INSURING CONSUMPTION AND HAPPINESS THROUGH RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS

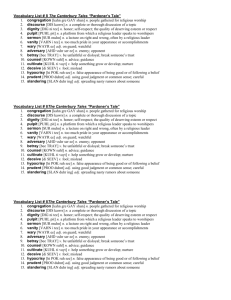

advertisement