Depth In W Perspectives in Social Work

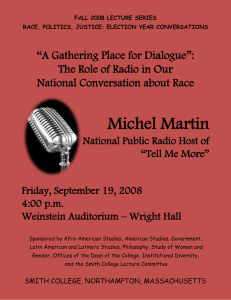

advertisement