Document 12884635

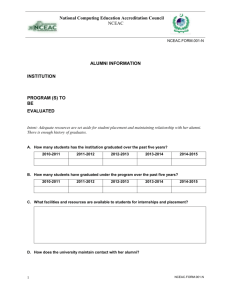

advertisement

Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Volume 2, Number 1, February 2012, pp. 3-22 Evidences of Learning: The Department Profile Gary L. Kramer, Coral Hanson, Nancy Wentworth, Eric Jenson, Danny Olsen Brigham Young University Facing growing accountability pressures, many universities and colleges are looking for ways not only to address institutional accountability for learning but also to sustain purposeful assessments over a period of time. In this paper, we present the Department Profile model and apply it to the Teacher Education Department at Brigham Young University (BYU). The Department Profile engages stakeholders to align, gather, analyze and summarize data around eight components: (a) Current Year Graduate Profile; (b) Department Learning Outcomes & Evidence; (c) Five Year Graduate Longitudinal Profile; (d) Senior Survey; (e) Employer Survey; (f) Alumni Survey; (g) National Survey on Student Engagement (NSSE); and (h) Department-Appropriate Accreditation Table. The Department Profile was developed and refined through three questions: (a) What key data sources that are sustainable evidences of learning should comprise the Department Profile? (b) Through the process of stakeholder engagement, what data are most important to college and department leaders, and should be incorporated in the Department Profile? and (c) As a result of telling the data story through the Department Profile, what issues or concerns should be addressed by faculty and department leaders as they seek to demonstrate program value, and what program and student performance areas give cause for celebration? Actual implementation of the Department Profile demonstrated that it does usefully summarize evidences of learning strategies and outcomes, providing both direct and indirect measures, of what are working well and what improvements need to be made to enhance student learning and development. This paper addresses key issues, concepts, and principles relevant to advancing accountability and continuous improvement via a department profile that highlights student learning and development. The department profile brings together data essential for faculty and department leaders to apply their leadership in making data-based adjustments in program and course development. Clearly, data alone cannot determine decisions. People make decisions, but key data ought to inform the decisions made. The Department Profile model described in this study provides department leaders and faculty with critical data on student characteristics and feedback on important issues, such as (a) In what areas has the department Correspondence: been dramatically better over the past five years as a result of assessment data analysis and reporting? (b) What is the department data story for both recent graduates and longitudinally—what is the program narrative? and (c) What are the areas of assessment that matter most, as empirically demonstrated in aligning institutional/departmental claims (learner outcomes) with evidence for student learning and development? (Kramer & Swing, 2010). This paper addresses documentation of student learning and student engagement as a means to establish a culture of assessment and evidence, particularly in putting students first or giving voice to students in the learning enterprise. Thus the premise of this paper Gary L. Kramer, CITES Department and Professor of Counseling Psychology and Special Education, David O. McKay School of Education, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602. E-mail: gary_kramer@byu.edu Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Volume 2, Number 1, February 2012, 3-22 4 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation is to connect and explore foundational pillars of programmatic assessment. The Department Profile concept is a cooperative study between Brigham Young University’s (BYU) office of Institutional Assessment and Analysis and the McKay School of Education. Specifically, the Department Profile model described in this study was successfully implemented in the Department of Teacher Education (BYU). The research study and application model demonstrates the following pillars of a culture of evidence. • • Adopting rigorous standards to create an assessment infrastructure, one that measures what is of value to accreditation assessors, faculty grant writers, and other constituents. Using a data systems approach including intentional and specifically tailored assessment tools that are aligned with institutional claims and enable a demonstrable culture of evidence. (Kramer & Swing, 2010) Background for the Development of the Department Profile Model The Department Profile was developed out of a philosophy of program assessment congruent with the following set of principles. • • • • • Access and query essential information (data) on student progress, development, and learning in a timely way. Determine whether the program and student learner outcomes have been achieved—what is working and where improvements need to be made. Ensure that assessment tools are intentional (purposeful)—aligned with and able to qualitatively measure department claims. Use an established culture of evidence to tell the data story to various constituencies—both inside and outside the institution—including faculty, department chairs, college deans, accreditation agencies, and potential employers. Engage stakeholders to discern what matters most to them in a department profile. (Kramer, Hanson, & Olsen, 2010) As Smith and Barclay (2010) stated, student learning assessment is not easy, and it requires significant time, thought, and resource investment if it is to be done correctly. It also requires careful consideration of how best to tap into and enhance the motivation and intrinsic needs of faculty members, staff members, and students for pursuing this work. When such challenges are ignored, externally-imposed accountability approaches will ultimately neglect developing intentional assessment strategies aimed at understanding the phenomena by which learning emerges. In taking this path of seemingly less resistance, the institution will have created less rigorous research designs and less useful instruction and program designs, inadvertently undermining its ability to document and present valid evidence of learning. Key Considerations for Documenting Learning Via Assessment Activities As an institution or individual department proceeds to establish a plan to document student learning, some of the questions to be asked include the following: • • • • • • • What is the theoretical or disciplinary rationale behind desired proficiencies, and is this clearly articulated and aligned at the program or course levels? Are rationales for intervention and instruction clearly articulated and linked to desired learning outcomes for programs, services, and courses? Are the outcomes related to facilitating cognitive engagement precisely clarified (i.e., metacognition, learning approaches, attitudes, motivation, etc.)? What are the modes for facilitating learning, and how do they support the overall design philosophy for instruction and assessment as well as documentation needs at the institution and program levels? Is the full set of learning goals covered by the proposed set of assessments? To what degree of specificity are the unique characteristics of the population factored into collection, instruction, and analysis? Do baselines and post measures map onto desired outcomes for (a) specific content knowledge; (b) transferable strategic knowledge (content neutral); and (c) motivation, self-efficacy, attitudinal, and cognitive and metacognitive skills? The Department Profile 5 • • At the program and campus levels, who are the individuals or offices charged with the actual implementation and documentation strategies, ongoing review of design fidelity, and incorporation of fidelity review into relevant formative and summative analyses? Who is responsible for ensuring technology is available and adapted, and how is it resourced to meet the initiative’s facilitative and documentation requirements? (Carver, 2006, p. 207) The research literature (e.g., Banta, Jones, & Black, 2009) provides a plethora of ways to document learning, especially through electronic portfolios and program review profiles. The Association of American Colleges and Universities’ VALUE (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education) project is another example of measuring student learning based on institutional success in the use of e-portfolios, particularly in measuring essential learning outcomes such as critical and creative thinking, written and oral communication, and literacy (Cambridge, Cambridge, & Yancey, 2009; Rhodes, 2009). But what is different about our teacher education (i.e. special, elementary and secondary education) Department Profile is its focus on annually providing methodology and strategies to unlock, as well as to connect, essential data sets stored at the institutional, college, and department level. Just as important are the needs to outline key issues and benchmarks for learner success and to summarize in the Department Profile essential data components of student learning, performance, and success. Every department might choose a somewhat different mix of components for their own Department Profile as it should be tailored to its needs and situation. The specific Profile developed for the Department of Teacher Education in BYU’s School of Education, shown in detail later in the article, documents learning via charts, narratives, and graphs for each of the following profile components. • Current Graduating Class Profile (number of students graduated; major GPA; cumulative GPA; high school GPA; percentage of females and males graduated; ACT/SAT composite scores; grade frequency distribution for foundation, practicum, and student teaching/internship courses; number of students placed; and percentage of students passing PRAXIS). • • • • • • • Department Learning Outcomes Analysis (e.g., data analysis from assessment tools aligned with department learner outcomes). NSSE (National Survey on Student Engagement) (e.g., comparative data analysis of faculty-student interaction and student interaction with campus culture/environment for each teacher education department). Employer survey highlights (e.g., school of education and specific department tailored surveys). Alumni survey highlights (e.g., school of education and specific department tailored surveys). Senior survey highlights (e.g., school of education and specific department tailored surveys). Department longitudinal data for the past five years (e.g., application, retention, and graduation rates; state placement rates; major and cumulative GPAs; grade frequency distribution for foundation, practicum, and student teaching/internship courses). Accreditation data table (key data required by TEAC/NCATE). The Department Profile differs from the academic program review and/or learning portfolios as discussed by Banta and Associates (2002), Cambridge et al. (2009), Seldin and Miller (2009), Suskie (2009), and Zubizarreta (2009), but it is nonetheless a compilation of key data from diverse assessment tools which are organized to tell the department data story: for example, evidences of learning strategies and outcomes. Overall, the questions the profile seeks to answer through its analyses of these various assessment tools are “How did students perform?” and “What endorsements are there for program strengths as well as needs for program improvement?” The intent is to capture growth from student program entry through graduation. It supports the demonstration and valid assessment of student progress and academic capabilities. Assessment Systems Approach It can be a daunting endeavor to establish sustainable processes of intentional assessments, analysis and reporting to adequately profile any degree program let alone substantiate the extent to which its learning goals are being met. Having an established 6 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation systems approach can be helpful. Such an approach could include a number of inherent strategies and perspectives to represent varying dimensions, depending on the institution and the specific program or degree being profiled. Alignment and Focus Ideally the strategy employed to profile a particular degree complements parallel processes at the department, school, college, and institutional level. Such alignments will facilitate complementary utilization of effort and result in satisfying varying demands for specialized and regional accreditation as well as institutional accountability. Linkage needs to be established to facilitate the required roll-up of information along the continuum of objectives from the course level to the program level through the institutional level. Pragmatics of implementation require effective planning and coordination to successfully integrate optimal data from multiple sources. Available data may come from institutional surveys or databases as well as from individual courses or other areas that transcend the student experience. To avoid duplication of effort and labor, all should become aware of the landscape of available and emerging resources across campus that could help substantiate the degree to which learning objectives are being met. All data sets that can be disaggregated at the program and degree level are potentially applicable. The focus should be the students. Contrary to varying attitudes that may exist in higher education, the principal reason institutions of higher education exist is for the students. They are the customers, patrons, and clients—everything should contribute to their learning. And there are many parts of the institution which affects students. Everyone on campus should in some way or another share accountability in an institution’s assessment strategy focused toward improvement. Academic units as well as educational support units (e.g., bookstore, library, housing, employment, student life, etc.) contribute to students’ university experiences, their subsequent learning, and their perceived return on their educational investment. This accountabilty demands evidence of learning or evidence of improved learning. Tools Direct and Indirect Assessments Academic departments that systematically utilize direct and indirect assessement tools with students are well equipped to adequately demonstrate student learning. Direct evidence might include facultydeveloped proficiency evaluations, writing assessments, departmental competency exams, or even external performance-based standard exams in varying areas such as critical thinking. Indirect (self-report) evidence can be derived from institutional instruments such as surveys of exiting seniors, alumni, employers of graduates, etc. The direct tools measure what is being learned by focusing on kernel concepts of the discipline, proficiency in each of the technical courses, communication skills that cross course boundaries, and critical thinking. The indirect tools provide supporting data on learning specifics, but also focus on how and why learning is taking place. The effectiveness of learning activities, the degree of student engagement, and the impact of various aspects of the learning environment are effectively investigated with these tools. Strategies for evidences of learning should include both direct and indirect evidence. Evidence strategies are strengthened as they move beyond attitudes and perceptions of learning to include performance-based data. External Data Beyond internal data, benchmark comparisons that result from institutional participation in national surveys are an important part of any strategic assessment plan, as they provide external context for the data. Thus each program should examine the comparative content of available surveys and determine which would yield data best suited to their mission, goals, and objectives. Pertinent data may be mined from existing or emerging data sets resulting from institutional participation in national surveys. As external data are available and feasible, they enhance assessment strategies. Assessment strategies that triangulate from many data sources, whether internal, external, direct, or indirect, enhance success in telling the data story specific to student learning. However, determining the appropriate mix of assessment plan components requires a cost/benefit analysis of existing and potential resources and their perceived contribution to the process. Program level assessment strategy frame- The Department Profile 7 works need to be intentional and sustainable and by design, with the capacity to complement the applicable demands of internal university review as well as specialized and regional accreditation. • Stakeholder Engagement • Without stakeholders’ engagement to ownership, especially that of teacher education department leaders, the Department Profile would be an act of futility with little chance of success as a useful report. We have found it particularly effective to actively engage stakeholders in at least two ways: (a) in the design, look, and feel of the profile, and (b) in identifying, reviewing, and approving the data used to populate the profile. In soliciting engagement, organizers must identify the most essential data required for grant writing and accreditation review. They must also ask overall what concisely tells the data story of students graduating from their program in order to create a profile that can be shared with other academic units and leaders, including school districts. The Department Profile should be a win-win development. A sustainable assessment and analysis report relies on stakeholders’ collaboration in designing, delivering, and using the data from assessment. The literature suggests many strategies to use in engaging these individuals and groups. The following general strategies have been used successfully to engage stakeholders in this project. Each strategy can be effective regardless of the population from which the stakeholders originate. • • • • • Representation: All stakeholders should be represented and feel they have a “voice” in developing the Department Profile. Responsibility: All stakeholders should be given the responsibility to provide feedback and approve the report. Conversation: Developing and sustaining the profile report (planning, executing, and using results) must involve a conversation including all stakeholders. Unified purpose: Stakeholders should view themselves as teammates, united to improve student learning and development and to tell the data story for their department. Intrinsic motivation and rewards: Stakeholders should be motivated to participate in the developing the student profile for reasons beyond the requirement of doing so. • • Patience: Successfully engaging stakeholders at the level needed to effectively sustain the report will take time. Expectations: Realistic expectations and reasonable timelines must be set. Technical support: Necessary technical support must be provided, along with substantive report drafts for review. Efficiency: Development and use of the Department Profile should be linked to the program self-study and planning processes that are already in place. A sustainable system of assessment and reporting will begin to emerge as stakeholders are engaged and given responsibility in assessing and reporting data. Thus assessment is more likely to be “ongoing and not episodic” as engaged stakeholders assume active roles in the development of the report (Angelo, 2007, 1999; Banta & Associates, 2002; Banta, Jones, & Black, 2009; Daft, 2008; Huba & Freed, 2000; Kramer & Swing, 2010; Kuh & Banta, 2000; Maki, 2004; Miller, 2007; Palomba & Banta, 1999; Wehlburg, 2008). Applying the Department Profile Model to the BYU Department of Teacher Education This next section presents a specific Department Profile developed for the BYU, David O. McKay School of Education, Department of Teacher Education. The development of this Department Profile was a joint effort including the data analysis team and other departments across campus that will also use the data. Process Data collection and analysis began with the need to meet accreditation standards. Although teacher candidates from this institution have high market value, there was little consistent evidence of the impact of teacher preparation programs in advancing their knowledge, skills, and dispositions as teachers. Program goals and outcomes were assessed with input measures such as course syllabi and instructor qualifications. But accreditation agencies were moving toward outcome measure such as observational data and performance assessment of our teacher education 8 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation candidates. We needed to show how we were using data to measure candidate performance and program efficacy as well how we were using the data to improve the program. A data analysis team was created to identify the structures for collecting, analyzing, and reporting data. Initially data analysis was complicated because results were housed in many different files. The data team began to organize the data and create data reports by semester and academic year for department leaders and faculty. The tables were often complex, and the graphs were not always organized in ways that the department leadership found useful in finding patterns in program outcomes. The data analysis team continually asked for feedback on the nature and dissemination of reports. Soon the reports were in a format that provided useful information to department leaders. After many iterations, a consistent Department Profile has been defined that reports data in tables and charts by semester and academic year. The systematic collection of data from multiple sources provided essential information for planning and decision making. Wide dissemination of the Department Profile to leaders and faculty is generating ownership of program changes and unit improvements. Components The Department Profile consistently includes several components that support accreditation and other faculty activities including grant writing and research. • The executive summary highlights strengths and weaknesses in the program--information which is useful for accreditation reports. • The yearly graduate profile of students provides demographic data concerning graduates that can be extremely valuable to the faculty when applying for grants. • The accreditation page provides data needed to show how teacher candidates are meeting program learning outcomes. • The longitudinal profile provides invaluable evidence of growth of candidates during their time in the program. • The survey data from seniors and alumni help with long-term development of our program because we learn what was and was not of value to our graduates. • Employers’ survey results help us understand the long-term impact of the candidates as they move into the workplace. • The National Survey on Student Engagement (NSSE) includes classroom experience, types of class work, enrichment activities, academic engagement, and overall satisfaction. All of these common pages have been jointly developed by the data analysis team, the department leadership and faculty, and additional groups across campus that also use the data. Data collection and analysis began with the need for data evidence to meet accreditation requirements, but has moved beyond its originating necessity to benefit department faculty, students, and administrators in a wide range of significant ways. Example: The Department of Teacher Education’s Department Profile Extensive data were collected for the Department Profile, and many times multiple samples and sources were used for each component of the profile. The following sections first detail data sources for each component and then describe sampling and analyses conducted for each section. Profile Components 2009-2010 Graduating Students The 2009-2010 graduating student component, shown in Figure 1, was developed to provide an academic summary of seniors who graduated during the most recent academic year. Data points for this component were selected for multiple reasons: use by departments as evidence for their learning outcomes, use in accreditation reports, use by faculty in specific reports such as grants, and other uses for which certain data points should be available. The sample used for the 2009-2010 graduate profile included all graduates of the BYU McKay School of Education from the December 2009 and April 2010 graduating classes. All students from this group were included in the sample due to small populations in the majority of the programs. Data were obtained from the university database (AIM), the ESS database in the School of Education (which houses student academic information specific to the teacher education programs that could not be found on AIM), and the State of Utah CACTUS The Department Profile 9 report (which reports on all teacher education graduates who are placed in full-time teaching positions in Utah). The following data points make up the 2009-2010 graduating student profile: number of students graduated, major and cumulative GPA of graduated students, percentage of female and male students graduated, frequency distribution of graduating students’ grades for important courses (foundation course, practicum, and student teaching), number of graduating students placed in full-time teaching positions in Utah, and percentage of graduating students who passed PRAXIS. Analyses of the 20092010 graduating student component consisted of means, percentages, and frequency distributions. The 2005-2010 Longitudinal Student Profile The 2005-2010 longitudinal student component, shown in Figure 2, was developed to provide retention statistics along with an academic summary of graduates from the past five years. This component consists of a summary of the following data points from the last five years: (a) number of students graduated, (b) major and cumulative GPA of the graduates, (c) frequency distribution of graduated students’ grades from core courses (foundation course, practicum, and student teaching), (d) number of graduated students placed in full-time teaching positions, (e) percentage of male and female students, and (f) percentage of graduating students who passed PRAXIS. The longitudinal component also includes application and retention rates from the last five years. The samples used for the 2005-2010 Longitudinal Profile page included (a) all students who applied to teacher education program 2005 and 2010, and (b) all students who graduated from teacher education between 2005 and 2010. The first sample of students who applied to the teacher education programs was obtained to calculate retention rates, and the second sample provided the five-year academic summary of graduates. Data for the first sample were obtained through the ESS School of Education database and AIM. The ESS database was used to obtain the list of students who had applied to teacher education in the last five years. AIM was used to track when students left the program or graduated. Data for the second sample were obtained from AIM, the ESS database, and the State CACTUS report. AIM provided the list of students who had graduated from teacher education between 2005 and 2010 and their academic information. The ESS database provided information regarding students’ scores on the PRAXIS tests, and the CACTUS report detailed whether or not each student had been placed in a full-time teaching job in Utah. Analyses for this component of the profile consisted of frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations. Department Learning Outcomes and Evidence The component of department learning outcomes and evidence, as shown in Figure 3, consists of the department’s learning outcomes with corresponding direct evidence displayed in chart form. Each teacher education program lists its learning outcomes and specifies the related direct and indirect evidence (whether it be a course or certain section from an assessment) on the university’s learning outcomes website (learningoutcomes.byu.edu, which displays each department’s learner outcomes and related evidence). This component utilizes data from the core assessments administered to students at specific points throughout the program: e.g. at the time of application, during student’s practicum experience, and during the student teaching/internship experience. The data also include PRAXIS and major GPA data. The sample of students used includes all student teachers from the Fall 2009 and Winter 2010 semesters. Analyses of the direct evidence for the learning outcomes components consist of means and standard deviations. Results were displayed in chart form based on feedback from stakeholders on ease of reading. Accreditation Data Table The accreditation data table consists of statistics from core assessments, PRAXIS, and major GPA of student teachers from the current academic year in a presentation format patterned after tables required for yearly accreditation reports. This piece includes data from core assessments administered to all student teachers during the Fall 2009 and Winter 2010 semesters. It also includes PRAXIS and major GPA data from this same group of students. Analyses of the data for the accreditation table consist of means and standard deviations of the core assessment data. Table 1 provides a sample of this component. Surveys Three surveys (employers, seniors, and alumni) were created in collaboration with the university’s Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, which 10 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation provided expert guidance in creating valid survey instruments. By building their own unique surveys, the Department of Teacher Education was able to align survey questions to specific departmental learning outcomes. Previously the department had used a national third party instrument to survey their graduates, alumni, and employers of alumni. The thirdparty survey did provide for multiple customized questions, but it was not sufficient to allow alignment of all department learning outcomes stakeholders wanted to measure. Once again, stakeholders throughout the department were engaged in constructing the surveys. The surveys went through several iterations before being approved by the Dean. Senior survey. The senior survey component is a summary of the survey sent to all graduating students for the current academic year (see Figure 4). The survey consisted of multiple Likert-type questions aligned to Teacher Education Department learning outcomes along with several open-ended questions about program improvements. The population used for the sample of the senior survey included all graduates of the BYU McKay School of Education teacher education programs from the December 2009 and April 2010 graduating classes. All seniors were included due to small numbers in multiple programs. Seniors were emailed a letter inviting their participation and providing a link to the survey. They were sent two reminders about the survey after the initial invitation. All teacher education programs distributed the survey via email except elementary education. Seniors in elementary education were given a hard copy of the survey by one of their professors during class and were asked to complete it on their own time and turn it in to the department. Analyses of the data for the senior survey consisted of frequency distributions, means and standard deviations, and qualitative analysis of the open-ended responses. Alumni survey. The alumni survey component, as shown in Figure 5, summarizes the survey that was sent to all alumni who had been students from the previous academic year (2008-2009). It consisted of multiple Likert-type questions aligned to Teacher Education Department learning outcomes that asked alumni to rate how well they felt the program had prepared them in these areas to be an effective teacher. Several openended questions were included at the end of the survey as well. The population used for the sample of the alumni survey included all graduates of the BYU McKay School of Education teacher education programs from August 2008 to April 2009. All alumni were included due to small numbers in multiple programs, in an attempt to increase the likelihood of a return rate adequate to ensure meaningful results. Alumni were emailed a letter inviting their participation along with a link to the survey. They were sent two reminders about the survey after the initial invitation. Analyses of the data for the alumni survey consisted of frequency distributions, means and standard deviations, along with qualitative analysis of the open-ended responses. Employer survey. Figure 6 shows the employer survey component, a summary of the survey that was sent to a sample of principals of alumni who had graduated during the last three academic years (20062009). The survey consisted of multiple Likert-type questions aligned to Teacher Education Department learning outcomes and asked principals to rate how well they felt their teachers who were BYU alumni incorporated these areas effectively in their teaching. Several open-ended questions were included at the end of the survey. The population used for the sample included employers of all graduates of the BYU McKay School of Education from April 2006 to April 2009 who were employed full time as teachers in the State of Utah. The State of Utah CACTUS report was used to identify these graduates and associate them with their principals. Graduates from this population were linked back to their program focus at BYU. When program groups were identified, a random sample of graduates was taken from elementary education (1-8) and secondary education (6-12) due to the size of the populations; the other groups were simply added to the sample. Then the number of graduates for each principal was calculated. Principals who employed more than five graduates selected for the study were identified, and graduates from elementary education and secondary education were randomly removed to reduce the overall count per principal to five or fewer graduates. Principals of graduates selected to be part of the survey were sent a letter introducing them to the survey and explaining that they might receive multiple survey invitations--one for each of the graduates selected to be part of the survey. A week after receiving this email, reminder emails after receiving the first invitation to participate. The Department Profile Figure 1 09-10 Graduating Student Profile Page 11 12 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Figure 2 2005-2010 Longitudinal Profile The Department Profile Figure 3 Department Learning Outcomes Page 13 14 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Table 1 Accreditation Data Table Fall 2009 Winter 2010 CPAS Principle 5: Learning Environment and Management n=94 4.20 (.68) n=316 4.47 (.63) CPAS Principle 6: Communication 4.31 (.69) 4.49 (.61) Enculturation for Democracy as assessed by CPAS 5, 6 Access to Knowledge as assessed by CPAS 1, 3; TWS 1, 5, 6; CDS 3; Praxis II; Major GPA CPAS 1: Content Knowledge 4.23 (.71) 4.61 (.58) CPAS Principle 3: Diversity 3.80 (.74) 4.03 (.64) TWS 1: Contextual Factors n=47 1.77 (.25) n=158 1.79 (.29) TWS 5: Instructional Decision Making 1.82 (.37) 1.81 (.37) TWS 6: Analysis of Student Learning 1.82 (.24) 1.81 (.26) CDS 3: Diversity n=50 4.33 (.46) n=160 4.22 (.45) Praxis II Exam: 14 n=46 150 176.74 (12.33) 100% Exam: 14 n=156 150 177.17 (12.46) 99% n=47 3.70 (.20) n=161 3.75 (.20) Passing Score Mean St Dev % Passing Major GPA Nurturing Pedagogy as assessed by CPAS 2, 7, 8; TWS 2, 3, 4; CDS 1 CPAS 2: Learning and Development 4.19 (.69) 4.45 (.60) CPAS 4: Instructional Strategies 4.22 (.62) 4.56 (.59) CPAS 7: Planning 4.39 (.59) 4.57 (.59) CPAS 8: Assessment 4.03 (.66) 4.24 (.65) TWS 2: Learning Goals and Objectives 1.85 (.18) 1.84 (.24) TWS 3: Assessment Plan 1.71 (.25) 1.69 (.30) TWS 4: Design for Instruction 1.75 (.23) 1.73 (.29) The Department Profile Figure 4 Senior Survey 15 16 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Figure 5 Alumni Survey The Department Profile Figure 6 Employer Survey 17 18 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Figure 7 NSSE Survey The Department Profile 19 principals received additional invitations, each with the name of a graduate bolded. Principals were sent two Analyses of the data for the employer survey consisted of frequency distributions, means and standard deviations, and qualitative analysis of the open-ended responses. By linking the graduates with their current principals, this research obtained data directly from the immediate supervisors of the graduates. These direct data provide a better view of students’ performance post-graduation than previous employer surveys, many of which had asked supervisors to rate their impressions of the graduates of the university without identifying which individuals had worked with the supervisor. NSSE (National Survey of Student Engagement) The National Survey of Student Engagement component (see Figure 7) consists of data from a nationwide survey in which BYU participates. For the year 2010, all BYU graduating seniors had been requested to complete the survey, which includes classroom experience, types of class work, enrichment activities, academic engagement, and overall satisfaction. An invitation to participate in the national survey was sent to all seniors who, based on their total number of credits, appeared likely to graduate following the 2010 academic year. As the invitation was sent to all seniors, results from the survey could be provided for most academic departments and programs on campus, including the teacher education programs. The first invitation was sent by the NSSE researchers in early February 2010. Those not completing the survey were sent up to four subsequent reminders. At the completion of the data collection phase, 53% of the BYU seniors had completed the survey. Participation in the NSSE survey allows BYU to benchmark the BYU results with those of several preselected national groups. In addition to the university level report, BYU’s office of Institutional Assessment and Analysis used the provided data to create customized reports for programs on campus which had large response sizes. These customized reports provide comparisons between individual programs and their national program counterparts, all Carnegie peer results, and BYU as a whole. The national program counterpart comparison data were created by matching Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes of 85 program level groupings done by the national organization with the program CIP codes of BYU programs. The analyses consisted of frequency distributions, means, standard deviations, significance testing, and effect sizes. Findings Overall, the findings from the Department Profile were highly positive concerning the students, faculty, and programs. The Department Profile is now valued for the aid it provides all department faculty in making important decisions about program improvement and meeting accountability requirements. The Department Profile has helped create a unified vision throughout the Department of Teacher Education, and individual faculty members are beginning to accept the new datadriven paradigm. Areas of strength and areas for improvement were both revealed by the profiling process. A key factor in identifying these areas was being able to triangulate the data through multiple sources which were all aligned to department learning outcomes, yielding similar results across several different assessments. For example, the survey data showed that an area in which graduating seniors and alumni did not feel as well prepared, and principals also rated as observing less frequently in student teaching, was adapting instruction to diverse learners. This area was also measured on the core assessments, and graduating seniors received lower ratings from their professors in adapting instruction to diverse learners on these assessments as well. In summary, multiple assessments showed that BYU teacher candidates needed more instruction and guidance in this area. An area of strength in this same program that yielded more positive results across the surveys and core assessments was students’ professionalism and preparation to become reflective practitioners. Areas of strength and needed improvements across programs were also revealed. One such area was the high retention rate across elementary education, special education, and early childhood education. All three programs had retention-to-graduation rates of 85% or higher. This sort of triangulation of data from multiple aligned sources provides more meaningful results, leading to more certain conclusions that programs are excelling or need improvements in certain areas. Throughout the process of engaging stakeholders concerning these data, we found this engagement enhanced the conversation about data in the department 20 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation and helped us establish more accountability towards the department using the data for program changes and improvements. For example, special education stakeholders met with the data team on several occasions to customize their profile pages with data that would be most useful to them. Several of their requests focused on data needs for different grants that stakeholders write annually. In addition, stakeholders wanted to include data they had just started collecting regarding practicum experiences. One of the leaders of another program distributed copies of the entire profile to the program faculty and held a specific meeting to discuss these data and consider ways the data would be used to enhance the program. Initiating these conversations with faculty in the process of developing the profile made it particularly meaningful for the department program leaders as well as creating a feeling of ownership of the profile among them. In summary, some of the most useful findings from the development and planning of the profile included the following: • • • • Multiple data sources should be used, aligned to the programs’ learner outcomes in creating a Department Profile. The ability to triangulate data around learning outcomes provides much richer and more meaningful results for stakeholders. Engaging stakeholders in the process of designing and implementing (selecting data to collect, creating instruments, etc.) creates a sense of ownership and accountability for using the data to enhance the program. Stakeholders should be encouraged to dig deeper and be willing to look at additional analyses; results may look positive overall and differences between low and high ratings may not seem important, but further investigation may be needed to determine if the area is one that does need to be addressed in program improvements. Conclusion We close this article by emphasizing the collaboration, cooperation, and collegiality among department, college and university assessment personnel as they worked together and integrated their data sources, which comprised the essence of the Department Profile. This culture of evidence was critical to the success of the project. Without it, student burnout might have occurred, along with inadequate cooperation in completing assessment surveys from a variety of offices, potentially leading to a low return rate as well as inaccurate and meaningless data. From our perspective as authors and researchers, stratified random methodology along with timing and other selective methods are essential, and without supportive cooperation, especially from BYU’s office of Institutional Assessment and Analysis these important aspects might not have been achieved. Coordination, engagement and timeliness are important in minimizing the number of surveys students are normally asked to complete and critical to successfully delivering a Department Profile. Another important conclusion of our study is that assessments must be intentional—purposeful—and what matters most with data is telling a meaningful data story; one that is aligned with institutional and department claims. When this is accomplished, a database culture can be established for both accreditation and research grant writing purposes. Intentional assessments can also enable celebration of the data story. Efforts must be both systematic and proportionate. As John Rosenberg (2009), Dean of BYU’s College of Humanities, stated in addressing a group of education leaders, “Systematic refers to the arduous process [as well as timing] of gathering and converting information to knowledge by organizing it according to categories we accept as useful”— measuring what we value and informing decisions from what we measure. But “systematic is balanced by proportionate,” which suggests wisdom and balance, not overloading participants with assessment tools that may cause frustration and confusion. Yet “proportionate” has a sense of urgency to it. The key is to balance both; to drive home the point of a culture of evidence and then to celebrate successes. Finally, the researchers have made a conscious effort to ensure that the assessment results are not only meaningful but salient for a range of stakeholders with diverse interests and agendas and that they are disaggregated for underrepresented populations. We claim no magic bullets, only engaged inquiry leading to ownership not only of the processes but of the actual data. The data should be shared openly in the processes of planning, analyzing and reporting. Intentionality matters as much or more than any other factor of assessment. To improve and maximize student learning and development—the central theme of this article— we remind researchers, scholars, and practitioners that assessment of the student educational experience ought The Department Profile 21 to be purposeful, integrated, and most of all focused on what matters most to the students. What better way is there to determine whether the institutional and departmental claims have been met rather than through a mutually approved Department Profile completed annually to ensure updates and reflect changes in and needs of departmental programs? References Angelo, T. A. (2007, November 6). Can we fatten a hog just by weighing it? Using program review to improve course design, teaching effectiveness, and learning outcomes. Materials for a concurrent workshop in the 2007 Assessment Institute, Indianapolis, IN. Angelo, T. A. (1999, May). Doing assessment as if learning matters most. AAHE Bulletin. Retrieved from http://assessment.uconn.edu/docs/resources/ARTICLE S_and_REPORTS/ Thomas_Angelo_Doing_Assessment_As_If_Learning_ Matters_Most.pdf Banta, T. W., & Associates. (2002). Building a scholarship of assessment. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass. Banta, T. W., Jones, E. A., & Black, K. E. (2009). Designing effective assessment: Principles and profiles of good practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Cambridge, D., Cambridge, B., & Yancey, K. (2009). Electronic portfolios 2.0 emergent research on implementation and impact. Sterling, VA: Stylus Carver, S. (2006). Assessing for deep understanding. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning science, (pp. 205-221). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Daft, R. L. (2008). The leadership experience (4th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson. Huba, M. E., & Freed, J. E. (2000). Learnercentered assessment on college campuses: Shifting the focus from teaching to learning. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Kramer, G., & Swing, R. (2010). Preface. In G. L. Kramer & R. L. Swing (Eds.), Assessments in higher education: Leadership matters (pp. xvii-xix). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. Kramer, G., Hanson, C., & Olsen, D. (2010) Assessment frameworks that can make a difference in achieving institutional outcomes. In G. L. Kramer & R. L. Swing (Eds.), Assessments in higher education: Leadership matters (pp. 27-58). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. Kuh, G. D., & Banta, T. W. (2000). Faculty-student affairs collaboration on assessment: Lessons from the field. About Campus, 4(6), 4-11. Maki, P. (2004). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Herndon, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC. Miller, B. A. (2007). Assessing organizational performance in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Palomba, C. A., & Banta, T. W. (1999). Assessment essentials: Planning, implementing, and improving assessment in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Rhodes, T. (2009). The VALUE project overview. Peer Review, 11(1), 4–7. Rosenberg, J. (2009, October). The human conversation. Paper presented at the biannual meeting of the Leadership Associates of the Center for the Improvement of Teacher Education and Schooling (CITES), Midway, UT. Seldin, P., & Miller, E. (2009). The academic portfolio. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Smith, K. H., & Barclay, R. D. (2010). Documenting student learning: Valuing the process. In G. L. Kramer & R. L. Swing (Eds.), Assessments in higher education: Leadership matters (pp. 95-117). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Wehlburg, C. M. (2008). Promoting integrated and transformative assessment: A deeper focus on student learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Zubizarreta, J. (2009). The learning portfolio: Reflective practice for improving student learning. Bolton, MA: Anker. Authors Dr. Gary L. Kramer is Professor of Counseling Psychology and Special Education and Associate Director, in the Center for the Improvement of Teacher Education (CITES) Department, McKay School of Education, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. The author-editor of four books in the past seven years, Kramer’s most recent book is Higher Education Assessments: Leadership Matters, published by Rowman and Littlefield in cooperation with the 22 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation American Council on Education (ACE) Series on Higher Education, October, 2010. Kramer has published 80 refereed journal article in12 different referred journals and delivered over 150 professional papers. Coral Hanson is currently the Assistant Director of Assessment, Analysis, and Reporting for the School of Education at Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. She oversees the assessment data for the School of Education and works with faculty members in reporting and understanding their data. She is the co-author of An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Instructional Methods Used With a Student Response System at a Large University, and co-author of the paper The Pursuit of Increased Learning: Coalescing Learning Strategies at a Large Research University. Hanson completed her Master’s Degree in Instructional Psychology and Technology. Dr. Nancy Wentworth, Chair of the Department of Teacher Education and former Associate Dean of the McKay School of Education, has been a professor in the teacher education department of Brigham Young University for the past nineteen years. She has promoted technology integration in K-12 and teacher education instruction as director of the Brigham Young University Preparing Tomorrow’s Teachers to Use Technology (PT3) grant and the HP Technology for Teaching grant. Dr. Eric Jenson is Associate Director of Institutional Assessment and Analysis at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. Prior to coming to BYU, Jensen was a psychometrician for a test publishing company specializing in IT certifications. Eric completed a Ph.D. in Psychology with an emphasis in research and evaluation methodologies at Utah State University (2001). He has also earned a Master's Degree in Social Work from New Mexico State University. Dr. Jenson is a member of the Association for Institutional Research and the American Educational Research Association. Dr. Danny Olsen is Director of Institutional Assessment and Analysis at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. Dr. Olsen completed a Ph.D. in Instructional Science from BYU with emphasis in research, measurement, and evaluation. Olsen is responsible for developing and implementing an institutional assessment plan that reflects a dynamic school structure, while continuing to integrate various aspects of the planning process. He is the author of several publications and has presented over 40 presentations, including papers at national and international assessment conferences.