Hester Garskovas, Victoria Helms, Mikaela Sanders, Alexis Yoon May 8th, 2012

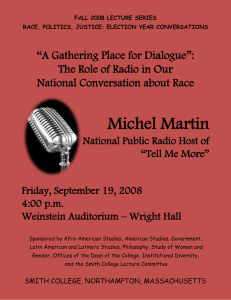

advertisement

Hester Garskovas, Victoria Helms, Mikaela Sanders, Alexis Yoon May 8th, 2012 The Uncertain Future of the MacLeish Field Station Smith College possesses 240 acres at the Ada and Archibald MacLeish Field Station in Whately, Massachusetts, roughly nine miles from the campus in Northampton. The college purchased the land for environmental education and research, but did not establish any form of protection for the property. This decision stems from trust within the college to not take any actions that would compromise the educational uses of the property. However, in this paper we argue that the most important reason to conserve MacLeish is not simply to prevent the property from being sold or developed, but to significantly strengthen the dynamic value and purpose of MacLeish. MacLeish represents an important asset of the college because numerous academic departments, from biology to art, utilize the field station to enhance learning and promote sustainable practices. This carries special weight in today’s society amidst growing concern for our environment. In this regard, the issue has expanded to multiple realms. It is a political issue because it involves authority and power exchanges within social relations. It is an ecological issue because of the impact land fragmentation has on habitat and endangered species conservation. Above all, it is an ethical issue, because it relates to the intrinsic value we place on our natural environment. In this project, we examine how and why this area of land would benefit from a conservation restriction. In addition, we investigate the history of the land, biodiversity and current land use, potential opposition to establishing a conservation restriction, and the effects of land conservation on the Whately and Smith College communities at large in order to establish the optimal strategy to protect MacLeish. We discuss both land conservation and preservation, 1 the definitions of which are not always made clear by outside literature. We have worked with these terms and put together our definitions. Preserving land keeps the area unchanged. Conserving land includes some land preservation as well as carefully using and improving the land by preventing negative changes but allowing restricted use that benefits the natural ecosystems present. Ultimately, granting official protection for MacLeish will not only exemplify Smith’s environmental image, but it is the only way to ensure that the land will remain intact and untarnished in the uncertain future. The History of the Field Station The land that became part of the Smith College MacLeish Field Station in May 2008 has a long and diverse history. The marks left by different types of land use create a unique opportunity to study the area’s history. The historical land use of MacLeish is representative of Western Massachusetts in general. In the 17th century, the area that is now the MacLeish Field Station was part of the town of Hatfield, as Whately only became a town in 1771. During the 1700s, the area was largely covered by old growth forest. Native Americans may have walked through the forests and hunted in the mountains, but they lived in the valleys where the soil is more fertile. They did not have an intensive impact on this particular piece of land. In the 1770s and 1780s, the area became populated by English settlers. The road that is still visible on the property today was a main county road back in the 1770s. It was called a “highway” because it was one of the important north/south roads in the state.1 Revolutionary War soldiers returning from the war settled around this road. There are three known farm sites on and near the property from that time. One of the farms is a house that is still standing and occupied. It is the second house on the road leading to the field station. There is another farm 1 Bellemere, J. (March 12, 2012) Personal Interview 2 site located near a vernal pool. The structure is gone, but there is a visible indent in the land from where the cellar was dug out. The last farmhouse is not on Smith property but is at the top of the hill, and is now also abandoned. Whately families grew larger during these two decades, in accordance with the population boom the entire country was experiencing. A family of eleven occupied one of the now-abandoned farms: a mother, father, and their nine children. The other abandoned farm was home to a reverend, his wife, and their seven children. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, English settlers transformed the land by clearcutting the old growth forest and building stone walls. These previous owners focused on extracting resources from the land. It was a working landscape, and people shifted from simply living off the land to using the land to make a profit. Initially, the land was heavily farmed, plowed, and pastured. However, over the next century, farming on the land became less intense. The pasture was marginally used and the land was no longer plowed. There remained a woodlot where trees were kept for firewood and other uses, and a sugarbush on the land where a group of sugar maple trees were kept for making maple syrup. In the 1880s, the Whately farms were completely abandoned and the land gradually returned back to its former forest habitat. By the 1920s, the forest had grown back significantly. This secondary forest covers the property today and is composed of trees that are one hundred years or younger.2 The land now part of the MacLeish field station is a part of the typical Western Massachusetts landscape. The area has become heavily forested but because the land was broken into family farms, 75% of the forest is privately owned. Small parcels of forest add up to provide public benefits like scenery, clean water and wildlife. The future of the forest relies on many owners of a few acres each. Smith purchased the land from the town of Whately in 1962 to control people from building near the college observatory, fearing it would cause light pollution. In 1975, Smith 2 Bellemere, J. (March 12, 2012) Personal Interview 3 acquired another portion of the property that was donated to the college by Jill Ker Conway.3 These bold actions from the college were not well-accepted by the Whately public. By purchasing the land, 240 acres were taken off of Whately’s tax record, increasing tax rates. Smith claimed exemption from having to pay real estate taxes on the land because the college is technically a charitable nonprofit and the land was occupied for educational purposes. Whately assessors argued that Smith was not using the land for academic reasons, and that they were not entitled to a charitable organization tax break because the college engaged in sex discrimination by virtue of being a women’s institution. The city of Whately sued Smith College in 1981 in a lawsuit entitled “Trustees of Smith College vs. Board Assessors of Whately,” but lost.4 However, the current relationship between Smith and the town of Whately is generally not negative. Smith faculty and staff have volunteered at many Whately organizations such as; The Whately Cable Access Committee, The Whately Cultural Council, The Whately Elementary School, The Whately Land Trust, and the town newsletter, The Scoop.5 Smith maintained its tax-free ownership of the land, and in 2008, the area was officially named the Ada and Archibald MacLeish Field Station after the three-time Pulitzer prize-winning poet and his wife. Today, the town of Whately has a total area of 20.7 square miles. The area of MacLeish is .02% of the total area of Whately. The town is located in Franklin County in Western 3 MacLeish Field Station. Smith Center for the Environment Ecological Design and Sustainability http://www.smith.edu/green/about_macleish.php 4 Trustees of Smith College vs. Board of Assessors of Whately 385 Mass. 767 (1982) http://masscases.com/cases/sjc/385/385mass767.html 5 Volunteer Activity. Smith’s Impact in Northampton http://www.smith.edu/northampton_vol.php 4 Massachusetts, and is part of the Springfield Metropolitan Area. Whately is bordered by Conway, Deerfield, Sunderland, Hatfield, and Williamsburg. Whately has a very small population of about 1,500 individuals, and the town is mainly white (97%). The median income of Whately households is $58,929, and 3% of the population is under the poverty line.6 The land area of the entire town is generally rural and scenic, as the town is located on the western bank of the Connecticut River. It includes secondary forest, swampland, marshland, farmland, and a 980-foot mountain (Mount Esther). The secondary forest habitat in Whately (that composes most of the MacLeish property) is very characteristic of New England and demonstrates the layers of human activities that have occurred there over the past two hundred years. By studying the current physical state of the field station, we can observe how quickly a forest can recover from disturbance. A great deal of research can be done at MacLeish because of its complex land use history. Current Land Use The 240-acre parcel known as MacLeish Field Station (shown in Figure 2), boasts a patchwork of woods, wetlands, and meadows. As one of the state’s largest remaining stretches 6 Whately, Massachusetts Onboard Informatics, Advameg Inc. (2012) http://www.city-data.com/city/WhatelyMassachusetts.html 5 of land that does not contain any buildings for residential or commercial use, rendering it ‘undeveloped’ by conventional market standards, it retains invaluable natural resources and diverse ecosystems. The greatest portion of vegetation is a mixed hardwood forest composed primarily of hemlock, oak, pine, and birch. It provides a home to a wide variety of native species including bobcat, deer, turkey, squirrel and coyotes. Multiple streams run intermittently through the property. Out of the five types of wetland habitats, the vernal pool is regarded to be very unique because of the specialized invertebrate animals and amphibians that depend on it for survival. These seasonal pools are especially vulnerable to human activities such as building and are eligible for state protection under special certification guidelines.7 A crucial component of preserving the rich biodiversity of Massachusetts, the third most densely populated state, is habitat protection. Massachusetts’ Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, classifies a large portion of MacLeish as ‘Priority Habitats of Rare Species.’ Priority Habitat (illustrated by the yellow shaded region in Figure 3) is the geographical extent of habitat for all state- Figure 3. NHESP ‘Biomap’ Source: http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/nhesp listed rare species, both plants and animals, and codified under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. These rare species include salamanders, dragonflies, fish, mussels, plants, and a turtle. The Shortnose Sturgeon (fish) and the Dwarf Wedgemussel (bivalve) have a federal 7 "Vernal Pool Certification." Natural Heritage. Department of Fish and Game. <http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/nhesp/vernal_pools/vernal_pool_cert.htm> 6 status of ‘Endangered.’8 This landscape is critical to ensuring the long-term survival of species of conservation concern, natural communities, and intact ecosystems across the state. Figure 3 also demonstrates that the land encompassing MacLeish has significant natural value, thus providing another crucial incentive to conserve. Those we interviewed that are connected to MacLeish expressed the Figure 4. Protected vs. Unprotected Land Source: Smith College possibility that if Smith were to take the first steps in conserving the land, the adjacent landowners would be more likely to follow suit. Figure 4 reflects how fragmented the land currently remains in terms of protection. The green areas represent protected land and the white areas represent unprotected land, including the red area of MacLeish. To the right of MacLeish is about 600 acres owned by the Department of Fish and Game that cannot be developed because it is owned as a conservation area (the mechanisms of land trust programs are elaborated on towards the end of the paper). To the left is the West Whately Reservoir maintained by the Northampton Water Division, which is 7.7 acres in size and can store 17.6 million gallons of Northampton’s water supply. Northampton has an active land trust acquisition program to secure the land surrounding the West Whately Reservoir and Ryan 8 “The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife).” <http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/nhesp/nhesp.htm> 7 Reservoir in order to keep the town’s drinking water safe from pollution. At its northwestern boundary, the city-owned watershed land abuts the 1,946-acre Conway Forest. Thus, the exemplary natural communities in the area are more likely to remain unharmed and thrive if protected as a whole. There are approximately twenty acres of buildable land in the center of the parcel, which is the location of the new Bechtel Environmental Classroom (BEC). The green area in Figure 5 highlights that which is considered buildable, while the red and orange regions demonstrate steep slopes that will be challenging to develop. The 2300 square-foot classroom and research facility will be built with the stringent codes enforced by the Living Building Challenge. The BEC will have net-zero energy use due to a photovoltaic array that will generate all power used by the building. Artificial lights, equipped with sensors, will be used only when there is insufficient daylight. All Figure 5. Building Constraints Source: Smith College of the materials used in the construction have to be approved by the Living Building Challenge, which excludes the use of mercury, halogenated flame retardants, HCFCs, PVC, and many other common substances in construction projects.9 The Living Building Challenge requires net-zero water and therefore the well on site pulls water from renewable aquifers recharged by 9 The Living Building Challenge Standards https://ilbi.org/lbc/LBC%20Documents/LBC2-0.pdf 8 precipitation and the building’s greywater system. The composting toilets utilized in the plan are also low in water use. Part of the Living Building Challenge is to put into protection the same amount of land that was disturbed by the construction. The field station is in no way limited to the use of natural sciences and many departments utilize the resources that the station has to offer. Originally purchased for use by the astronomy department in the 1970s, the existing observatory is rarely used anymore due to the encroaching light pollution, an irony given one of the initial reasons for obtaining the land. Upcoming plans for improvement include clearing areas around the observatory to further improve the capabilities of this resource. In recent years, Plant Ecology (BIO 364) and Statistics (MTH 245) have collaborated to design and implement numerous experiments and observational studies on plant species. The field station also acts as a “creative” stimulus for dance classes (DAN 521: Choreography and the Creative Process) and an “inspiring”10 canvas for architecture and landscape studies (LSS 250: Landscape and Narrative). Students in the Environmental Science and Policy Class (ENV 201) have the opportunity to directly apply the techniques and information gained in class to surveys and experiments conducted at the field station. Other departments include Geology and Engineering. Lastly, Introduction to Archaeology (ARC 135) was able to apply research and analytical skills from the classroom to investigate and reconstruct the past culture of New England through material remains such as stone walls, building foundations, and lead and zinc mines. MacLeish even served as the site of a National Archaeology Day celebration for the AIA Western Massachusetts Society, Whately Historical Society, and students from Smith and Mount Holyoke Colleges11. 10 "Notes From the Field Station: MacLeish as a Classroom." CEEDS. Smith College. <http://smithceeds.wordpress.com/2012/01/27/notes-from-the-field-station-macleish-as-a-classroom-resource/> 11 "MacLeish Field Station." Smith College: Green Smith. Smith College. <http://www.smith.edu/green/macleish_research.php>. 9 Scientific research is an another essential part of what goes on at the field station. Most projects have the objective of protecting the environment through studying the threats of climate change, invasive species, and much more. Professors Drew Guswa, Amy Rhodes, Paul Wetzel, and Jesse Bellemare have worked with students over the summer doing research at MacLeish. One of the large-scale science projects is the planting of 3,000 American/Chinese chestnut tree hybrids. Many of the trees will not live to maturity because of an exotic blight that attacks American chestnut trees, but the hope is that some of the hybrids will possess a blight-resistant gene from the Chinese chestnut.12 The system of trails offers recreational opportunities for all Smith students and community members. Currently, there is no hunting allowed on the property, but snowmobiling is acceptable. As the owner of the land, Smith retains the power to create and enforce rules at the field station. After the building of the Bechtel Environmental Classroom, the field station is expected to receive more use than previous years and attract an even greater variety of departments. No courses will be scheduled there regularly, but any course or student that wishes to engage with nature is welcome to use the classroom.13 There is even a yoga and dance studio. Students are encouraged to use the new amenities, do homework outside, or take a breather from work and simply enjoy the scenery. Potential Opposition to Protecting MacLeish While many proponents of the environmental sciences on campus strongly approve of the idea to conserve a large part of the MacLeish Field Station, there are also others on campus who might question the real need to conserve the land. This doubt stems from the belief that Smith 12 Bertone-Johnson, Reid (2012), Personal Interview Ibid. 13 10 simply trusts itself to not extensively develop or sell the land. The sole reason that Smith purchased the parcel of land was in order to effectively use it for classroom purposes. Smith trusts that any action that would impede these academic purposes would not be allowed. To help make sure that the classroom use of MacLeish is preserved, the first set of guidelines for the use of MacLeish Field Station was recently established. A total of about ten different rules and guidelines for the proper usage of the field station, the simple set of guidelines marks Smith’s desire to control and somewhat restrict activities that occur in the field station. Any action that concerns MacLeish must enhance or protect the educational purpose of the land use.14 The opposition may argue that conserving the land for the sole reason that it would ensure the preservation of the land in its current state is not a pertinent enough reason for many Smith board members or officials. In a case in which it is clear that there is a valid reason to conserve the land (other than to merely protect it from being sold or overly developed), the other great oppositional force lies within the possible constraints on educational uses of the area. For an area that has defined and very predictable uses and purposes, the conservation restrictions can easily circumvent current usage to avoid any constraints. A concrete acreage of land needed for possible development for the sake of educational purposes can also be clearly defined. However, Smith College has hopes that the role of MacLeish at the institution will evolve over the years. In the past decade alone, the station changed from being virtually unused as well as unheard of by Smith students to becoming an active outdoor learning environment for various courses throughout the academic year. While there is worry about possible restrictions to the current usage of the the field station, there is also further worry about constraints on any future plans and land uses that have yet to occur. Creating conservation restrictions now can prevent flexibility in future field station usage. 14 Constantine, Ruth (April 5, 2012), Personal Interview 11 Even if Smith decides that the merits of conserving the area outweigh the negatives, there are further difficulties in determining exactly how much land can be conserved without harming the flexibility of academic usage. The oppositional side of this proposal may also wonder, how important is conserving MacLeish in establishing further environmental leadership at Smith? It is clear that Smith has already taken initiative in providing ample opportunities for environmentally-interested women on campus. The news of conserving MacLeish, some may argue, will only temporarily grab attention from the local community and the five-college system. The conservation state of MacLeish is not exactly a concern that many people would wonder about without first being interested in or aware of the topic. In the perspective of many Smith officials, the best case scenario for the MacLeish Field Station would be the absence of potential restriction for classroom use in both the present and the future. Those who oppose the conservation of MacLeish may feel that if an action might possibly be regretted in the future, near or far, that it is perhaps best not to commit to that action. However, these arguments opposing conservation err on the side of absolute safety and no risk, which is almost impossible when dealing with a collegiate institution that strives to be groundbreaking and innovative. Benefits of Protecting MacLeish Field Station After analyzing the pros and cons of protecting MacLeish, we concluded that it would be worthwhile to protect 90% of the land under a conservation restriction. If 90% (216 acres) of MacLeish was conserved, 10% (24 acres) would be left unprotected to provide Smith the option of constructing more classrooms or a student cabin in the future. There are multiple rewards to 12 protecting the land. Officially protecting 90% of MacLeish would improve Smith’s environmental leadership role in the five-college community, prevent land fragmentation, conserve endangered species and habitats, and inspire local landowners to protect their own land. College Hall is trying to market Smith as a place for environmentally-interested women to come study, and protecting the land would help position Smith in a place of environmental consciousness. Since Smith has already moved forward to build a station there for the purposes of environmental education, protecting 90% would be a number that would resonate with the Smith community and cement the college’s status as a conservation-minded place to study. If only 24 acres remains protected after the Living Building Challenge is completed, the public may wonder: What does Smith plan to do with the rest of the land? Establishing a conservation restriction for MacLeish would not only do a great deal for Smith’s environmental image, but would also put Smith students at an unique position to lead conservation efforts of the Pioneer Valley region. By taking the initiative to protect their land, Smith might inspire nearby landowners to protect their own land. The more land that is conserved, the less that the habitat is in danger of fragmentation. As Environmental Science and Policy majors, we know that large blocks of continuous protected land is best for species conservation, and the current fragmented protection situation is not ideal. MacLeish is home to many species in need of protection, including bear, moose, bobcat, coyote, wild turkey, spotted salamander, and various endangered snakes.15 Vernal pools are tiny intricate ecosystems that require specific environmental conditions to remain habitable, and MacLeish’s hemlock forests are starting to feel the effects of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid pest. Conserving the land would insure that the vernal pools remain and are not 15 “The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife)” http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/nhesp/nhesp.htm 13 impeded by development, and it could also provide more environmental study and management of the adelgid pest for the hemlocks. Land conservation restrictions often include mandatory soil and water tests, and this data could further improve the sustainability of MacLeish. The immediate neighbors within a half mile of MacLeish seem to feel very positively about conservation. The Wildlife Management area near MacLeish includes 200 acres that the owners had wanted to sell to developers, but MacLeish neighbors arranged for it to be purchased by the state of Massachusetts (a conservation restriction facilitated through the Franklin Land Trust). This being said, relations between Smith College and the town of Whately have not always been positive. Smith took 240 acres of their land off their tax record and did not give them any financial compensation for use of the land in their town. 16 Thus, if Smith ever began making money off the MacLeish property, there could be legal problems. The town of Whately sued Smith over the land in the 1980s, and it could happen again. Smith could go a long way to defending its educational use of the field station by putting 90% of the land under protection. The Process of Conserving MacLeish If Smith College decided to officially conserve MacLeish Field Station, it would need to work with a land trust. Land trusts are models of conservation that originated in Massachusetts one hundred years ago. Conserving land through a land trust is different than conserving it federally. Land trusts take a free market approach to conservation. Rather than using the legal system to conserve land, they use the market. This appeals to a larger spectrum of landowners, because while many people may feel emotionally attached to their land, most want some compensation for conserving it. Land trusts can provide them with either tax deductions or an 16 Trustees of Smith College vs. Board of Assessors of Whately 385 Mass. 767 (1982) http://masscases.com/cases/sjc/385/385mass767.html 14 actual payment for the whole property or a portion of it. Land trusts work by purchasing the development rights from the landowner. The overall cost is calculated by subtracting its undeveloped worth from how much it could be worth if developed to its maximum potential. Any parcel of land comes with its own set of rights, including the right to farm, forest, build, or hunt. A land trust would buy these development rights, and then work with the landowner to create a conservation restriction. The main land trust in the Pioneer Valley is Kestrel Land Trust. There are at least five other land trusts in the area as well as public conservation agencies like the Department of Fish and Game and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation.17 Kestrel is based in Amherst, making facilitation easier between the two organizations. The choice to use Kestrel was both political and convenient. This particular land trust has worked with the Northampton Department of Public Works, which gives it more leverage in the area. A neighbor had proposed using Franklin Land Trust to conserve the MacLeish property in the past, but Smith College officials decided it was unnecessary at the time since Smith was planning to use the land for solely educational purposes. Using Kestrel shows that Smith is approaching land conservation on its own. Kestrel is the best choice for Smith because the land trust is particularly understanding about recreational use. It is flexible about the amount of trails that can be built, while Franklin would have required a map of all the trails to be built in the future. The hiking trails at MacLeish will certainly evolve with use over the years. Because recreational use is one of the ways the field station can be used to inspire students, Kestrel is the land trust that best fits with Smith’s mission for the field station. Smith is already working with Kestrel to conserve the 17 Contact Information for Resources in Whately. MassWoods Forest Conservation Program (2009) http://masswoods.net/contacts/339-whately 15 24 acres required by the Living Building Challenge. Therefore, it makes sense for Smith to continue working with Kestrel to create a conservation restriction for MacLeish Field Station. Conservation restrictions are legal documents that specify how a parcel of land can and cannot be used. It includes restrictions on how much land can be developed and if land can be used for forestry or agriculture. Every state has a different conservation restriction format. Massachusetts includes state oversight of the land. In some states, land trusts are the sole holders of the conservation restriction, but in Massachusetts, these documents must be signed off on by the executive secretary of environmental affairs in Boston, the landowner, and the municipality. Kestrel Land Trust would work with Smith to decide exactly what the MacLeish conservation restriction should involve.18 They will examine what the 240 acres are currently providing in terms of natural resources for water quality, endangered species, viewsheds, and recreational purposes. Each one of these attributes is assessed and spelled out in the conservation restriction. Conservation restrictions are very flexible and can be tailored towards particular uses. Some are more stringent, like the “Forever Wild” restriction that allows nothing at all to disturb the land. Others can be specifically tailored towards agriculture, forestry, or watersheds. At the same time that the conservation restriction is created, a baseline report is drafted. The baseline report is a summary of the property, including its acreage, GPS values, who its landowners are, conservation values identified in the conservation restriction, disturbed areas of the land, dumping on the land, and current agricultural usage. The baseline report also includes photos and maps that display areas of important natural resources. According to Kristin DeBoer, the head of Kestrel Land Trust, a conservation restriction for MacLeish would prevent no new buildings or barns from being created, but agriculture and 18 Interview with Kristin DeBoer, executive director of the Kestrel Land Trust (2012) 16 forestry would be allowed (with parameters).19 While land trusts provide the option of financial compensation for conservation, Smith could not receive financial benefits because the college is considered a charitable non-profit, so the land could not be taken off its tax record. The step-by-step process of conserving MacLeish Field Station would be as follows: 1) Negotiation phase: Starts with initial site visit, meeting with landowner (which would be Smith), includes a conversation about what MacLeish means to the college and reasons for conserving the land. 2) Appraisal phase: Investigating potential tax benefits of conserving the land (there would not be any for the college, as it is considered a charitable non-profit). 3) Conservation restriction/Baseline report 4) Closing phase: Real estate closing, facilitated by an attorney on both sides. Grantor: Smith College, grantee: Kestrel Land Trust. 5) Long-term stewardship begins: Annual obligation, forever. While a lifetime commitment to conservation may seem daunting and restrictive, we believe that it is the only way to establish permanent protection for the fragile habitats of MacLeish. An official conservation restriction with Kestrel Land Trust will ensure that Smith remains forever dedicated to environmental protection, and environmental courses in the college’s curriculum will maintain a long tradition of benefiting from the presence of a conserved field station. Reflecting on our Potential Biases 19 DeBoer, Kristen (March 9, 2012), Personal Interview 17 As we contemplated this project, we recognized just how biased we are as Environmental Science & Policy majors. We initially met with Reid Bertone-Johnson, a Landscape Studies lecturer at Smith and the manager of the MacLeish Field Station, to discuss the details of our research project. Berton-Johnson immediately stated his support for the 90% conservation plan for the field station, citing the benefits it would provide the college, species retention, and towngown relations. We initially took his strong opinion as uncontested truth, and did not consider the fact that as manager of the station, Bertone-Johnson is likely to have more specific goals for the land than most people. Our education as Environmental Science & Policy majors has included many classes about the importance of species conservation, the detrimental effects of land fragmentation, and the vast harms caused by globalization and urbanization. Thus, it is not surprising that we instantly agreed with Bertone-Johnson - what reason could there be to not conserve land? A few weeks later, we forced ourselves to step back and consider our biases (and Bertone-Johnson’s). While our motivations as environmentally-minded students are not necessarily wrong, they are not universal truths. By talking to Ruth Constantine, the Vice President of Finance and Administration at Smith College, we were able to analyze more objectively what the meaning and the importance of conserving MacLeish would be to Smith. We were also able to figure into the equation the administrative perspective of making decisions at Smith. Right from the start of our interview, Constantine made it very clear that all decisions made at Smith should be based on protecting or enhancing the educational mission of Smith College. Certain reasons like establishing Smith’s leadership role in environmental issues as well as conserving for the (sake of conserving), did not seem like they were strong enough to immediately persuade college officials, like Constantine, to decide to conserve the land. However, it seemed that she, as well as other interested parties at Smith such as the Building and 18 Grounds Committee, would be easily convinced if the argument was made that enhancing and protecting the land would be the same as enhancing and protecting the educational uses of MacLeish. While we were still convinced, after talking to Constantine, that 90% of MacLeish should be conserved, we were able to see how some of the reasons for conservation that were very much valid to us may not be seen as favorably by others at Smith. Conclusion Although the idea of conserving MacLeish was originally born from environmentallyminded professors and staff at Smith, the conservation of the field station goes far beyond simply making a statement of sustainability to the public. By conserving the land and ensuring the prevention of fragmentation, Smith is effectively helping to preserve the natural ecosystems of the field station as well as potentially enhancing the area. Currently Smith is acting as a responsible steward of the land by focusing on its educational purposes, but the next step is to decide what the future of the land will be. As Aldo Leopold writes in A Sand County Almanac, “It is inconceivable to me that an ethical relation to land can exist without love, respect, and admiration for land and a high regard for its value. By value, I of course mean something far broader than mere economic value; I mean value in the philosophical sense.” The value of the land is tied to the benefits it has for the college as an opportunity for research and recreation. A love of nature can begin at any age, and thus all students should have the opportunity to experience a different landscape than the manicured botanic gardens on campus. Experiencing nature leads to greater understanding and compassion for non-human life on earth. A liberal arts education is not complete without some experience of the natural world. 19 The impact of climate change is also an important part of the reason that MacLeish should be conserved. Over the next few decades, the ecosystems of Western Massachusetts are very likely to suffer effects of climate change. Having a protected field station available to take consistent environmental data from will undoubtedly be a boon for the college’s science departments. While conserving endangered species and habitats is very worthwhile and one of the main goals of this project, the potential for Smith to increase its capacity to be an environmental leader should not be overlooked, especially because it could persuade neighbors to take similar actions. Conserving 90% of MacLeish Field Station does not reflect an arbitrary decision, but a calculated endeavor to inspire Whately neighbors and other colleges to follow in Smith’s footsteps and conserve their own land. Work Cited Interviews: - Interview with Jesse Bellemare, biology professor at Smith - Interview with Kristin DeBoer, executive director of the Kestrel Land Trust (3/9) - Interview with Reid Bertone-Johnson, manager of MacLeish (2/17) - Interview with Ruth Constantine, Smith’s vice president of finance and administration (4/6) Online Sources: - “Biological Field Stations” http://www.obfs.org - “Massachusetts Land Trust Coalition” http://www.massland.org/ - “Kestrel Land Trust” http://kestreltrust.org/ - “Massachusetts General Laws: Chapter 61A” 20 http://www.malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleIX/Chapter61A - “Massachusetts General Laws: Chapter 61B” http://www.malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleIX/Chapter61B - “MacLeish Field Station on AIRMAP: Mapping New England’s Climate and Air Quality” http://airmap.unh.edu/data/data.html?site=AIRMAPWH - “The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife)” http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/nhesp/nhesp.htm - “Smith Plans Environmental Ed Center at Whately Site” http://www.gazettenet.com/2010/09/30/smith-plans-environmental-ed-center-whatelysite?SESS7acfb5a2f8434f00632dd37ebd79aecb=gnews - “Whately, Conway: Franklin County Chamber of Commerce” http://www.franklincc.org/whately.html, http://www.franklincc.org/conway.html - The Living Building Challenge Standards https://ilbi.org/lbc/LBC%20Documents/LBC2-0.pdf - “Trustees of Smith College vs. Board Assessors of Whately.” http://masscases.com/cases/sjc/385/385mass767.html - “Whately, Massachusetts” http://www.city-data.com/city/Whately-Massachusetts.html - “MacLeish Field Station. Smith Center for the Environment Ecological Design and Sustainability” http://www.smith.edu/green/about_macleish.php - “Volunteer Activity. Smith’s Impact in Northampton” http://www.smith.edu/northampton_vol.php - “Contact Information for Resources in Whately. MassWoods Forest Conservation Program” (2009) http://masswoods.net/contacts/339-whately Literature: - The Massachusetts Conservation Restriction Handbook - Taxpayer’s Guide to Classification and Taxation in Massaschusetts - ABA Journal: Feb 1982, “Smith College Tax Case Questions Exempt Status” - Golodetz, A. D. and Foster, D. R. (1997), History and Importance of Land Use and Protection in the North Quabbin Region of Massachusetts (USA). Conservation Biology, 11: 227–235. 21