672 1000

1000

1000

Table 2.

Total average use of disposable products in Chase/Duckett and Gillett dining halls during the span of the week of April 11-17, 2004 (Source data from interview with

Kevin Martin, 2004)

Plates

Cups

Quantity

500 70

1500 200

Utensils 1000 130

Table 3.

Cost analysis for greener disposable products from Green Home, Inc. based on Smith College average usage (excludes bowls and lids). (Source data collected from Green Home,Inc. website, 2004)

Item Count per Amt/ Cases Cost $

Case Case

$

Plates

Napkin

1000 90 114 10260

6000 54 247 13338

Cups

Spoons

Knifes

Forks

35 31 1085

Table 4.

Potential alternatives that would be more sustainable based on options already implemented in other institutions of either the same size or larger and the cost and impact these options would have if implemented at Smith College.

Institution(s) Plan Retail Price $* Est. Cost $ ** Environmental Impact

McGill

University,

Hampshire,

Oberlin, Bates,

Rice, Clark GA,

Bowdoin,

Mount Holyoke,

Amherst

Mount Holyoke,

Amherst

Reusable

Travel Mugs

Limited Access

(students would be required to demonstrate need for disposable product either due to scheduling conflict, etc.)

~16.00-20.00

Variable, dependent on college purchasing practices (at a high acceptance an almost 50% decrease in use could be expected since students would need to prove an explanation)

~52,000 (all upfront)

Curren t

~10,000

(Dependen on student t acceptance and only 50% of campus demonstrated need)

Eco-Friendly

Choice

~16,000

(Dependen on student acceptance and only 50% of campus demonstrated need) t

•

Zero

•

No

•

No Landfill fees

•

Transportation fees

•

Replacement fees (if the college decides to assist students)

With Eco-friendly choice

•

100%

Biodegradable

•

Composting

•

No Landfill fees

•

Transportation fees

•

Not harming loca l or global environment through use o unsustainable materials f

:

Smith College

(Hubbard and

Capin)

Honor Mug

System

Free of charge N/A •

•

No upfront cost

No transportatio n fees

•

No Landfill fees

•

Enhances recycling from products already in the students

• grasp strong hygiene regul ation

* Based on extensive internet search on various commercial companies that provide these services

** Based on a set student population of 2,600 and extrapolation from that point forward.

Discussion and Recommendations

Our study found that there are many changes that need to occur in Smith

College in order to reach the goal of being a sustainable campus. Based on our findings we have determined that current purchasing practices are at an extremely high rate with 28,500 cups being distributed and disposed of by the student populatio n per week not including other disposable products which would top a total of 57,000 disposable items being used weekly by the student population. If the cost of one cup exceeds $5,000 based loosely including gas cost, landfill fees and production cost but excluding environmental impact cost, which would roughly increase the price at almost

$10,000 (based on the doubling price if impact cost was equivalent to current retail cost for all fees afore mentioned), demonstrates that alternatives need to be implemente d.

Conducting a cost analysis of alternative products would reduce landfill fees and a partial amount of environmental impact but would still include all other fees which may prove to not be the best sustainable option available. However, a more in-depth survey on total cost of disposable products is required in order to asses a comprehensive cost analysis of all aspects involved in disposable products from source to final destination.

Since curren t data did not provide cost and would have been difficult to determine under this study.

Our study also found that disposable products are largely used during the weekends and account for almost half of total products used. This signifies that products are largely used when almost half of the student population dines outside o f their residences and study in exterior locations since a large amount of dining h alls close during the weekend and consolidated dining is implemented. This trend demonstrates that students largely utilize disposable products when food services are a t a distance from their residence and finding an alternative that would address this ne ed may serve to decrease the pattern of use. However, it is important to note that the

study did not determine how much of product use can be attributed to houses tha t have no dining services forcing students to commute to dining halls. This may have a significant impact on overall product use and if it can be a ttributed to this then changes could be potentially implemented in these residencies.

Based on our findings and coupled with previous studies conducted for EVS 300 implementing any change could prove to be extremely positive (Wraight, 2003; Elmer,

2003). Trends demonstrate that if policy is implemented the student population tends to follow, such as the enactment of pay-for-paper policy implemented in 2004 acade mic year coupled with paperless month campaign by GAIA (environmental group on campus) which has significantly reduced total paper waste (Personal observation).

Based on our study fall into three categories:

we believe that the best recommendations that we can make

1) Elimination: Remove all disposable products while providing substitutes such a s mugs that when used at the student cafe would receive a 10% discount and also consistent use would be promoted since other options would become unavai lable. This program could be coupled with a campaign to initiate campus awareness of environmental issues and specifically explaining why disposable products have been removed and the overall impact these have on both the local and global environment.

This program could be implemented through a slow phasing out of disposable products such as limited access leading to an eventual complete removal of all products and the replacement with mugs such as already used in McGill, Bates, etc. or the Honor Mug

System used in Hubbard and Capin House.

2) Recycling: Napkin composting would provide immediate assistance in the amount of waste sent out of the college such as the one implemented at Bates College. However, a more comprehensive infrastructure for recycling that would remove more trash c ans from all areas on campus and replace them with recycling bins would provide an

increased rate of recycling and less amount of recyclable material entering the wa ste stream. This is specifically important within the residences where recycling bins, located on the 1 st

floor of every house, are less accessible in comparison to trash cans , located on each floor. Furthermore, switching disposable products that can be in the recycling stream would be an improvement from current products which due to their wa x covering cannot be recycled and any contaminated (food, etc.) paper products cannot be recycled. Striving to find alternatives that would enter the recycling stream woul d be extremely b eneficial and compliments our third alternative of switching purchasing practices.

3) Purchasing: Choosing to purchase biodegradable products coupled with limited availability policy would minimize the high cost of these products while at the same time increasing student understanding of true limitations of world resource. Furthermore, th e impact of making this type of purchasing choice would increase awareness within the institution and would move the college in a greater way towards a more sustainable campus than the other options do. Purchasing impacts directly the economic heart o f college policy and would reflect a greater commitment on behalf of the institution to strive to sustainable practices as well as ensuring that students understand why these choices are being made. Furthermore, changing purchasing would either comp lement any of afore mentioned alternatives as well as increase rates of recycling and c omposting while decreasing waste and maintenance cost.

Literature Cited.

A guilar, Kelly. Interview with Kevin Martin. Rec. 1 April 2004. Email. Smith College

Dining Services Purchasing . 30 Belmont, Smith College.

California Integrated Waste Management Board Plastics Information and Resources

Site . April 15, 2004. California State Website. 2 8 April 2004

< http://www.ciwmb.ca.gov/Plastic/Recycled/>

Columbia Trash into Cash for Nonprofits Site. 2000. Columbia Univ ersity Website. 28

April 2004 <http://www.columbia.edu/cu/cssn/greens/waste.html>

Elmer, Kate. 2003. Sustainability at Smith Project: Environmental Impact in Smith

R esidences . Unpublished report. 14 pp.

G reen Home, Inc. Website.

May 3, 2004 <http://www.greenhome.com/>

Orr, David W. 2002. The Nature of design : ecology, culture, and human intention .

O xford University Press, New York, NY.

United States Environmental Protection Agency Municipal Solid W astes Site . April 23,

2004. Environmental Protection Agency Website . 28 April 2004

<http://www.epa.gov/epaoswer/osw/index.htm>

<http://www.epa.gov/epaoswer/non-hw/muncpl/paper.htm> (Paper)

< http://www.epa.gov/epaoswer/non-hw/muncpl/plastic.htm> (Plastics)

W raight, K. 2003. Wasting Away . Unpublished report. 14 pp.