Do we really want a tax system James R. Hines Jr.

advertisement

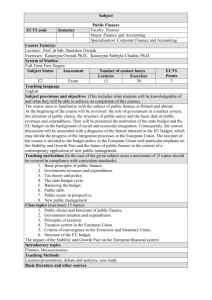

Do we really want a tax system with a broad base and low rates? James R. Hines Jr. University of Michigan and NBER London December 9, 2014 The answer, it seems, is obvious. • Many people think they want a tax system with a broad base and low rates. • Why? Low tax rates are attractive. Everybody likes low tax rates. Low rates mean low burdens. • Furthermore, is it not the case that an efficient tax system has low tax rates? Well, no. • It is certainly inefficient to have an arbitrarily differentiated tax base with random tax rates. • But an efficient – and equitable – tax system has a rather narrow base and rather high rates. Therein lies the rub. Haven’t we been told that a broad tax base is better? • Yes, we certainly have. • Robert Murray Haig (1921) and Henry Calvert Simons (1938) sketched what is now known as Haig-Simons taxation. • Haig-Simons taxation is very inclusive taxation: its taxable income is the sum of consumption expenditure plus the change in an individual’s net worth. • Haig-Simons taxation taxes every source of income, including unrealized capital gains (on your home, for example) and gift receipts. • No deductions, credits, or exemptions. • Simons defended it on the basis of its “aesthetics.” What have we been told recently? • Much of the political discourse suggests that we can solve our fiscal problems by broadening the tax base. • The common narrative is the following: ▫ There is base erosion attributable to unwarranted tax breaks for special interests. ▫ Eliminate these tax breaks, and there will be tax revenue to fund government programs and/or reduce tax rates. ▫ Furthermore, eliminating these tax breaks makes the economy more efficient by reducing tax-motivated activities. • How many unwarranted tax breaks are there in the United States and the United Kingdom? It is hard to say. Tax expenditures • There is something called the “tax expenditure budget.” • The concept – which dates back to Stanley Surrey 40 years ago – is to measure the extent of special tax preferences, and treat them as though they were government spending programs. • Consider the case of charitable deductions: ▫ If taxpayers are permitted to deduct charitable contributions from their taxable incomes, the government implicitly subsidizes charities. ▫ Surrey would treat this as though the government collected tax without permitting the deduction, then took the money and spent it directly on charity. Charitable contributions • Consider a taxpayer with income of $100,000, who faces a 40 percent tax rate. • If the taxpayer does not contribute to charity, he pays tax of $40,000 (40 percent of $100,000), and has after-tax income of $60,000. • If the taxpayer gives $10,000 to charity, and is permitted to deduct the contribution from taxable income, then he has taxable income of $90,000, and pays tax of $36,000 (40 percent of $90,000). • The taxpayer then has after-contribution disposable income of $54,000: $100,000 pretax income minus $36,000 tax minus $10,000 charitable contribution. • Contributing $10,000 to charity costs only $6,000 if contributions are deductible at a 40 percent tax rate. • The result: the tax system encourages charitable contributions. • And the tax expenditure budget treats the $4,000 of foregone tax revenue as a “tax expenditure” by the government. Other tax expenditures • There are many other tax expenditures, including… ▫ Child tax credits. ▫ Earned income credits for low-income workers. ▫ Non-taxation of the imputed rental income on owneroccupied housing. ▫ Deferred taxation of value accumulation in employerprovided pension plans. • • • • What counts as a “tax expenditure”? Anything that is a deviation from “normal taxation.” What is that? It is rather in the eye of the beholder. The notion is that Haig-Simons taxation is a normal tax system, and any deviation is an expenditure. Are there many tax expenditures? • Yes. • The United States was the first country to produce a tax expenditure budget, but now many countries do so. • Since tax expenditures are rather subjective, different countries define them differently, so the tax expenditure budgets are not quite comparable. • It is nonetheless interesting to see how very large these tax expenditure budgets are. • And the answer is: large. In the case of the United States, annual income tax expenditures are about $1.4 trillion, or roughly equal to the size of total income tax collections. • It is not quite correct to say that if we eliminated all the tax expenditures we could cut all tax rates in half, but something close to that is correct. Composition of U.S. tax expenditures • Most U.S. tax expenditures are tax breaks for individuals, not corporations. • The biggest U.S. tax expenditure is the non-taxation of employer provided health benefits. • Many of the other large U.S. tax expenditures concern the taxation of capital income: ▫ Favorable taxation of capital gains. ▫ Favorable treatment of retirement plans. ▫ Favorable treatment of owner-occupied housing. • The recent growth of tax expenditures is largely attributable to expanded social programs, such as the child credit and the Earned Income Tax Credit. U.S. Income Tax Expenditures Top 15 US Tax Expenditures, 2015. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Exclusion of employer provided health care Capital gains (including owner-occupied homes) Employer retirement plans Deductibility of state/local taxes Exclusion of imputed rental income on homes Deferral of foreign income Deductibility of home mortgage interest Charitable contributions Exclusion of interest on state/local bonds Social security for retired workers Treatment of qualified dividends Child credit Exclusion of interest on life insurance saving Individual retirement accounts Lifetime learning tax credit $ 207 billion $ 158 $ 129 $ 83 $ 80 $ 76 $ 74 $ 57 $ 35 $ 30 $ 27 $ 24 $ 23 $ 17 $ 15 U.S. Tax Expenditure Growth International comparisons • As mentioned, it is not really right to compare tax expenditures across countries, since each defines the concept differently. • In addition, it is not right to add the tax expenditures together, because they interact with each other. ▫ U.S. example: $80 billion for excluded imputed rental on homes, plus $74 billion for deduction of mortgage interest. ▫ But if we actually taxed the imputed rental income on homes, we would give a deduction for mortgage interest. • That said, it is of course interesting to do some international comparisons. • Countries seem to differ, with the U.K. possibly a world leader in tax expenditures. • Note: relatively little goes to specific industries. Numbers of Tax Expenditures Income Tax Expenditures All Tax Expenditures Income Tax Expenditures Advantages of reducing or eliminating tax expenditures. • Generates revenue that can be used to reduce tax rates. • Reduces economic distortions attributable to some activities receiving favorable tax treatment. • Produces a more equitable distribution of tax burdens. • Prevents governments from excessive meddling in the private affairs of its citizens. • It would indeed be remarkable for a single set of potential tax reforms to produce so many advantages. Costs of reducing or eliminating tax expenditures. • Produces a less equitable distribution of tax burdens. • Makes the economy less efficient. • Therefore makes it harder to raise revenue. It is very difficult for governments to impose taxes that are inefficient and widely viewed as inequitable. • If the United States were to adopt a Haig-Simons income tax, the only tax policy role of Congress would be to choose tax rates. • Should we worry about what Congress might do with all the extra time? Equity and U.S. tax expenditures. • The United States offers a child tax credit, which reduces the tax burdens of families with children compared to otherwise-similar families without children. • Is that a good thing to do? The political system has decided that it is. • And it is certainly true that a family with two children and an income of $50,000 is less well-off than a family without children and an income of $50,000. • People choose to have children, so should we permit them to have a tax reduction on this basis? • Reasonable minds might differ on this question, but the majority feels that the answer is yes. More tax expenditure equity. • The United States offers a casualty loss deduction. • Taxpayers can deduct losses (above a minimum amount) from fire, theft, storms, shipwreck, etc. from their taxable incomes. • Example: your employer pays you $500 (gross) at the end of the week. • You take the check to the bank, ask for cash, and on the way out of the bank are robbed at gunpoint (this happens all the time in America; have you seen the movies?) • You are permitted to deduct the theft loss from taxable income, so need not pay taxes on the wages. • But this deduction is considered a “tax expenditure.” Are all tax expenditures of this ilk? • There is enormous variation. • Many tax expenditures have the effect of reducing the taxation of capital income. • If I loan you $100 for a year, and you pay me $5 interest, I get to spend $105 next year in return for waiting. • Is it equitable to tax me on the $5? • All that has happened is that you consumed the $100 this year instead of me, and the $5 is the amount you are willing to pay (and I am willing to accept) for the deal. • Many argue that it is equitable not to tax the payment for waiting to consume. There is extensive debate over this question. • The issue of whether or not to tax capital income is entirely separate from the issue of how progressive to make a tax system; a tax system that does not tax capital income can be made very progressive, indeed possibly more progressive, than a tax system that does. Tax expenditures and efficiency. • Would eliminating all tax expenditures make the economy more efficient? • Surely not. • The most inefficient taxes are thought to be those on capital income, because such taxes compound over time and across income sources. • At an interest rate of 5%, a 40% tax rate reduces the after-tax rate of return to 3%. • This reduces the total return on a 25-year investment from 239% (pretax, at 5%) to 109% (after tax, at 3%), which is a wedge of 54 percent. • In addition to discouraging saving and investing, capital income taxes discourage labor supply directed at earning income to be saved for later consumption. More efficiency. • But would it make the tax system more efficient to eliminate, say, the charitable deduction and use the additional tax revenue to lower statutory tax rates? • No; not if the charitable deduction is there for a (good) reason. • Consider the taxpayer in a 40 percent tax bracket who gives 10 percent of his income to charity. • He is now effectively taxed at 36 percent on his labor income, bearing in mind that he will devote some of it to charity. • If the government were to eliminate the charitable deduction and reduce the top tax rate to (say) 38 percent, then the tax rate on this taxpayer’s marginal labor income would actually go up. • The actual effects will vary across taxpayers, but the general point is that incentives to earn income depend not only on the statutory tax rate, but also on deductions, credits, and other tax benefits associated with what one plans to do with additional income. Marginal tax rates. • There is a much broader point: that a revenue-neutral tax reform MUST increase some marginal tax rates. • It is tempting to think that a revenue-neutral tax reform that eliminates some tax deductions or credits, using the additional revenue to reduce statutory tax rates, creates greater incentives to earn income. • But this is wrong. Why? • Because it is IMPOSSIBLE to reduce some marginal tax rates, leave others unchanged, and still have a revenueneutral tax reform. Reducing marginal rates means that you get less tax revenue (except in the very unusual case that tax rates are above the peak of the Laffer curve). Other efficiency considerations • Activities that create significant benefits for others, and are therefore otherwise undersupplied, are good candidates for favorable tax treatment. • These are “Pigouvian subsidies.” Examples: ▫ Tax deduction for charitable contributions. ▫ Research tax credits. • The flip side is that activities that create significant harms to others, and are therefore otherwise oversupplied, are good candidates for additional taxation. These are “Pigouvian taxes.” Examples: ▫ Taxes on environmental pollutants. ▫ The London congestion charge. • This leads to a highly differentiated tax system, a stark departure from Haig-Simons taxation. Efficient and inefficient taxation • All taxation is inefficient: ▫ Income taxation discourages income production. ▫ Corporate income taxation discourages investment. ▫ Value added taxation discourages production of value added. • The challenge is to find the most efficient way of raising revenue with a fair distribution of burdens. • It is particularly inefficient to offer arbitrary tax benefits to selected individuals, industries, and activities, if that is what tax expenditures do. (Is that what they do?) • But there is no presumption that all income should be taxed at the same rates. The inevitable distortions are minimized by taxing some activities, and some individuals, at lower rates than others. What else? • Highly elastic economic activities – those that respond most sharply to taxation – should be taxed at lower rates than less elastic activities. • For example, tax rates on international commerce are optimally lower than tax rates on less-elastic domestic activities. ▫ Put a heavy tax on international shipping and it just sails away. • Similarly, different individuals should be taxed to differing degrees. Efficient income taxation. • Efficient taxation entails “tagging”: adjusting tax burdens, and tax rates, to individual situations, rather than applying the same system to everyone. • For example, a 30-year-old usually has greater earning potential than a 70-year-old, so the tax system might offer extra breaks to 70-year-olds. • We do this for two reasons: ▫ The 70-year-olds are poorer. ▫ Income production by 70-year-olds may be more responsive to taxation: they can retire and spend down their savings. • As a general matter, adjusting tax burdens by age makes the system better tailored. • But age-specific tax breaks can be described, and are usually crafted to look like, narrowing the tax base. Efficient taxation (2). • Age is just one example. • Efficient taxation uses information beyond reported income to adjust tax burdens. • Taller people earn more than shorter people; men earn more than women; college graduates earn more than others. ▫ These are no more than average tendencies. ▫ Is it right to adjust tax burdens on the basis of criteria such as these? ▫ It has been shown that efficiency improves if the system (properly) treats taxpayers differently. Another example: business meals • Should the costs of business meals be deductible? • Yes, if they are really business expenses; no, if they are personal expenses. • Taxpayers differ in the extent to which these meals are work v. pleasure. • The tax system applies a single rule (US: 50 percent deductible), which is usually wrong (in both directions). • How should the rule be chosen? It should be sensitive to the extent to which it creates incentives for too many, or too few, business meals. This is a function of whether those who like, or hate, business meals are more apt to vary their behavior in response to tax incentives. • Note: there is no presumption that reducing or eliminating the business meal deduction enhances efficiency. Efficiency requires balancing the costs of too many and too few tax deductions for business meals. Four reasons to deviate from comprehensive income taxation. • Tailoring taxes to individual situations (e.g., child tax credit or age-based taxes). • Imposing taxes on less-elastic activities and not on highly elastic activities (e.g., exemption of foreign income of multinational firms). • Avoiding tax compounding (e.g., favorable tax treatment of pensions and other saving for retirement). • Pigouvian subsidies for efficiency-enhancing activities (e.g., research tax credits). Can politicians handle tax complexity? • Some feel that it is better to stick with the story line that a broadbased, low-rate tax system is better than the alternatives. • The concern is that once we acknowledge the truth that efficient taxation is highly differentiated, it will be open season for special interests to claim that they are (all) worthy of favorable tax treatment. • If the political process delivers tax breaks to special interests that lobby effectively, the product can be a very inefficient tax system. • There is another possibility: that the political system works reasonably well, and that major tax reforms that lower rates and broaden tax bases are customarily followed by higher tax rates and more narrow bases because the tax system is actually better that way. • Do it really improve policy to push a line that is inconsistent with the theory of taxation as we understand it? U.S. Income Tax Expenditures How taxpayers feel • Voters say they want: ▫ Tax simplicity. Makes the system easier to understand, and prevents others from getting unwarranted tax breaks. ▫ Lower tax rates. • But that said, many specific tax breaks (in the US, owner-occupied housing; charitable contributions; employer provided health care and pensions; state/local taxes;…) have considerable political appeal. • Governments need revenue, and it is never going to be popular to get that revenue through taxation. • But our history suggests that governments are aware of the need for tax policies that are sensitive to individual situations and economic conditions. Where does this leave us? • There is no principle of efficiency or (non-tautological) equity that implies that the best tax system taxes a very broad definition of income at relatively low rates. • Far from it: the prevailing theory is that taxation should be highly differentiated and individualized. The most efficient and equitable system has a relatively narrow tax base with relatively high tax rates. • Proposals (and there are some) to cap all tax deductions, or reduce all tax deductions by a fixed fraction (say, by letting people claim only 80 percent) look odd through this lens. • The truth is messy, good policy is messy, and we have no choice but to rely on governments to make it for us. • That they have done so with many tax credits, deductions, and exemptions is not necessarily a bad thing. These governments may have much clearer appreciation of the nature of the tax problem than that with which we often credit them.