& PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS

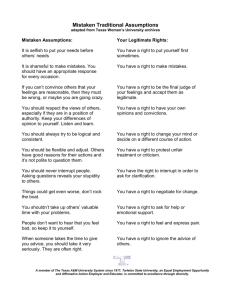

advertisement

PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS FRANK RENE LOPEZ· SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 41 II. HISTORY 43 III. STATISTICAL DATA 49 IV. SOCIAL SCIENCE 56 V. CRITICAL LEGAL ANALYSIS AND RACE THEORy 62 VI. CONCLUSION 64 Associate Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law; J.D., Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California, Berkeley, 1990; B.B.A., The University of Texas at Austin, 1984. I would like to thank the following individuals for their valuable research assistance: Ariya McGrew (Texas Tech, J.D. expected 2005), Adrian de la Rosa (Texas Tech, J.D. expected 2005), and Enrique Martinez (Texas Tech, J.D. 2003). 39 HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 39 2004 40 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LA W & POLICY HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 40 2004 [Vol. 10:39 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS I. 41 INTRODUCfION In 1998, a friend invited me to observe a law school class discussion on affirmative action. At that point in my academic career, I had taught a number of undergraduate courses that included affirmative action as a sub-topic. I walked into the class with the objective of learning yet another way to approach a complex subject. Prior to the class meeting, the students had been assigned to read Regents of the University of California v. Bakke! and Hopwood v. Texas. 2 The class discussion began with the professor asking a few open-ended questions, such as, "Is affirmative action fair?" A lively discussion followed. As expected, one group argued that affirmative action was fair and the other argued that it was not. Most of the discussion centered on individual students' personal opinions. Although the discussion was entertaining, it appeared to be more of a "talk show" discussion than an intellectual conversation based on facts. I walked away thinking about the dynamics in the classroom, especially when the topic of discussion involves race. I immediately began to analyze my own courses. Were students truly understanding the subject matter? It is always instructive to observe a class discussion as a third party observer and not as a student or teacher it provides the observer with a different perspective on the learning process. If an academic discussion is reduced to a "talk show" discussion where the hour is spent sharing opinions, then at the end of the hour no one has learned anything of substance. It is tantamount to going to the local mall (or meeting place) and having a conversation with a hundred people about affirmative action. At the end of the discussion, all have shared their opinion, but no one has learned anything new. Some people will inevitably believe that affirmative action is fair and others will not. By observing that one class as a silent observer, I saw how easy it is to derail a strong academic course into a "talk show." Law school by its very nature has the potential of engaging students in healthy discussions on race and diversity. Besides topics such as affirmative action, where a discussion on race and racism is essential, there are many other subjects that could easily include material on race, discrimination, and/or racial healing. For example, each of the following law courses could benefit from such material: constitutional law, education law, criminal law, sports law, employment law, property law, immigration law, and various courses on jurisprudence. 1. 2. Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (5th Cir. 1996). HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 41 2004 42 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 But engaging in a discussion involving race requires more than simply reading a few case opinions. Reading Bakke, Hopwood, or even Grutter v. Bollingel is simply not enough. Understanding the connection between race and law requires a much more thorough and comprehensive study. It is far too easy to fall back on personal experiences, which are not empirically quantified, and engage in an incomplete and biased exchange of opinions-a talk show discussion. In teaching Race & Racism the last three years, it has become apparent that many students lack the background in history and sociology to fully understand some of the topics discussed. People rarely recognize how they have been conditioned to see the world. There is always a number of students who believe that racism no longer exists and that it is a thing of the past. They often base their beliefs on their personal experiences; many students of color, on the other hand, do believe that racism still exists at some level; and, of course, there are always those students who believe it does not matter. To enhance the learning process in courses that involve race, instructors should consider the following four components: (1) history, (2) statistical data, (3) social science, and (4) critical analysis on how the law is shaped. Each of the four components adds a critical dimension to the course. Failure to consider all four components when discussing subjects involving race and discrimination will result in an interesting, but incomplete, discussion. From the inception of this great country, racism has played a significant role in affecting American life. Only a thorough examination of these four elements will provide the necessary foundation. The four components are like the four wheels on a car: if all four wheels are working properly, the car will move forward; if one of the wheels is flat, the car will not move very far; and if one wheel is completely removed, the car will not move at all. This article will discuss the use of these four components. Although I believe that all four components can be applied to a variety of subjects, I will use the topic of affirmative action in the academic setting to illustrate the importance of examining each requirement. Part II of this paper will discuss the importance of history in analyzing the connection between race and law. An accurate picture of history provides the building blocks necessary for appreciating diversity and the programs that promote a multicultural society. Part III will discuss the importance of using statistical data to visualize the status of people of color in education and other settings. Statistics-especially in the form of a chart or graphliterally paint a picture of facts that may otherwise be difficult to understand. Part IV explores the role social science research can play in legal analysis. Without using social science, it is far too easy for people to fall back on their personal experiences, which usually does not represent a complete picture of reality. In the case of affirmative action, the value of diversity and its impact on education is now recognized as a compelling state interest, 3. Grutter v. Bollinger, 123 S. Ct. 2325 (2003). HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 42 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LA W: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 43 largely because of social science research. The Grutter case provides an excellent example on the use of social science in law. 4 Part V discusses the need for critical analysis on how the law is shaped. Most, if not all, courses engage in legal analysis. Few courses, however, consider the forces that shape law, such as the personal bias of key players in the judicial process. Finally, Part VI provides a few concluding thoughts. II. HISTORY There is an old adage in Spanish that goes like this: El pueblo que pierde su memoria, pierde su destino. The adage could be interpreted as follows: "If we do not know where we are from, we do not know where we are going." History is important for many reasons, the least of which is that we learn from the mistakes of the past. For example, we study World War II and the Holocaust so that our children will never allow such horrific things to happen again. The Holocaust is one chapter in world history that no one wants to repeat. Our educational system includes courses on history because it is considered a fundamental component of a well-rounded education. Moreover, history helps us ground ourselves in our past and define who we are as Americans. As Professor Herbert Aptheker once said, "History certainly teaches us, if it teaches anything at all, that human beings have the glorious urge to be something better than they are at any moment, or to do something new, or to provide their offspring with greater advantages and a happier world than they themselves possess."s History provides us with the foundation to better understand contemporary problems. In fact, it is essential. "If we do not know where we are from, we do not know where we are going.,,6 There is a tendency to ignore certain aspects of history. Yet, if one is to understand topics such as affirmative action, one must explore the historical background from which such programs should be considered. 7 Although some students argue that we should be 4. Grutter, 123 S. Ct. 2325 5. HERBERT APTHEKER, ESSAYS IN THE HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN NEGRO 8 (1945). 6. One critical aspect of personal history includes identity and family history. Understanding labels, such as Latino, Chicano, Mexican-American, and Hispanic, are all part of discovering the past and establishing a future. LatCrit scholars examine the issue of identity because it matters if one is to build a promising future. 7. "[I]t is only by delving into the historical forms and implications of race and racism that we may excavate the ideological demons that undergird contemporary racial discord and social ordering." DERRICK BELL, RACE, RACISM AND AMERICAN LAW 1 (4th ed. 2000). See also HOWARD ZINN, A PEOPLE'S HISTORY OFTHE UNITED STATES: 1492PRESENT (Cynthia Merman & Roslyn Zinn eds., Twentieth Anniversary ed. 1999); A LEON HIGGINBOTHAM, JR., IN THE MATTER OF COLOR (1980); RACE AND RACES: CASES AND RESOURCES FOR A MULTIRACIAL AMERICA (Juan F. Perea et al. eds., 2000) [hereinafter Perea]; RODOLFO ACUNA, OCCUPIED AMERICA: A HISTORY OF CHICANOS (Robert Miller & Lauren Shafer eds., 3d ed. 1988); NATHANIEL WEYL & WILLIAM MARINA, AMERICAN STATESMEN ON SLAVERY AND THE NEGRO (1971); WINTHROP D. JORDAN, WHITE OVER BLACK (1968); PAUL FINKELMAN, SLAVERY AND THE FOUNDERS: RACE AND LIBERTY IN THE AGE OF JEFFERSON (1996). HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 43 2004 44 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 "forward-looking" and should not look to the past,S the history that leads up to affirmative action is important. It is essential if one is to understand why affirmative action programs were developed in the first place. Some might attempt to sum up the history of affirmative action in only a few words. For example, it could be said that affirmative action programs began in the late 1960s after President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.9 The idea behind affirmative action was to level the playing field so that people of color, primarily African-Americans, would have the educational opportunities that had previously been denied to them. lO Moreover, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 came at the heels of a tremendous struggle for civil rights fought by activists of all colors who demanded equality in education, in the workplace, in public facilities, and in life. l1 But to limit the history of affirmative action to such simplified statements would fail to present an accurate picture of why affirmative action programs came to be. To have a productive discussion on affirmative action, it is imperative that the course include various historical events involving race that have played a role in shaping life in 12 America. For example, it is significant to remind students that the first African slaves were 8. In the early part of the Fall 2002 Semester, a student in my Race & Racism course once commented, "Why are we blaming dead white men?" He believed that there was no value in studying the history of racism in America and wanted to "be forward-looking." The course was designed to begin with history and conclude with racial healing and solutions on the future of the country. See also BELL, supra note 7, at xxi (challenging the idea that racism is a thing of the past). The phrase "affirmative action" first appeared in President Kennedy's 1961 Executive Order establishing the 9. President's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. Exec. Order No. 10,925,26 Fed. Reg. 1977 (Mar. 6, 1961). The Executive Order currently in force is 11,246, signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, which required federal ,?ontractors to take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated fairly during employment without regard, to their race, creed, color, or national origin. Exec. Order No. 11,246,30 Fed. Reg. 12,319 (Sept. 24, 1965), available at http://usinfo.state.gov/usa/civilri!ihts/laws.htm. President Lyndon B. Johnson is often credited as the president that promoted affirmative action programs. The following is an excerpt from Johnson's address at Howard University: "You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, 'you are free to compete with all the others,' and still justly believe you have been completely fair. Thus it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates. This is the next and more profound stage of the battle for civil rights. We seek not just freedom but opportunity-not just legal equity but human ability-not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and as a result." President Lyndon B. Johnson, Remarks at Howard University (June 4, 1965), reprinted in THE MOYNIHAN REPORT AND THE POLITICS OF CONTROVERSY 126 (Lee Rainwater & William Yancy eds., 1967). 10. See WILLIAM G. BOWEN & DEREK BOK, THE SHAPE OF THE RIVER, 1-14 (1998) (a short history of affirmative action). See BELL, supra note 7, at 666-67. 11. 12. See ZINN supra note 7; BELL supra note 7; HIGGINBOTHAM supra note 7; Perea supra note 7; ACUNA supra note 7; WEYL & MARINA supra note 7; JORDAN supra note 7; FINKELMAN supra note 7. See also Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Horace Greeley (Aug. 22, 1862) available at http://speaker.house.gov/library/texts/lincoln/greeley.asp; U.S. CONST. art. I, § 2, cl. 3; U.S. CONST. art. I, § 9, cl. 1; U.S. CONST. art. IV, § 2, cl. 3; Westminster Sch. Dist. of Orange HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 44 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 45 brought to the Americas in 1619. 13 From the very beginning, the color of skin affected one's status in America. In those early years, there were both white and black servants, yet black slaves were treated very differently.14 White slaves were called "indentured s_ervants,,15 and had a distinct term of enslavement; black slaves were considered slaves with a permanent term of enslavement. 16 Black slaves had no hope of freedom. From the very beginning of this nation, the color of a person's skin made a difference in relationships and legal systems. As far back as 1700, early settlers drafted laws that treated people of color differently than white Americans. For example, the criminal statutes that provided for nailing a person's ear to a tree were laws specifically written for "Negro[es], Mulatto[s], or Indian[s]."17 Similarly, Native Americans were often referred to as "uncivilized savages" whenever there was an issue of land ownership and possession. ls Yet the most powerful historical example of racism found in either the American political or legal systems is found in the U.S. Constitution. 19 In three separate sections of the Constitution, our forefathers provided for slavery and established the basis for a long-term imbalance between the races. 20 The Constitution provides for taxation of slaves as threefifths of a person,21 and also prohibits Congress from restricting the slave trade for a period of time. 22 Interestingly, the drafters of the Constitution were conspicuous in never referring to slaves as "slaves." Instead, slaves were called "Person[s] held to Service or Labour.,,23 Studying the mindset of the men who founded the country is helpful in understanding where County v. Mendez, 161 F.2d 774 (9th Cir. 1947); Delgado v. Bastrop Indep. Sch. Dist., Civ. No. 388 (W.D. Tex., June 15, 1948). 13. See HIGGINBOTHAM supra note 7, at 20-21; see also ZINN supra note 7, at 23. 14. ZINN, supra note 7, at 23. 15. Id. 16. Id. 17. "... Be it enacted * * * That where any such Negro, Mulatto, or Indian, shall upon due proof made, or pregnant circumstances appearing before any county court within this colony, be found to have given a false testimony, every such offender shall, without further trial, be ordered by the said court to have one ear nailed to the pillory, and there to stand for the space of one hour, and then the said ear to be cut off; and thereafter, the other ear nailed in like manner, and cut off, at the expiration of one other hour; and moreover, to order every such offender thirty-nine lashes, well laid on, on his or her bare back, at the common whipping-post." SLAVE LAWS OF THE STATE OF VA., ch. 4 (May 1923) reprinted in Perea supra note 7, at 108-09. 18. Johnson v. Mcintosh, 21 U.S. 543 at 590 (1823). 19. See U.S. CONST. art. I, § 2, cl. 3; U.S. CONST. art. I, § 9, cl. 1; U.S. CONST. art. IV, § 2, cl. 3. 20. U.S. CONST. art. I, § 2, cl. 3; U.S. CONST. art. I, § 9, cl. 1; U.S. CONST. art. IV, § 2, cl. 3. 21. Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned "by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Serve for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons." U.S. CONST. art. I, § 2, cl. 3. 22. "The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight." U.S. CONST. art. I, § 9, cl. 1. 23. U.S. CONST. art. IV, § 2, cl. 3. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 45 2004 46 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 we come from. In affirmative action discussions, students rarely consider the legacy of slavery and segregation. Yet the legacy of slavery and segregation played a major role in creating the great divide between the races in the United States. 24 When people ask, "How long should affirmative action programs last," they should also ask, "How many years were people of color deprived of an education?" These questions cannot constructively be separated. The study of history is essential. A whole mass of people cannot be deprived of equal access to education for hundreds of years25 without tremendous consequences. The country as a whole suffered-and continues to suffer-for having deprived such a large group of people of an education for such an extended period of time. Failing to educate a significant percentage of the population has resulted in substantial educational and economic 26 disparities. The economic gap between the races has its roots in the educational and economic systems that were put in place years ago. 27 Moreover, when one group was deprived of an opportunity, another group benefited. 28 In the same discussion, it is also important to show that segregation laws did not only apply to African-Americans, but they also applied to Mexicans; Mexican-Americans, Asians, dark-skinned people, and white people who may have looked dark. 29 Segregation affected many people. In schools, segregation meant inadequate physical facilities and a lack of teaching resources for schools teaching students of color. While the degree of inferior facilities varied from school to school, it was not uncommon to lump students of different ages and different grades in one room with one teacher. By placing children of color in schools segregated from white children, society lost the benefits of diversity. Generations of children grew up believing one race was better than the other. Inferior schools for children of color resulted in an inferior education, which put children of color at a disadvantage for much of their lives. Some scholars argue that the negative long-term 24. See MELVIN L. OLIVER & THOMAS M. SHAPIRO, BLACK WEALTHIWHITE WEALTH: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON RACIAL INEQUALITY 33-36 (1997). For 335 years, African-Americans were legally prevented from getting an education. The first slave was 25. brought to the United States in 1619, and segregation was not banned in schools until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954). See generally BELL, supra note 7, at 271-321 (discussing the general effects of public segregation). 26. See OLIVER & SHAPIRO, supra note 24, at 12. 27. See id. at 37-42. 28. Id. 29. Segregation laws were applied to Mexicans and to people who did not look white. See, e.g., Westminster Sch. Dist. of Orange County v. Mendez, 161 F.2d 774 (9th Cir. 1947) (holding that segregating Mexican-American children on the basis of race or ethnicity was unconstitutional); BELL supra note 7, at 272 (citing Chicago R.I. & P. v. Allison, 178 S.W. 401 (1915), in which a white woman was the subject of segregation). See also United States v. Flagler County Sch. Dist., 457 F.2d 1402 (5th Cir. 1972). HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 46 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LA W: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 47 effects of segregation affected people of color for many generations. 30 After numerous court battles, segregation in schools was finally banned in 1954 with the United States Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education. 3! But the Brown decision did not stop segregation in practice. It continued for decades after Brown. 32 Desegregation and school equity cases were fought well into the end of the twentieth century.33 Segregation is only one part of the puzzle. When we consider the groups of people who have been historically excluded from educational and economic opportunities, we realize that the list includes women and people of all colors. Each group has a profound untold history, too long to include in this brief article. The history and struggle of various minority groups includes Mexican-Americans,34 Asian-Americans,35 Native-Americans,36 and women. There are a number of milestone events that could easily be included in a course on race and law. 37 It is well-established that education is the key to greater economic prosperity.38 It is only until this last generation-roughly the last thirty years-that we can say that the gates of educational opportunity have been opened for people of color. However, white America has enjoyed centuries of educational and economic opportunities. Affirmative-action programs were designed to make up for years of discrimination. Without considering the historical roots of racism and its consequences on numerous Americans of color, it is easy to sweep literally hundreds of years of history under the rug and forget what happened. As the old adage suggests, memory loss is harmful-a community that forgets its history loses its destiny. 30. See generally OUVER & SHAPIRO, supra note 24. Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954). 32. See generally RANDALL ROBINSON, THE DEBT: WHAT AMERICA OWES TO BLACKS (2000). 33. See, e.g., Alvarado v. El Paso Indep. Sch. Dist., 445 F.2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971). 34. See generally ACUNA, supra note 7; DENNIS J. BIXLER-MARQUEZ ET AL., CHICANO STUDIES: SURVEY AND ANALYSIS (2d ed. 2001); A READER ON RACE, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND AMERICAN LAW 113-25 (Timothy Davis et al. eds., 2001). 35. See generally Perea, supra note 7; DAVIS, supra note 34; FRANK WU, YELLOW: RACE IN AMERICA BEYOND BLACK AND WHITE (2002); IRIS CHANG, THE CHINESE IN AMERICA: A NARRATIVE HISTORY (2003). 36. See e.g., Johnson, 21 U.S. 543 (1823); Cherokee Nation v. Georgia 30 U.S. 1 (1831). Depending on the course, the following is a list of critical cases and events: Grutter v. Bollinger, 123 S. Ct. 37. 2325 (2003); Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978); Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954); Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.SA83 (1954); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950); Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944); Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896); Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393 (1865); Mendez v. Westminister Sch. Dist. of Orange County, 64 F. Supp. 544 (1946). Events include the following: the Civil War (1861-1865); Thirteenth Amendment (1865) (abolished slavery); Fourteenth Amendment (1868) (equal protection); Fifteenth Amendment (1870) (right to vote regardless of race); the "Jim Crow" era; the Bracero Program (1942-1964); Operation Wetback (1940s); the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the 1996 Immigration Act. OUVER & SHAPIRO, supra note 24, at 12, 196. 38. 31. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 47 2004 48 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURN.AL OF LAW & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 Before discussing affirmative action, a history lesson on this country's discrimination against its minorities may prove beneficial. Looking back at my law school experience and after many conversations with students, I have come to believe that law schools could benefit from a prerequisite course on social justice and history.39 Most history books in grades K through 12 have omitted numerous chapters. of American history-especially the history that pertains to people of color.40 Although college history courses may be more comprehensive than those in high school, they are still far from complete. In a course such as Race & Racism, it is helpful to engage in a few exercises that help students literally "see" things from another person's point of view. I like to use several exercises to show how history education is incomplete and unbalanced. 41 For example, one exercise explores the students' grasp of American history and knowledge of American heroes. 42 In this exercise, students are asked to name three white American heroes, three African-American heroes, and· three Mexican-American heroes. Almost all studentsregardless of color-can name three white American heroes; many can name one or two black heroes; and almost all have 'trouble naming even one Mexican-American hero. Students are then asked if they could write at least one paragraph on each of the white, black, and Mexican-American heroes they just named. Again, most students can write one paragraph on a white hero, but cannot write a full paragraph on a hero of color. 43 The point of the exercise is to show the following: (1) how education in the United States does not include the history of people of color; and (2) how little we (as a people) know about the 39. A discussion of a "law school prerequisite" is reserved for another article. 40. To a great extent, history text books in grades K through 12 have excluded the history of African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Asian-Americans, and Native Americans. People of color who have made great contributions to this country have been omitted from text books. In addition, almost all discussion on American racism has also been omitted. Yet, racism is intricately woven into the fabric of American history and subconsciousness. From the time Europeans began settlements in what is now the United States, racism was a fact of life. 41. One such exercise is as follows: on the first day of class I ask students to playa game and answer five questions where I allow only a few seconds to respond to each question. The questions are: (1) Who was the first female vice-presidential candidate in the United States?; (2) Who was the last African-American presidential candidate?; (3) Who discovered America?; (4) Who invented the light bulb?; and (5) When was the Law School established? The response that I'm looking for is the answer to the third question: "Who discovered America?" Consistently, more than 60% of the students in the course answer, "Christopher Columbus." "Did Christopher Columbus really discover America?" I ask. If I sail to Spain and land on Spain can I claim that I discovered Spain? The point of the exercise is to show how easy it is to embrace a belief that is factually incorrect. Immediately after that exercise, I ask if they believe they would have responded the same way if their history teachers had been Native American. The exercise opens the door for discussion on socialization and education. 42. For purposes of the exercise, a "hero" is defined as a legendary figure or someone admired for her great achievements in the United States. 43. For white heroes, students often name historical legends such as Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Benjamin Franklin; for black heroes, students usually name Martin Luther King, Jr.; other black heroes occasionally named include Thurgood Marshall, Frederick Douglas, and Colin Powell; for Mexican-American heroes, students usually name Cesar Chavez, but have trouble naming any others. It is interesting to note that these responses are made from students who predominantly come from cities in Texas where the population is 47% of color. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 48 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 49 accomplishments of great Americans of color. American history is simply not inclusive of all Americans. Typical American education omits several historical chapters describing American racism and what people of color have contributed to the country. In order to address this flaw in our educational system and its impact on contemporary society, we cannot close our eyes and pretend there is no problem. One can never cover up a deep wound with an adhesive bandage and expect it to heal without the proper care. If we are ever to go beyond racism and achieve racial healing, we must first examine its historical roots. III. STATISTICAL DATA Understanding racism in America is not easy; it is too often controversial, emotional, and complex. A balanced course on Race & Law should include statistical data because it allows the instructor to paint a picture of a situation that may normally be impossible to see.44 For example, one can claim there are many people of color in Texas, but a graph literally paints "a thousand words." See GRAPH 3.1 below: GRAPH 3.1 Population of Texas (Estimated) 70.00%,.--------------_ 60.00%+-::==--~--~-----__i 50.00% 40.00% 30.00% 20.00% 10.00% 0.00% White H1sp..IC Black Source: \Nww.eire. census.gov/popestfestimates. php A popular argument in the affirmative action debate is that affirmative action is no 44. For example, in death penalty cases, statistics show that race plays a significant role in determining who is sentenced to death and who is sentenced to life in prison. Statistically, one can see that capital punishment in the United States is characterized by arbitrariness and racial discrimination. David Bruck, Decisions of Death, THE NEW REPUBLIC, Dec. 12, 1983, available at http://www.sociologyl01.net/sys-tmpl/bdecisionsofdeath(lastvisitedMar.11. 2004). HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 49 2004 50 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LA W & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 longer needed because people of color now enjoy equal access to education. This argument is often based on an individual's personal observations and/or assumptions about diversity at universities and colleges across America. Statistical data on student enrollment helps paint the picture of reality.45 Diversity or lack of diversity in colleges and universities becomes apparent by viewing the demographic numbers of students enrolled. Otherwise, it is far too 46 easy to simply draw conclusions based on personal experience. The idea that affirmative action is no longer needed in Texas is questionable when we take into consideration the number of minority students enrolled at the two flagship universities: The University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University. In 2000, at The University of Texas at Austin, the percentage of Hispanics and African-Americans combined was 17%,47 and at Texas A&M University, the percentage of Hispanics and African-Americans combined was 13%.48 See GRAPHS 3.2, 3.3, and 3.4 on the following pages: 45. In 1998, I took a short seminar on social justice taught by Sister Donna Kustusch at the Tepeyac Institute in El Paso, Texas. In the workshop, she introduced the concept of a "praxis circle" in the analysis of social change. According to Sister Donna, there are four stages to affecting social change: (1) Determine what is real; (2) Analyze the situation; (3) Spiritual reflection; and (4) Engage in action. The first step is to "seek what is real." This can be achieved with social science and statistical data. 46. See generally William C. Kidder, The Struggle for Access From Sweatt to Grutter: A History of African American, Latino and American Indian Law School Admissions, 1950-2000, 19 HARV. BLACKLEITER L.J. 1 (2003). 47. Robert Mayer, Bill Aims to End Use of Legacies in Texas Admissions, DAILY TEXAN, Mar. 21, 2001. 48. Id. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 50 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 51 GRAPH 3.2 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN UNDERGRADUATE ENROLLMENT (BY PERCENTAGE) 70.00% 6 5 : - 2 2 ' % . - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - , 61.66% 60.00% 50.00% nmWhite 40.00% _ _ _ _ _ _---1 30.00% - - - - - - - - - 1 .. .. Hispanic Black 20.00% 10.00% o o 0.00% 1996 2002 Source: www.utexas.edu/academic/oir GRAPH 3.3 TEXAS A&M INCOMING FRESHMAN CLASS 90% 80% o 80% 70% 60% EilWhite 50% .. Hispanic 40% .. Black 30% 20% 10% o 0% 1996 2002 Source:www.theeagie.com/aandmnews/120802minorityrates.htm, www.texastopl0.princeton.edu HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 51 2004 [Vol. 10:39 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLICY 52 GRAPH 3.4 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY STUDENT ENROLLMENT 90%8 .4% 80% -'-"""''--- • 0 81.1% 80.6% 80.2% 79.0% 70% 60% E!I White .. Black .. Hispanic 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Source: www.irim.ttu.edu/ARCHIVE/ENRIFALLETHN.HTM The flagship universities maintain low minority enrollment, while the state's demographic numbers continue to change exponentially. Forty-seven percent of the total population in Texas is of color. Hispanics represent 33% and African-Americans represent 11 % of the total population. It is estimated that by the year 2010, most Texans will be minorities. While the tables above indicate that minority students are not enrolling in colleges and universities, the numbers do not tell us why. Some people argue that the applicant pool is too small. However, the table below shows a significant number of Latino and black students are graduating from high school. Thirty-two percent of the total graduates in Texas are Hispanic and 13% are African-American. Moreover, the number of Hispanic graduates is increasing every year. See GRAPH 3.5 on the following page: HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 52 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 53 GRAPH 3.5 Texas High School Graduates 60.00%......-.:1ror-=:::----------------, 54.38% 53.14% 52.99% 51.53% 50.90% 50.00% 40.00% IillWhite - - - I l!II Hispanic 30.00% III Black 20.00% 10.00% 0.00% 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Source: W\lwv.tea.state.tx.us/perfreportiaeis Does affirmative action make a difference? In 1996, affirmative action was banned in California49 and Texas. 5o Without knowing the actual demographic numbers and percentages any speculation on the effectiveness of affirmative action would be meaningless. We now know that after Proposition 209 was passed in California and after the Hopwood case was decided, the number of minority students enrolled in Texas colleges and universities dropped. In Texas law schools, for example, the number of students of color dropped immediately after Hopwood went into effect. 5! TABLE 3.1 on the following page shows the number of minority students at Texas law schools immediately before and after the Hopwood ban went into effect. 49. 50. 51. Cal. Proposition 209 (1996) (enacted as CAL. CONST. art. I, § 31). th See Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (5 Cir. 1996). See Kidder, supra note 46, at 31-32. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 53 2004 54 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LA W & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 TABLE 3.1 52 SUMMARY OF SURVEY OF TEXAS LAW SCHOOLS: THE RACIAIJETHNIC COMPOSITION OF FIRST YEAR CLASSES Black 96-97 Baylor St. Mary's South Texas SMU Texas Southern Texas Tech Texas Wesleyan U.ofHouston U.ofTexas 0 18 22 161 4 15 11 31 Asian Hispanic 97-98 96-97 0 14 16 6 145 I 12 10 453 4 78 26 66 23 21 32 42 97-98 3 92* 45** 13 57 17 17 31 26**** 96-97 Native American 96-97 97-98 0 I II 5 18*** 6 8 2 6 13 22 4 7 24 30 II 39 97-98 I I 0 I I I I 5 3 8 7 2 3 5 3 Students separately categorized as Hispanic, Mexican-American, and Puerto Rican by St. Mary's have been * combined for purposes of this chart under the heading Hispanic. ** Students separately categorized by South Texas as Hispanic and Puerto Rican have been combined for purposes of this chart as Hispanic. *** Students categorized separately by South Texas as Asian and Indian have been combined for purposes of this chart as Asian. **** Students categorized by The University of Texas as Mexican-American have been listed as Hispanic in this chart. In the Bakke case, the Regents of University of California argued that the school's affirmative action program was necessary to better service under-served communities in California. The court dismissed the argument for lack of support. In states with growing minority populations, such as Texas, the issue of under-served communities is a reality. For example, over one-third of the population in Texas is Latino, and predominantly MexicanAmerican. 54 Over three million Texans live in poverty. Eighty percent of the people in this group do not have access to legal assistance. 55 Given the demographics of the state, and the 52. Lackland H. Bloom, Jr., Hopwood, Bakke and the Future of the Diversity Justification, 29 TEx. TECH L. REV. 1,73 (1998). 53. In 1997, the actual number of African-Americans enrolled dropped to four students; yet the percentage of African-Americans (to white students) dropped to similar percentages of African-Americans in the early 19508. See also Sweat v. Painter, 330 U.S. 629 (1950); BELL, supra note 7. 54. Tex. State Data Ctr. & Office of State Demography, 2000 Census, available at http://txsdc.tamu.edu/download/pdf/txcensus/demoprof/dp_tx_2ooo.pdf. 55. Problems for the poor range from family matters to consumer and landlord/tenant matters. Most attorneys in Texas do not do pro-bono work. James C. Harrington, Lawyers Should Help the Poorest Among us, AUSTIN AM. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 54 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 55 growing population of people of color, especially along the border, it would seem reasonable that law schools in the state would attempt to address this trend by enrolling more minority students. However, the number of minority law students remains low in public law schools across Texas. In fact, in some schools the percentage of minority students is almost always static (i.e., no increase in minority enrollment at all). At Texas Tech University School of Law, for example, the number of minority students has never exceeded 18%. The school averages about 11 %. See Graph 3.6 below: GRAPH 3.6: TIU SCHOOL OF LAW NEW STUDENT ENROLLMENT 100% 90% -,-------------.<~=--------__, -'If><''''-''''---=:--~_ftet,--- 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Source: www.irim.ttu.edu/ARCHIVE/ENRIFALLETHN.HTM The situation becomes even more apparent when we consider the demographics of the State Bar of Texas. Over 87% of all lawyers in Texas are white and only 6% are Hispanic. See Graph 3.7 on the following page: STATESMAN, Jan. 24, 2000, at A9. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 55 2004 56 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 Racial/Ethnic Composition of Texas State Bar Membership-2002 100% , - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - , 90% +-----------"~-=-1 80% - j - - - - - - - - - 70% + - - - - - - - - - - 60% + - - - - - - - - - - 50% + - - - - - - - - - - 40% + - - - - - - - - - - 30% + - - - - - - - - - - 20% - j - - - - - - - - - - ElAmerlcan Indian mOther III Asian III African American rnI Hispanic/Latino 11II Caucasian 10%!~~~~~~=i:ii_ 0% Source; www.texasuar.comjmembersjbuildpractlcejresearchjSBOTREP.PDF While it is easy to conclude that Hispanics are simply not qualified to be lawyers, it is a more accurate statement that Latinos and other minorities are not enrolling in colleges and law schools. People interested in diversity should consider whether this lack of diversity is a problem with unqualified students or a problem with school admissions. 56 In an article entitled, The Struggle for Access from Sweatt to Grutter, William Kidder uses statistical data to show how law schools have constructively segregated people of color over the years. 57 This is particularly apparent in Texas. 58 The affect of this segregation can be seen on the table on page 54. Statistics in the form of charts, graphs or numerical comparisons do in fact paint a picture of what might otherwise go unnoticed. IV. SOCIAL SCIENCE People view the world not as it truly is, but rather as they have been conditioned to see it. It is natural to view the world through the lens of one's own biases and experiences. 56. Immediately after the Hopwood decision, the Texas legislature passed the Texas Ten Percent Plan, which required public universities to admit the top 10% of high school graduates. [The plan allows the top 10% of graduating high school seniors to be admitted to public universities.] Recent studies show, however, that plans such as this one have not produced the diversity that legislators had hoped for. See, e.g., Marta Tienda et a!., CLOSING THE GAP?: Admissions and Enrollment at the Texas Public Flagships Before and After Affirmative Action, 37 (2003), at http://www.texastop10.princeton.edu/publications/tienda012103.pdf. 57. See Kidder, supra note 46. 58. In terms of minority students to white students, Texas Southern (Thurgood Marshall) and St. Mary's School of Law admit a disproportionate number of black and Latino students, while the remaining schools cater to white students. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 56 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHIN<;J RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 57 This tendency obscures one's perception of societal norms. The study of social science unveils reality and helps to overcome the bias of one's own personal interpretation of the world. 59 In the case of affirmative action, for example, a balanced discussion cannot take place without also considering the value ofdiversity, admissions criteria, bias in standardized exams, and the connection between race, education and wealth accumulation. The use of social science to support legal arguments is not new. 60 The first time social science was used in court may have been in 1908 in Muller v. Oregon. 61 The attorney, arguing against oppressive working conditions for women, presented empirical evidence .documenting the negative effects of long workdays.62 Social science had a direct impact on the outcome of the case. Social science was also used in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education. 63 The "doll test" research had an unquestionable effect on the decision. 64 The "doll test" research certainly carried more weight than any precedent at the time. Since those early cases, social science has become well accepted in legal scholarship.65 Since then, social science has been used in numerous cases - ranging from issues involving the death penalty to affirmative action. In the Grutter v. Bollinger case, unlike Bakke-where the parties failed to provide any substantial evidence on discrimination and the benefits of racial diversity in higher education - the court allowed expert testimony that addressed several critical issues. Some of the experts in Grutter presented results from longterm studies on diversity. In the ten years leading up to the Grutter decision, a number of studies were published on diversity that certainly had an impact on the decision. The best known study is probably the work by William Bowen and Derek Bok entitled, "The Shape of the River.,,66 Bowen and Bok utilized a database containing information on over 80,000 undergraduates who attended twenty-eight academically selective colleges and universities in 1951, 1976, and 1989.67 Their work focused on the long-term achievements of the graduates surveyed, such as advanced degree attainment, employment, earnings, job 59. Social science can be defined in many ways. I define social science to mean those empirical studies that generally establish correlation or causation. With regards to affirmative action, social science includes those studies that show the benefits of diversity in schools and cultural bias in standardized exams. 60. See, e.g., Deborah Jones Merritt, AFTERWARD: The Future of Bakke, 59 OHIO ST. L.J. 1055 (1998); Samuel R. Sommers & Phoebe C. Ellsworth, How Much do we Really know About Race and Juries? A Review ofSocial Science Theory and Research, 78 CHI.-KENT. L. REV. 997 (2003); Sharon G. Portwood et aI., Social Science Contributions to the Study of Dqmestic Violence within the Law School Curriculum, 47 Loy. L. REV. 137 (2001). 61. Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908); See also Merritt, supra note 60, at 1055. 62. Id. at 1055-56 (citing Ronald K. L. Collins & Jennifer Friesen, Looking Back on Muller v. Oregon, 69 A.B.A. J. 294,295 (1983)). 63. Brown, 347 U.S. 483. 64. Merrit, supra note 60, at 1057. 65. See, e.g., Sommers & Ellsworth, supra note 60. 66. BOWEN & BOK, supra note 10. 67. Id. at xxvii-xxviii. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 57 2004 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLICY 58 [Vol. 10:39 satisfaction, civic participation, and thoughts on race relations. Bowen and Bok found that African-Americans enjoyed success at rates similar to those of white graduates. For example, in the 1976 entering class, 40% of blacks and 37% of whites went on to obtain doctorates or professional degrees in law, business, and medicine. 68 The study also found that in the 1989 group, over 76% of African-Americans and 55% of white graduates believed that the "ability to 'work effectively' and 'get along? well with people from different races and cultures" was "very important.,,69 A follow up study was conducted by Richard Lempert, David Chambers, and Terry Adams. 70 The Lempert study focused on graduates from the University of Michigan School of Law. Their study showed that despite lower LSAT scores and undergraduate GPAs, blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans fared as well in the legal profession when compared to their white counterparts in the areas of income and career satisfaction. 71 The Lempert study and the BowenIBok study also found that minority graduates tend to have higher levels of civic and community service. 72 With regards to diversity in education, studies have shown that a diverse student body enhances the education of all students. 73 A student body consisting of all white students will not produce the best education for all participants. 74 The same can be said for an all-black or all-Latino student body.75 Without diversity, students are not challenged with new perspectives and novel ideas. Professor Patricia Gurin conducted a study that showed racial and ethnic diversity in the classroom had a positive effect on the learning process, including "engagement in active thinking processes, growth in intellectual engagement and motivation, and growth in intellection and academic skills. ,,76 In the Grutter case, several experts presented testimony regarding the benefits of diversity in education. 77 A number of other studies, including the Harvard Civil Rights Project's Diversity Challenged and the work of Maureen Hallinan, contain research on the educational benefits of affirmative action. 78 For more information on the value of diversity in education, one need only turn to 68. 69. Id. at 98 fig. 4.2. Id. at 220, 222. David L. Chambers et aI., Michigan's Minority Graduates in Practice: The River Runs Through Law School, 25 70. LAW & SOc. INQUIRY 395 (2000). 71. Id. at 442-47. 72. Id. at 500; See also BOWEN & BOK, supra note 10, at 156-174; Merritt, supra note 60, at 1063. Patricia Gurin, Reports Submitted on Behalf of the University of Michigan: The Compelling Need For Diversity 73. in Higher Education, 5 MICH. J. RACE & L. 363 (1999); See also Merritt, supra note 60, at 1062-1063; Maureen T. Hallinan, Diversity Effects on Student Outcomes: Social Science Evidence, 59 OHIO ST. L.J. 733 (1998). Hallinan, supra note 73, at 742. 74. 75. Id. Gurin, supra note 73, at 365. 77. See generally Gurin, supra note 73. 78. DIVERSITY CHALLENGED: EVIDENCE OF THE IMPACT OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION (Gary Orfield &Michal Kurlaender eds., 2001); See Hallinan, supra note 73, at 742. 76. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 58 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE &LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 59 the numerous amicus briefs supporting affirmative action in the Grutter case. 79 Another area that has received much attention in the affirmative action debate is admissions criteria and standardized exams. There is rio question tliat admissions criteria and standardized exams playa significant role in determining the demographics of a student body. When all indications of an applicant's race and ethnicity are removed from an application,SO the admissions committee is stripped of the power to develop a diverse student body. Moreover, if standardized exams are culturally biased, the demographics of a school are again altered by an over-emphasis on an entrance exam score that favors one race over the other. For example, the LSAT, which is the standardized entrance exam used in law schools, has been criticized for having a racial/cultural bias. Even the Law School Admissions Council ("LSAC," the organization that administers the LSAT) states that law schools are misusing the LSAT to the detriment of minority applicants.81 Law schools are over-emphasizing the LSAT when admitting applicants to law school. According to the Law School Admissions Council, the LSAT is a statistical "predictor" that indicates how well a student will do his/her first year in law school. 82 However, the LSAT does not predict whether a student will do well in law school, pass the bar exam, or even make a good lawyer. To use standardized exams as the dominant factor in admissions results in the exclusion of qualified applicants. Bias in standardized exams can be viewed in a variety of ways.83 One study, for example, shows how applicants with similar credentials, such as choice of undergraduate university and GPA, still exhibited a disparity on the LSAT. The LSAC's data illustrates this tremendous disparity between races with regards to the LSAT. 84 According to the LSAC, in the Fall 2002 entering class, there were 4,461 applicants with an undergraduate GPA of 3.5 or better and an LSAT score of 165 or above. Of the 4,461 individuals, there were only 29 African-Americans and 114 Hispanics. 85 If schools over-emphasize the LSAT, as they currently do, the impact on diversity is tremendous. Law schools will 79. Amicus Briefs- United States Supreme Court Summary of Arguments Grutter v. Bollinger, et al. at http://www.umich.edu/-urel/admissionsllegaUgru_amicus-ussc/summary.html (last visited Feb. 20, 2004) [hereinafter Amicus]. In Texas, for example, the Hopwood decision banned the use of race/ethnicity in the application process. 80. Hopwood, 78 F.3d 932. Thus, applications for admission and the LSDAS reports did not include the applicant's race or ethnicity. Admissions Committees were forbidden from taking race into consideration. See Brief of the Law School Admission Council as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, Grutter v. 81. Bollinger, 123 S. Ct. 2325 (2003) (No. 02-241). [hereinafter LSAC Amicus]. 82. Id. 83. See generally Jeffrey S. Kinsler, The LSAT Myth, 20 ST. LOUIS U. PUB. L. REV. 393 (2001); William C. Kidder, Does the LSAT Mirror or Magnify Racial and Ethnic Differences in Educational Attainment?: A Study of Equally Achieving "Elite" College Students, 89 CALIF. L. REV. 1055 (2001). 84. See LSAC Amicus, supra note 81, at 8. 85. Id. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 59 2004 60 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 overwhelmingly admit white applicants over qualified applicants of color. Moreover, the Texas Ten Percent Plan, which admits the top 10% of the graduating class from every high school into public schools of higher education, also reveals the negative consequences of over-reliance on standardized exams. In the Ten Percent Plan, students are admitted based on their grades, not standardized exam scores. On its face, one might argue that unqualified people are being admitted into college. Yet, the opposite is true. Students admitted under the Ten Percent Plan (based on grades alone) have outperformed their peers who were admitted based on traditional SAT standard admissions. 86 While it is clear that there is no correlation between a person's standardized exam score and the likelihood of success in school, there is a correlation between a standardized exam score and the income level of the students' parents. 87 There is a direct relationship between parental income and a student's SAT score.88 Standardized exams reveal more "about past opportunity than about future accomplishments on the job or in the classroom.,,89 It appears standardized exams serve to screen out students of color. Social science research is also informative when studying the disparities in wealth accumulation between the races. Income and wealth are often left out of the affirmative action debate. Yet, income and wealth-accumulation opportunities for people of color have been directly affected by political, legal, and commercial practices and policies. Again, social science presents another dimension to the debate. For years, people of color have been legally deprived of an education and wealth-producing opportunities. 90 Racism embedded in our laws and political systems has had a tremendous effect on the educational and economic opportunities of people of color. When one considers the opportunities lost and the time/value of money, the financial disparities are staggering. For centuries, slaves and African-Americans neither had the right to own property nor the opportunity to accumulate wealth. The impact on today's African-American is significant. One must consider social science and the time/value of money to engage in a real discussion of the topic. To illustrate the value of money over time, imagine two family trees: the family tree of Mr. Smith, a white man, and the family tree of Mr. X, a slave. From 1700 to the present - i.e., five generations - the descendants of Mr. Smith could become 86. See LAN! GUINIER & SUSAN STURM, WHO'S QUALIFIED? 99 (2001) (Students admitted under the Ten Percent Plan have a higher freshman GPA than those admitted using conventional criteria). BELL, supra note 7, at 265-266 (referring to a study by Professors Susan Sturm and Lani Guinier on the 87. Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT), the Law School Admissions Test (LSAT) and the civil service tests. 88. Id. at 266-267. 89. Susan Strurm & Lanie Guinier, The Future of Affirmative Action: Reclaiming the Innovative Ideal, 84 CAL. L. REV. 953, 957 (1996). 90. MICHAEL OMI & HOWARD WINANT, RACIAL FORMATION IN THE UNITED STATES: FROM THE 1960s TO THE 1990s 65-67 (2nd ed. 1994). HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 60 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LA W: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 61 lawyers and doctors as well as own property and save money. They could also pass wealth from one generation to another. On the other hand, the descendants of Mr. X, the slave, would neither have had the opportunity of obtai!ling an education nor could they own property or enjoy any inheritance.. If Mr. Smith had saved $100 in the year 1700 and passed it down from generation to generation (earning 3% annual interest), that same $100 would 91 be worth almost $800,000 in the year 2003. This amount does not take into account the likelihood that the family could have purchased property and passed it down from generation to generation. Not until the 1960s would descendants of Mr. X have had an equal chance to attend college and save money.92 So if descendants of Mr. X had attended college and had saved $100 in 1965,93 the $100 would be worth $316.70 today. When one combines the time/value of money with lost (or usurped) economic opportunities, the tremendous financial disparity between the races is substantial. In Black WealthlWhite Wealth, Melvin Oliver and Thomas Shapiro argue that in order to understand contemporary racial inequality, it is imperative to consider the connection between race and wealth. 94 They introduce the concept of "racialization of state policy" which refers to how governmental policies have impaired the ability of people of color to accumulate wealth.95 They cite several examples, such as red-lining mortgage lending practices (affecting home ownership),96 poor education and other forms of asset accumulation where the laws and the government favored white America to the exclusion of people of color, especially African-Americans.97 They show how the cumulative effects of past historical policies and practices have cemented African-Americans to the bottom of society's economic hierarchy. Oliver and Shapiro argue that segregation, poor education, and low wages affected many generations of blacks and caused "sedimentation of racial inequality.,,98 They also show how white America benefited during the time that AfricanAmericans were economically disadvantaged. 99 In other words, when blacks suffered a "cumulative disadvantage," whites experienced a positive "cumulative advantage."lOo It was not until the late 1960s, with the introduction of affirmative action, that people of color were 91. One hundred dollars with an annual interest rate of 3% compounded annually would yield $798,943.95 in 2003. 92. The 1960s brought the civil rights movement and affirmative action programs. 93. After it was made possible by the implementation of affirmative action programs. 94. OLIVER & SHAPIRO, supra note 24, at 35; See also CHRISTOPHER EDLEY, JR., NOT ALL BLACK AND WHITE: AFFIRMATIVE ACTION AND AMERICAN VALUES 42-52 (1996). 95. OLIVER & SHAPIRO, supra note 24, at 50. 96. Id. at 20 (citing Federal Reserve study indicating discrimination in lending patterns even to wealthy black households). 97. Id. at 11-32. 98. Id. at 50-52. 99. Id. 100. OLIVER & SHAPIRO, supra note 24, at 51. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 61 2004 62 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LA W & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 finally allowed to compete on the same level as the rest of the population. WI Social science materials add a necessary dimension to the affirmative action debate and to any discussion on race and law. v. CRITICAL LEGAL ANALYSIS AND RACE THEORY Within the first few days of law school, students begin to "think" like lawyers; the transformation from an "open-minded, justice oriented, naive student" to "lawyer" begins within the first few days of class. Maybe it is the all-consuming painful law school experience or the overwhelming number of assigned cases to read that drives a student to the point of brushing notions of justice aside. The goal, after all, is to "think" like a lawyer. This means the ability to apply law to various fact patterns with no real consideration of whether the law and/or the outcome is just or fair. Critical legal analysis, on the other hand, requires that one consider the impact of a particular law on society, its evolution, and whether it is fair to all the parties affected. In the study of race and law, one should also engage in critical race theory. While there are many facets to critical race theory, I will only mention a few here. For example, critical race theory considers how the law is shaped. When affirmative action is studied in law school, the discussion often begins with Bakke-the landmark case. 102 After reading so many cases in law school, students often read court opinions in the belief that the holding is all that matters. Colleges and universities have since embraced the principles and standards set forth in Bakke. When reading Bakke, people rarely challenge the absence of other facts and/or the Supreme Court's wisdom in determining the standard to follow in affirmative action cases. Not enough attention is given to the fact that the Equal Protection Clause was enacted to protect former slaves and that the Supreme Court turned the Equal Protection Clause on its head when it used the 14th Amendment to protect a white plaintiff against discrimination. How did that happen? Derrick Bell provides fascinating commentary on the Bakke case. Although the Bakke case would have a significant impact on minorities throughout the 101. Some students have argued that affirmative action is not fair because it discriminates against white students whose ancestors were not slave owners. In 2000, a student in Race & Racism argued that her "ancestors never owned slaves" so why should she pay the price for other peoples' crimes? 102. In 1978, affirmative action was attacked in the Supreme Court case of Bakke v. Regents of University of California. Bakke, a white plaintiff, argued reverse discrimination and that his constitutional rights had been violated. Bakke v. Regents of Univ. of Cal., 438 U.S. 265 (1978). The Supreme Court turned the 141h Amendment on its head and ruled in Bakke's favor. The Bakke court, however, also held that "race" could be used as a factor in admissions and that "targets" such as those used in Harvard were permissible. With that standard, colleges and universities all over the country patterned their admissions programs after the Bakke criteria and followed a model similar to Harvard's. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 62 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LAW: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 63 country, "[m]inority interests were not represented on either side of the counsel table as the Bakke case wound its way through the courtS.,,103 Bakke's counsel opposed minority interests and the University of California took the case to the Supreme Court despite the protests of numerous minority groups throughout the country.104 Prior to the Supreme Court's decision, minority representatives requested a new trial and asked the California Supreme Court to remand the case so that minority interests would be addressed, and to present evidence of these interests. lOs If minority interests had been represented in Bakke, evidence would have been offered on matters such as "past and present discrimination in the California public school system, past discrimination by the UC Davis Medical School itself, and the invalidity of the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) as an indicator of minority performance in medical school. ,,106 The case law developed in Bakke was essentially created and determined by non-minorities. In critical legal analysis one must not only consider how the law is shaped, one should also consider who shapes the law? Professor Bell states that the "star players" in the Bakke case were excluded from the debate. 107 The key people most affected by the decision were excluded from the whole process. Although students of color tried to intervene, the courts closed the door to their participation. The people involved in creating law - judges, lawyers, clerks, legislators, and other elected officials - are important players in shaping law. From the lowest-level law clerk to the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, these players take a role in shaping the law. People are influenced by their personal experiences and biases. In critically analyzing this process, one must not only evaluate the application of the law, but must also remember that it is equally important to consider who shapes the law. For example, in the Dred Scott case, more than half of the Supreme Court Justices - including Chief Justice Taney - were slave owners. Their personal biases certainly influenced the outcome of the case, and this happens too often. Another important aspect concerning how the law is shaped involves "framing the issue." An outcome can often depend on how the issue is framed. For example, in Dred, Scott, Chief Justice Taney affected the outcome by changing the focus of the issue. The Dred Scott question centered on freedom and the circumstances under which a slave becomes free. Chief Justice Taney framed the issue such that the central question was one of citizenship instead of freedom. lOS The outcome of the case was decided the moment the 103. 104. 105. 106. 107. 108. BELL, supra note 7, at 252-53. Id. at 253. Id. Id. at 254. /d. at 253. Scott, 60 U.S. 393. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 63 2004 64 TEXAS HISPANIC JOURNAL OF LA W & POLICY [Vol. 10:39 issue was framed in this manner. The same can be said about Plessy v. Ferguson,109 Bakke, Hopwood, and many other cases involving race. Our legal system is based on the principle of stare decisis which is Latin for "to stand by a decision." In other words, courts rely on previous judicial decisions, unless they contradict contemporary notions of justice. The theory behind stare decisis is that the legal system will produce fair and just laws because they have been tested over time. In many respects, this makes sense. Yet, stare decisis, and its reliance on precedent, ensured centuries of bad laws with regard to race in American society. How valid is precedent in cases involving race? We now know that Dred Scott was wrongly decided. We also know now that Plessy v. Ferguson was wrongly decided, as was Hopwood. Furthermore, all the cases that relied on Plessy v. Ferguson for precedent were wrongly decided as well. We must acknowledge that despite the greatness of our system, its· imperfections have generated a tremendous cost. In matters of race, we can go back in time and find hundreds of cases that were obviously wrongly decided. In an age of colorblind arguments, it is worth noting that race-neutral laws do not mean they are free of racism and discrimination. America's Word Smiths are very good at writing laws that appear to be race neutral, but are in fact discriminatory in application. For example, consider the following apparently race-neutral laws: poll tax ordinances; voting literacy requirements; California's Propositions 54, 187, and 209; federal inheritance tax breaks; mortgage loan deductions; capital gains tax breaks; English-only laws; school vouchers; and, of course, the United States Constitution as it was written in 1778. We still have a way to go. Critical race theory requires that students engage in analysis that goes far beyond a typical "legal analysis." VI. CONCLUSION On June 23, 2003, the Supreme Court of the United States issued its opinion on the University of Michigan School of Law's affirmative action case-Grutter v. Bollinger. no Historically no other Supreme Court case has received as much attention as Grutter v. Bollinger. Over eighty-five amicus briefs were filed l11 and every major magazine and newspaper in the country published commentary or analyses on affirmative action. For more than one year, the University of Michigan Law School's affirmative action case caught the country's attention. 109. Plessy, 163 U.S. 537. 110. Grutter v. Bollinger, 123 S. Ct. 2325 (2003). 111. Sixty-nine amicus briefs were written in support of the University of Michigan's affirmative action program. See Amicus, supra note 79. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 64 2004 2004] PEDAGOGY ON TEACHING RACE & LA W: BEYOND "TALK SHOW" DISCUSSIONS 65 Many scholars argue that the country has not confronted racism head on and, as a consequence, racism remains a fundamental impediment to a just and equal society.ll2 If we are ever to get beyond racism and create the kind of world where people respect each other in every way, we must first see-k to understand racism in order to develop a fair multiracial/cultural society. As evidenced by the political buildup to the Grutter decision, racial tensions in America are real. In order to move beyond racism and achieve racial healing, we must take race into account. This is not an easy task. To create a future that is profoundly better than the past, it is imperative that we study the roots of racism and its historical context so that we may realize how we have arrived at where we are today. We cannot pretend to live in a color-blind society if discrimination remains a reality. As has been said many times, "[t]o oppose racism one must notice race." By recognizing racism, its roots, and its manifestations, we can challenge it and its "reduction of the human experience."113 Because race and racism are tightly interwoven into our political and legal systems, it is essential that teachers at all levels-especially law professors-make a conscious effort to include racial issues in education. In this respect it is important to go beyond "talk show" discussions when teaching and studying race-based subjects. This requires a more comprehensive study of the connection between race and law. By including history, statistics, and social science, the instructor allows the student to make balanced assessments of all the aspects of this issue. To rely solely on a few cases or statutes provides an incomplete picture of reality. To ensure our nation evolves and reaches its greatest potential, we must ensure respect and equality among all ethnic, racial, and multi-cultural groups. Every year the United States becomes more diverse in culture, race, and ethnicity. This trend will not stop anytime soon. The ideas set forth in this writing barely touch the tip of the iceberg. We must be ambitious in our goal of improving the relationships within our multi-cultural and multi-racial society. This is the ultimate goal: to lay the foundation for a better world. 112. W. E. B. Du Bois predicted that the "color-line" would be the major issue of the 20'h Century. BELL, supra note 7, at xii. 113. Omi & Winant, supra note 90, at 158-159. HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 65 2004 HeinOnline -- 10 Tex. Hisp. J.L. & Pol’y 66 2004