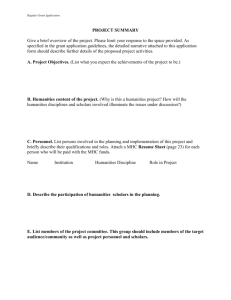

The LAIRAH Project: Humanities Final Report to the

advertisement