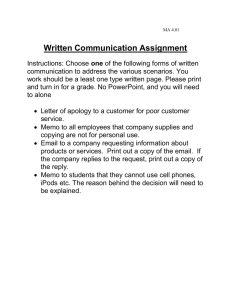

LEGAL The Second Draft

advertisement