The Role of Community Technology Centers in Youth Skill-Building and Empowerment

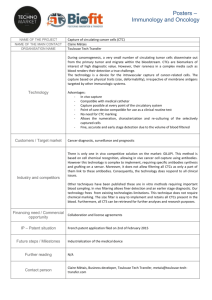

advertisement