Sustainable Land Development in Northampton, Massachusetts: Limiting Sprawl

advertisement

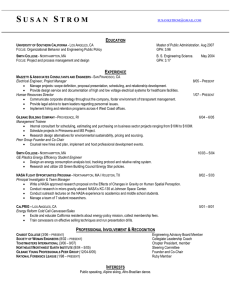

Sustainable Land Development in Northampton, Massachusetts: Limiting Sprawl Stephanie Duryee May 4, 2005 Smith College EVS 300 Professor Smith Final Project Abstract This paper is an examination of the City of Northampton’s sustainable land development. I looked at city regulations, bylaws and practices in determining how successful Northampton can be at achieving sustainable land development. I also looked at the intentions of Northampton by exploratory its smart growth goals. Next I looked at the steps Northampton has taken to embrace these goals and what steps it could take. I found that Northampton has a clear plan for smart growth but is not immune from sprawl. Limiting sprawl is an excellent way to ensure that land practices of Northampton will be sustainable. The best way to do this is to purchase conservation land and there are ways to obtain funding through this at the Federal, State and local level. The way to protect the most land, for the longest time, is to involve the community in purchasing conservation land, and limiting its own sprawl. Sustainable development is best accomplished on the local level and my findings support this conclusion. Introduction and Purpose The objective of this project is to analyze and promote the sustainable use of limited resources. I chose land in Northampton as a limited resource and focused on limiting sprawl as a way to promote sustainability. This project has significance for me not only because I am a student in Northampton, but also because I grew up in the outlying areas of Northampton where suburban sprawl is at its worst. As a kid I saw first hand as houses were developed in forests and fields that I played in with my friends. I also chose this topic because it weds my major, Government, with my minor, Environmental Science and Policy. This paper explores where 2 growth is located, allowed and promoted in Northampton; where growth should be located; and how it should be limited. This paper also touches upon state and federal influence through its guidelines and funding. The Open Space and Recreation plan and Vision 2020 are the two primary sources that I used in assessing what the smart growth goals of Northampton are. Wayne Feiden, the Director of the Northampton Planning Department was my source on what development looks like in the city and what steps are being taken to achieve the goals laid out by the two plans. The Problem of Inefficient and Unsustainable Land Use in the United States: Sprawl Land in the United States is being developed at an astonishing rate. As of January 2005, the amount of land used by urban and suburban development is 64 million acres and has increased by almost 300 percent since 1955. The population since this time has only increased by 75 percent. The pace of land development has been accelerating in each successive decade since the 1950s (Ewing 2005, 9). In Massachusetts the rate of land lost to development is forty acres per day (Hardy 2004). David Suzuki adds that, “At the very time that family sizes have dropped precipitously in North America, the average house size has almost doubled from 1,100 in 1949 to 2,060 square feet in 1993” (Suzuki 1997, 23). What these numbers suggest is that people are spreading out and consuming more land than they used to. This phenomenon is often labeled as sprawl. According to the non-governmental organizations that put together a publication entitled, Endangered by Sprawl: How Runaway Development Threatens America’s Wildlife, sprawl is characterized by the following four traits: “low-density residential development; rigid and large- 3 scale separation of homes, shops, and workplaces; a lack of distinct, thriving activity centers, such as strong downtowns or suburban town centers; and a network of roads marked by very large block size and poor pedestrian access from one place to another” (Ewing 2005, 19). Sprawl is a problem because it expands the ecological footprint that humans have on the world. A bigger footprint will put additional pressure on wildlife and their habitats, which will drive more species towards extinction and limit the populations and viability of those that remain (Ewing 2005, 12). It is important to protect ecosystems in large tracts of land but protecting land in and around cities and suburbs is also crucial in the plight for biodiversity conservation. These areas serve as buffer zones and as connecting corridors between other open space lands. As a point of clarification ‘open space’ will be used from this point forward to mean any piece of land that is undeveloped by residential or industrial development. Reasons for Protecting Open Space and Limiting Sprawl It is important to conserve open space for a variety of reasons, some anthropocentric, some biocentric. Without going into too much detail, open space provides many services that humans rely on. Protecting watersheds purifies drinking water, helps prevent against droughts, protects against floods and helps maintain a stable climate (Ewing 2005, 15). Protecting a diversity of species, and their habitats, ensures that the careful balance that nature rests on is preserved. When a species goes extinct it can cause a chain reaction that can affect an entire ecosystem (Ewing 2005, 16). Sprawl has been shown to lead to an increase in greenhouse gases, which creates a higher level of ozone degradation and generally promotes climate change. This is because of the 4 increase in travel time that people who live in suburban communities experience. These same people also participate in more traffic accidents (Ewing 2005, 19). Another benefit that humans receive from protecting open space is that the taxes generated by new residential development in outlying areas almost never are sufficient to cover the costs of extending roads, sewers, schools and other public services (Ewing 2005, 17). There are biocentric arguments to be made about the inherent value, worth and dignity of the ecosystems as well. Deep ecology is one ideology that subscribes to a biocentic point of view. This ideology states that, “The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves. These values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes” (Foundation for Deep Ecology 2005). This ideology is not incompatible with land planning that has sustainability as a goal as both humans and biodiversity would benefit. Sprawl can be controlled by using land that is already developed sustainably; and limited by allowing new development to be pursued only in accordance with a policy of ‘smart growth’. Smart growth consists of many different elements but most basically it is the efficient use of land and a revitalization of existing residential areas rather than building outward onto open land. In Northampton there are smart growth initiatives that have been developed by both the Massachusetts state government and the federal government. In addition to providing smart growth guideline, funding is also given to the through these channels. The Role of the Federal Government in Promoting Smart Growth 5 The federal government is involved in promoting smart growth very indirectly. Northampton receives $1.5 million in block grants for community development. While this money is meant for the promotion of affordable housing, open space acquisition, and limiting the energy used in the city, it is up to Northampton to determine how it is best spent (Feiden 2005). The federal government also provides programs and services that communities can apply for. Northampton is not currently a part of the following programs but is eligible. The United States Environmental Protection Agency has an initiative where communities can apply for help in developing a community plan and in some cases will receive additional funding for showing achievement in smart growth (EPA 2005). Federal funding assistance for smart growth is available through the United States Department of Agriculture. Two projects that communities can apply for are: the Resource Conservation and Development project and the Soil and Water Conservation project. The first project aims to “improve the capability of State and local agencies and local nonprofit organizations in rural areas to plan, develop and carry out programs for resource conservation and development.” The second project aims to provide “technical assistance to the public in planning and applying natural resource conservation practices, systems, and treatment; and furnishing information to State and local governments” (EPA 2005). The Department of Commerce offers a Public Works and Development Facilities Program which aims to provide assistance in “economic development, including sustainable development” (EPA 2005). The Role of the Massachusetts Government in Promoting Smart Growth 6 The State of Massachusetts is more involved than the federal government in promoting a program of sustainable development. In fact the State has defined sustainable development as being an idea that is also called smart growth, and is about, “developing where and how it is most appropriate for our communities and natural environment. It is an alternative growth model to the more typical decentralized automobile-dependant, single-use model of sprawl development that consumes large amounts of open space and farmland, overburdens existing infrastructure, exacerbates tight municipal budgets and resources, and strains environmental integrity” (EOEA 2005). Governor Mitt Romney has articulated Sustainable Development Principles for the State's environmental, transportation, housing, and energy agencies. These principles seek to promote: “Brownfield redevelopment, compact development, the reform of local zoning laws, regulatory and permitting clarity, the preservation of open space, and renewable energy.” Further, the Governor maintains that the State will “promote development and redevelopment in and around our urban centers, and aims to pursue an aggressive growth agenda that preserves community character, history, and quality of life. In order to achieve these goals development must be promoted in and around our urban centers, as well as balanced and coordinated access to housing, employment, transportation, and natural and recreational resources (EOEA 2005). The State finances towns and cities so that they can pursue projects that are in line with the aforementioned goals. Northampton is supported by the State through the Community Development Plan program. Executive Order 418 provides up to $300,000 in aid to assist communities with the development of a community plan. This plan includes three elements and is meant to be a preliminary step in the creation of a “master” plan. The three elements that must be included are as follows: “Location, type, and quantity of new housing units, including housing 7 affordable to individuals and families across a broad range of income; location, type, and quantity of open space to be protected including identification and prioritization of environmentally critical unprotected open space, land critical to sustaining surface and groundwater quality and quantity, and environmental resources; location, type, and quantity of commercial and industrial economic development” (EOEA- CT River Valley 2005). Overall Northampton receives $900,000 from the State for land planning (Feiden 2005). A program that Northampton has applied for but not yet fully received funding for is the Commonwealth Capital program. This program measures how well all communities in the State are developing sustainability and then provides the top scoring cities with funding. Out of a possible 140 points, Northampton scored the highest in the state with 129 points (Knox 2005). State legislation that has affected Northampton’s land development is Massachusetts Law 40, section 5 that was enacted in 1957. This law allows towns and cities to establish Conservation Commissions "for the promotion and development of the natural resources and for the protection of the watershed resources." The mandate is to protect, acquire, educate about and manage natural resources, open space, and sensitive local resources (Conservation Commission 2005). Regulatory Challenges to Limiting Smart Growth The City of Northampton relies on funding from the State and Federal governments for the purchase of open space and to carry out its planning objectives. This funding is not guaranteed however because of the political system that underlies it. Currently there are budget deficits running at both the state and national level. Compounding this is the administrator in 8 charge of the State and National government. The governor of Massachusetts is responsible for setting the budget of the state. Past governors have set aside a significant amount of money in the budget for the conservation of open space. Governors William Weld, Paul Cellucci and acting Governor Jane Swift all expended an annual $50 million dollars for land conservation. Additionally, these three governors developed plans for the conservation of 100,000 acres for each of their tenures (Hardy 2004). With the election of Governor Mitt Romney in November 2002 all of this changed. Romney promptly stopped all acreage goals and instead rewarded communities for increasing housing production. For the fiscal year 2004 Romney only approved $18 million dollars for land conservation. This number was finally increased to $27 million due to the overwhelming negative public response (Hardy 2004). President Bush has also presented regulatory challenges to Massachusetts in the conservation of land as it the responsibility of the executive branch to set the budget for federal agencies. This means that the EPA, USDA, DOC and other agencies that have a hand in funding state and city conservation efforts are reliant upon the administration for the amount of money that they will have available. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said that President is the worst environmental president in history and confirming this are the budget cuts that he has enacted for environmental programs (Ewing 2005, 43). The President is also responsible for appointing the top officials at all federal agencies who set the annual agency agenda. Bush has put pro-business officials in charge of regulating the very industries that they come from. The agenda at the EPA has had a marked anti-environmental sentiment, which can also be seen by the regulations that Bush’s officials have passed, or have rejected (Davidson 2003). 9 While the State and Federal government provide guidelines and funding for developing smart growth plans each individual city is responsible for the actual development of a plan and then its implementation and enforcement. Land use decisions are given over to city governments because of Massachusetts’ history of “home-rule”. Home-rule means that the state allows cities and towns to pass local environmental bylaws (Hardy 2004). Thus, Northampton has the largest impact on its own growth and development. The City of Northampton’s Role in Planning Land Use and Development Northampton has five boards that make the development decisions. These boards are politically appointed, usually by the mayor, and confirmed by the City Council. The five boards are: the Planning Board; the Zoning Board; the Conservation Commission Board; the Central Building Architecture Board; and the Elm Street Historic Board. The Northampton Planning Department advises the boards but ultimately they make the decisions. The City Council oversees all decisions made by the boards (Northampton Planning 2005). Northampton has seven political wards and so the Northampton City Council is comprised of seven councilors. These seven people not only oversee land planning decisions but they also oversee zoning changes in the city. Zoning cannot be changed without a two-thirds vote of City Council (Feiden 2005). Zoning is significant in the development of land because these bylaws and ordinances affect the shape of the city more than anything else (Skelly 2003). Zoning is the allowed use of land in the city. (See Attachment 1) Zoning is a means of controlling and planning future land uses. Zoning in Northampton began in 1927 to maintain the health, safety and welfare of residents. In this way industrial plants that may generate harmful 10 emissions are not allowed in a residential area. However, zoning in Northampton was done on an ad hoc basis and without a Master Plan (as advocated now by the State). Residential areas have different size allowable building lots depending on what the zone is. In downtown Northampton the lots are considerably smaller than in the outer lying areas of the city (Feiden 2005). History of Northampton as it Relates to Land Use The history of Northampton’s economy and population sheds light on the development of land uses. Northampton is 35.7 square miles or 22,881 acres. Approximately fifty percent of the land is a mixed deciduous forest. Several thousand more acres are agriculture lands, wetlands and abandoned fields. This means that the majority of Northampton’s land area has not been developed (Open Space 2000). (See Attachment 2) The economy of Northampton has changed significantly since the end of World War II. The industrial component of the economy has receded and in its place, the commercial and service sectors of the economy have grown (Open Space 2000). Most of the city’s development occurred in a corridor along the Mill River and other level areas of the city northeast of the Mill River. Downtown Northampton, Bay State, Florence, and Leeds are all located within one mile of the historical Mill River. The Mill River was diverted from downtown in 1939 to control floods. The economic success of downtown has helped keep people centered there. There is also a commercial center in Florence that services the needs of people in that neighborhood (Open Space 2000). This makes a positive contribution to smart growth because a strong commercial center will attract and keep people living and shopping locally. 11 Residential development has changed, mostly since World War II, with suburban development transforming the Ryan Road, Burts Pit Road, Florence Road, and Westhampton Road (Rt. 66) areas (Open Space 2000). This development can all be considered to be sprawl. Not only is located away from the city center, which makes driving a necessity, but each house is situated on a large plot of land with an expansive lawn. All of the new developments on Westhampton Road, which number about seven, are cul-de-sacs, which are a signatory mark of suburban sprawl. (See Attachment 3) Northampton's overall population has not increased significantly, but a dramatic decrease in family size has created a corresponding increase in the number of households and, therefore, the number of housing units. The combination of this trend and a major decrease in the number of people living in institutions (State hospital, VA hospital) has fueled most of the last 20 years of residential development (Open Space 2000). Northampton’s Smart Growth goals: Open Space and Recreation It is with this history of land use and residential development in mind that Northampton produced the documents that outline the smart growth goals of the city. The first document, called the Open Space and Recreation Plan: 2000-2004 is revised every five years. This began in 1975 and incorporates public participation. The second document is called Northampton Vision 2020 and was written in 1999 (Open Space 2000). The purpose of the Open Space plan is that it: “provides guidance on how the city can best use limited resources to meet Northampton's open space, conservation and recreation needs. The City recognizes that the demand for open space and recreation areas exceeds what is 12 available. Rapid suburban development, escalating land values, open space loss, shrinking wildlife habitat and limited financial resources combine to limit the availability of open space and recreation areas” (Open Space 2000). The goals of the Open Space and Recreation plan are: “(1) to expand open space and recreation; (2) preserve traditional land use patterns without creating sprawl; (3) and to preserve natural and cultural resources and the environment” (Open Space 2000). Initiatives and Progress in Meeting the Goals of Open Space In order to accomplish the first goal the city aims to: preserve and expand city holdings of open space, wild lands and small pieces of open land in developed areas; use open space and recreation to ensure that the urban and village centers are attractive places to live, work and visit; make more natural areas available for public use; provide recreation opportunities for individuals of all ages and physical abilities now and for future generations; preserve the character of rural areas, farms, forests, and rivers (Open Space 2000). Northampton has taken steps to act upon the aims of the first goal with the eleven conservation areas that the Conservation Commission owns. These areas include: Fitzgerald Lake, Robert’s Hill, Mineral Hills, Sawmill Hills, Pine’s Edge, Barrett Street Marsh, Brookwood Marsh, Elwell Island, Mary Brown’s Dingle, Rainbow Beach, and the Mass. Audubon Arcadia. The land conserved with these properties is 1,252 acres. Arcadia is the largest with 766 acres total, but it is shared with the town of Easthampton (Massachusetts Audubon Society 2005). Fitzgerald Lake is 40 acres in itself but the entire conservation area is about 500 acres in size, which makes it Northampton’s largest conservation area (Conservation Commission 2005). 13 According to the Northampton Planning Department’s planning director, Wayne Feiden, the City Council does not seek out conservation efforts on its own or participate in fundraising efforts, but when it is presented with land that has the funding to be conserved they will approve it (Feiden 2005). In order to accomplish the second goal the city aims to: “redevelop vacant land in builtup areas, guarding against sprawl; promote new villages (commercial, residential areas) where feasible; foster continued mixture of uses in villages: Florence, Leeds, and Bay State; discourage development damaging village character of urban/residential neighborhoods; ensure new downtown development meshes with architectural heritage; maintain clear distinction between rural, suburban, and urban areas; promote traditional neighborhood development patterns” (Open Space 2000). To accomplish this goal Northampton has planned the “smart” development of the state hospital land. The proposal for the development of the 536.53 acres that is the state hospital land, includes the protection of 404.83 acres (75%) of open space. The residences that would be built there would be in accordance with limiting sprawl as they are located downtown and would be zoned in an urban residential zone (Open Space 2000). In order to accomplish the third goal the city aims to: “protect important ecological resources, including surface and groundwater resources, plant communities, and wildlife habitat; the city should take lead in protecting architectural and cultural history; preserve ecological and wildlife linkages, especially water-based linkages” (Open Space 2000). Northampton’s Smart Growth Goals: Vision 2020 14 Northampton’s second document outlining the city’s intentions and goals for smart growth is Vision 2020. Vision 2020 was finished in 1999 and intended to be the first step of a two step process. Unfortunately the funding needed for the second part was taken away. Wayne Feiden, Northampton’s planning director is hopeful that the next step, the implementation of the first step, will be fulfilled in the next year (Feiden 2005). Vision 2020 outlines the following goals: GOAL 1: Maintain Vibrant Urban and Village Centers GOAL 2: Encourage Economic Expansion and Job Creation GOAL 3: Enhance Residential Neighborhoods and Housing GOAL 4: Improve Multi-Modal Circulation and Parking Systems GOAL 5: Calm Traffic to Preserve Neighborhoods and Villages GOAL 6: Expand Open Space and Recreation GOAL 7: Preserve Traditional Land Use Patterns without Creating Sprawl GOAL 8: Enhance Services and Facilities for Quality of Life GOAL 9: Preserve Natural and Cultural Resources and the Environment So far the city planning department has mapped out current and future bike paths and pedestrian sidewalks to encourage sustainable transportation. City Regulatory Tools to Promote Smart Growth and Limit Sprawl Land development is restricted on land that has been identified as a wetland or watershed protection area. There are clear city regulations pertaining to these areas. Northampton also has 15 three important bylaws at its disposal to regulate and control future development. These are the Site Plan Review bylaw, the Transfer of Development Rights bylaw, and the Cluster Zoning bylaw. The Site Plan Review is used as a technique for providing the Planning Board with municipal review and oversight on projects. Without site plan review, municipalities are limited to health and safety issues in the review of proposed projects. With site plan review, review authority is expanded to include impact considerations such as vehicular and pedestrian circulation, noise, design, water pollution, scenic views and natural topography. This bylaw is limited to projects such as large subdivisions, multi-family housing projects, commercial and industrial projects (Skelly 2003). The next bylaw is the Transfer of Development Rights. This bylaw allows the city to encourage new development to located in a preferred development area rather than on natural or historic resources. Development is restricted in areas labeled “Resource Protection Area” and transferred to downtown Northampton (Skelly 2003). The city has not taken full advantage of this bylaw, but can in the future because it already exists on the books (Feiden 2005). The last bylaw of the three is perhaps the most important for limiting sprawl. Cluster Zoning is also know as Open Space Zoning, and allows smaller residential lots so long as a required amount of acreage is set aside as permanent open space. The open space is either owned by the municipality or a non-profit organization and continues in use for agriculture, recreation, scenic views, the protection of archaeological sites or other benefits (Skelly 2003). The Mineral Hills area on Sylvester Road in Northampton was acquired through this process. When the zoning of the city allows for large residential lots, the Planning Board has the ability to offer developers incentives to cluster development closer to downtown. Developers are offered the incentive of being able to build more houses (on smaller lots) when they are 16 downtown, then few houses on larger plots of land. Some other incentives the city uses are a shorter or simplified review process. The fee and review process is a way that development is discouraged by the city, although neither of these things are so monumental as to actually stop development (Feiden 2005) (Skelly 2003). Other conservation tools that city planners have are the placement of roads, water lines and sewer lines. (See Attachment 4) Developers are very unlikely to build on land that cannot be accessed by road and does not have access to water or sewer mains. It is highly uneconomical and would require much time and effort to try and have the city build these services. The planning department is very aware of the power of this tool and has it used it to keep development close to downtown (Feiden 2005) (Northampton Planning 2005). Promotion of Smart Growth Initiatives Beyond the City Government While Northampton has tools and bylaws at its disposal to discourage development in land that is currently unprotected open space (See Attachment 5), the fact remains that development cannot be halted. The best way to ensure that sprawl is limited is to protect land so that it will not ever be developed. There are several ways that this can be accomplished. The first way is for the city to purchase it with the explicit intent of conserving it; this is done by the Conservation Commission with state and federal money. Most of the land that is protected in Northampton is city land. (See Attachment 6) Another way to protect land is for private land trusts to become involved. The Broad Brook Coalition of Northampton fundraises money and then gives it to the Conservation Commission. They were instrumental in the acquisition of 17 Fitzgerald property and to date have added 148 acres to the city’s conservation land (Conservation Commission 2005). Importance of Public Participation The best and most effective way for smart growth initiatives to take hold is for the citizens of Northampton to become involved. This passage on sustainable communities makes the point that: “Because there can be no permanent solutions in a world that is ecologically and culturally dynamic, these choices will have to be made again and again as circumstances evolve. Therefore, moving toward sustainability will require a radically broadened base of participants and a political process that continuously keeps them engaged. The process must encourage the perpetual hearing, testing, working through, and modification of competing visions at the community level” (Prugh 2000, xiv). For both the Open Space and Recreation plan and Vision 2020, Northampton held public sessions where the input of community members was recorded (Open Space 2000) (Vision2020 1999). This is an excellent start to a program of citizen involvement. Public participation is vital for sustainability because a democratic government is based on the will of the people. City councilors listen and act upon the will of their constituents. Additionally, land conservation is expanded by private land donations, private financial donations and local land trusts. An example of a local land trust is the agreement of a resident farmer to keep the land as farmland. Beyond this, sprawl will be halted when the demand for it no longer exists. This requires an education and public participation process in Northampton but also nationwide. Often times new development in Northampton is the result of out-of-town citizens moving in. This kind of 18 education could come from a variety of sources, and indeed could be the topic of a lengthy discussion, but as it relates to the City of Northampton citizens must be contacted, encouraged and enticed to participate in the conservation process. Suggestions for Increased Public Participation Suggestions for increased public participation are: Northampton could hold conservation meetings, beyond the Vision2020 and Open Space ones, at times when there are upcoming land purchase possibilities or even for sheer educational purposes. Then, the city could contract a grassroots organizing group if it didn’t have the human resources to contact people, that would flyer, knock on doors, phone call and email citizens about the dates and times of upcoming conservation meetings. To encourage attendance the city could offer small tax breaks. The city could also try to incorporate a relationship with the city schools where the school would target a piece of land nearby to be conserved and then it would be up to the kids to strategize and fundraise how it would be purchased. The city could bring this up at a school committee meeting or PTA (Parent Teacher Association) meeting. No doubt this would require devotion on the part of the city so in order to delegate the work and responsibility the city could provide an internship for a student (Smith student for instance) with this being the goal. College students, especially Government majors, are seasoned unpaid interns because internships are necessary for the development of a resume but hardly ever paid. The city official would presumably have to give only about 20 minutes of time per week to meet with the student. 19 Suggestions for the City of Northampton in Promoting Smart Growth Northampton is a city that has done a fairly good job with sustainable development compared to other cities in the state and in the country. Northampton’s vibrant downtown creates a desirable center where growth is centered and because of this is it is not terribly difficult to entice people to live there. However rising housing costs in downtown have forced people to relocate away from the center where housing is more affordable. The city could actively purchase affordable housing units for people close to town. The housing at Hospital Hill mentioned earlier, is one housing project that has been developed with this intention. The city could also actively use all the tools and bylaws to their fullest to sustainably develop growth. The goals and the accomplishments that the city has made so far in enacting the Open Space and Recreation plan and Vision 2020 are all positively contributing to smart growth and the City should continue to pursue these. The Conservation Commission should continue to purchase as much land as they can to be conserved by the city. Suggestions for Smith College in Promoting Smart Growth in Northampton Smith College has the right by state law to develop wherever it chooses (Feiden 2005). In this way Smith is acting according to smart growth standards in keeping its campus contained and located in downtown Northampton. Smith could encourage its students, particularly education majors, to go into local schools and talk about land sustainability and could take part in the internship I mentioned earlier. Smith already has dorm style living arrangements for its students, which limits sprawl and this should continue. 20 Conclusion and Broader Implications of Smart Growth Smart growth and limiting sprawl is an issue that has implications up and down, inside and out every level of government, business, education, non-governmental organization, the lists goes on and on. Not only that, but this issue is deeply embedded in American culture and has its roots in the establishment of the country by white settlers. Westward expansion has themed and shaped the ideology and practices of this country along with an individualist attitude that gives license to sprawl. Changing a culture and organizational structure of an entire country is no small or easy feat, which is why the first changes must start at a local level. Promoting smart growth and limiting sprawl in one community not only affects the land and people within the borders, but also sets an example for other communities to learn from and follow. Limitations and Further Research There are many avenues and boulevards for this project to continue. Further research could be done in one of many different veins touched upon in this paper. The history and development of sprawl could be analyzed on a national level and then compared to Northampton. The implications on the loss of biodiversity could be further researched with a breakdown of global, national, state and local affects. Sustainability as a concept could be further explored and applied to land development. By this I mean that other sustainable ways of living could be presented that would further limit sprawl such as job location and availability, reduction of consumerism etc. The history and process of developing and instituting new city regulations 21 would have added an interesting element. Ways of involving land developers and contractors into the discussion of smart growth would be an interesting approach. This paper was meant as an overview of what role the City of Northampton plays in sustainable development and as such the focus remained on the city. This was a limitation because it did not give a full picture of all the forces and elements in play when development is considered and this is why there are so many areas that could be researched further. 22 Sources Cited Davidson, Osha Gray, “Dirty Secrets” Mother Jones. Sept/Oct 2003 Ewing, R., J. Kostyack, D. Chen, B. Stein, and M. Ernst. Endangered by Sprawl: How Runaway Development Threatens America’s Wildlife. National Wildlife Federation, Smart Growth America, and NatureServe. Washington, D.C., January 2005. Feiden, Wayne, Director of Planning and Development for Northampton’s Planning Department. Interviewed at 210 Main Street, Room 11 on April 15, 2005 Foundation for Deep Ecology- information found at: http://www.deepecology.org - accessed on April 20, 2005 Hardy, Christopher “Romney’s Rollbacks” Sanctuary. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Winter 2004-2005, p.27. Knox, Robert “‘Smart Growth’ Questionnaire Shaping State Grant Allocations” Boston Globe. February 27, 2005 Massachusetts Audubon Society “Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary”- information found at: http://www.massaudubon.org/Nature_Connection/Sanctuaries/Arcadia/index.php accessed on April 15, 2005 Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs (EOEA) “Connecticut River Valley: City of Northampton”- information found at: http://commpres.env.state.ma.us/community/cmty_main.asp?regionID=conn&regionNam e=Connecticut+River+Valley&communityID=214&communityName=Northampton accessed on March 28, 2005 Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs (EOEA) “Sustainable Development and Urban Environments”- information found at: http://www.mass.gov/envir/sus_dev/default.htm - accessed on March 28, 2005 Massachusetts Office for Commonwealth Development- information found at: http://www.mass.gov/ocd/ - accessed on March 28, 2005 Northampton Conservation Commission- information found at: http://216.20.81.58/WebRoot$/OPD/OPD_WebSite/ConsComm/ - accessed on April 15, 2005 Northampton Office of Planning and Development- information found at: http://www.northamptonplanning.org/ - accessed on March 12, 2005 Northampton Vision 2020. Adopted by the Northampton Planning Board, June 10, 1999. 23 Open Space and Recreation Plan: 2000-2004. Endorsed by the City Council, March 16, 2000. Prugh, Thomas et al., The Local Politics of Global Sustainability, 2000, Island Press: Washington D.C. Skelly, Christopher, Preservation Through Bylaws and Ordinances, Massachusetts Historical Commission, 2003. Suzuki, David, The Sacred Balance Greystone Books, Vancouver, B.C., 1997 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)- information found at: http://www.epa.gov/livability/ - accessed on March 12, 2005 24