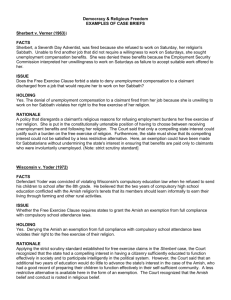

RETHINKING FREE EXERCISE OF SMITH AND BOERNE:

advertisement