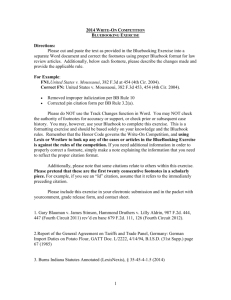

AN UN-UNIFORM SYSTEM OF CITATION: BLUEBOOK Rules Concerning Citation Form)

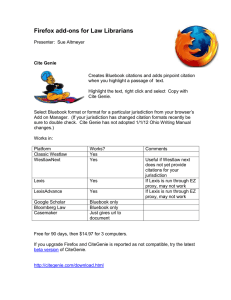

advertisement