PASSAGE OF A MINIMUM COMPETENCY TEST AS

advertisement

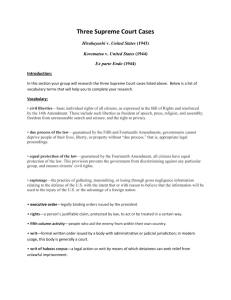

PASSAGE OF A MINIMUM COMPETENCY TEST AS A REQUISITE FOR RECEIVING A HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA: THE FIFTH CIRCUIT STANDARD FOR LEGALITY Frank April Texas For: Prof. 00522- R. Waite 15, 1983 Tech School of Law Independent Research 721 Thomas E. Baker PASSAGE OF A MINIMUM COMPETENCY TEST AS A REQUISITE FOR RECEIVING A HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA: THE FIFTH CIRCUIT STANDARD FOR LEGALITY Introduction In response to public concern that many high school graduates cannot read, write, or compute at minimum levels of adult proficiency, more than forty states have adopted some form of standardized testing as an approach to the problem.1 (throughout this paper such tests will be referred to as minimum competency tests, MCTs). Despite apparently overwhelming political support for such testing as an expedient and effective method of improving public education, there has been widespread criticism of the exams from pedagogical and legal perspectives. The criticism are based primarily on the different purposes for which the exams are used. When the MCTs are given to students to monitor the quality of education which the schools provide and for allocating educational resources on that 2 basis, there seems to be very little objection. But, controversy arises when the tests are given to determine whether a high school student has obtained a high enough level of functional literacy (competency) to be granted a diploma. This method of using the MCT shifts the burden of poor schooling onto the students. It Is this diploma sanction that draws the legality of MCT into question. "The legality of a testing program will usually depend more upon the use of the test results than upon the test itself. Using the test results as the primary basis for any decision that will cause serious harm to a student 00523 -1- raises initial legal questions. The trigger for legal analysis 3 is this injury." This paper will explore the legality of the diploma sanction under the United States constitution and federal statutes as it is utilized in the Florida accountability program Lj. which has been interpreted by the Fifth Circuit in 5 Debra P. v. Turlington. In examining the MCT controversy it is necessary to make a distinction between the legal and constitutional attacks on the diploma sanction versus the soundness of the diploma sanction as educational policy. This distinction is critical in understanding that even if the educators reach a consensus that the diploma sanction is unwise education policy, there may be no viable challenge to the legality of the sanction under federal law. The pedagogical criticisms emphasize the adverse effects that allocating educational resources toward minimum g competency rather than overall program breadth and quality. The argument is that education will be geared toward minimum standards at the expense of college prepatory and educationally 7 esoteric programs. Some educators also fear that students may drop out of school rather than risk obtaining a certification as holders of less than a diploma. Although these criticisms may have merit, the policy decisions are within the legitimate authority of state legislatures to make and the courts will not interfere unless the harm to students is a clear afront to constitutional or statutory rights. g This writer knows of only two cases litigating the legality 9 of MCTs with a diploma sanction. Debra P. v. Turlington -2 is the only appellate court decision. The legal claims asserted were violations of students rights under the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment 10 and violations of Federal Statutory Rights Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 11 and the Equal 12 Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA). Before detailing the claims and holdings in Debra P. it will be useful to consider conceptually how a MCT could be attacked under the Fourteenth Amendment. Under the equal protection and the due process clause 13 if no suspect class or fundemental right is involved, the state may utilize any means which is Irrationally related to legitimate purpose. In this situation the legitimate state purpose is to restore confidence in public education and make a high school diploma more meaningful. The potential constitutional violations are in finding the means are irrational or arbitrary. This is where the scientific validity of the exams is called into question. If the exam lacks validity it is not rationally related to a legitimate state purpose and is thus unconstitutional. The allocation of the burden of proof in fourteenth amendment litigation is often critical. In the standard application of the rationality test the plaintiff will have to carry the burden of showing the MCT to be invalid against a presumption of constitutionality. However, in some instances it is possible to shift the burden back onto the state. This is because in a post desegregation setting the state carries the burden of showing the constitutionality of its actions 00525- which have an adverse disproportionate impact on minority students. 15 The discriminatory impact by itself does not 16 shift the burden; but, if the state has a history of de jure segregation, there will be a presumption against the constitutionality of state action taken which results in a racially discriminatory impact. 17 The state carries the burden of justifying their action at a higher level of 18 judicial scrutiny than rationality. The question whether Title VI and the EEOA claims parallel the fourteenth amendment challanges to MCTs has not been specifically delineated in any case law. It is the purpose of this paper to examine this issue in depth. The analytical method used will be to examine the Fifth Circuit court's holding in Debra P. and to project how the case may be decided on remand applying the Circuit's constitutional and statutory standards of reviewing the use of MCTs for granting high school diplomas. The Florida MCT - Debra P. v. Turlington In 19 76, the Florida Legislature enacted a comprehensive piece of legislation known as the "Educational Accountability . . .intent was to provide Act of 19 76."19 The state legislative a system of accountability in order to guarantee that each student be afforded similar opportunities for educational advancement without regard to geographic differences varying local factors, and to provide an information basis on which education decision makers could rely in allocating resources to meet the needs of public education. 00526- The system was also designed to guarantee to each student that instructional programs meet minimum performance standards set by the State Board of Education. Information was to be provided to the public on the performance of the system toward meeting established goals of providing effective, meaningful, and relevant educational experiences designed to give students 20 skills necessary to function and survise in today's society. In 19 78, the Legislature amended the. Act to require students to pass a functional 21 literacy exam in order to receive a high school diploma. The test was entitled the State Student Assessment Test (SSAT II) and was first administered in the fall of 19 77. Substantial numbers of students failed the test, with a higher percentage of black students failing than whites. 22 A class action suit 23 was brought in federal district court challenging the constitutional and statutory validity 2 of the test. The Court held for the plaintiffs finding that (1) in light of past purposeful discrimination immediate use of the test perpetuated the effects of a segregated school system in violation of the equal protection clause, Title VI and the EEOA; (2) the test had adequate content and construct validity and was rationally related to a legitimate state interest; (3) the test was not racially of ethnically biased; (4) the failure to apply the test to private schools was not unconstitutional; (5) the inadequacy of notice provided prior to the use of the diploma sanction was a violation of the due process clause; (6) using the test to classify students for 00527 - 5- remediation was constitutionally permissable, and (7) the state would be enjoined from requiring passage of the test a requirement for graduation for a period of four years, which is twelve years after the abolishment of the states's dual school system. Both parties appealed the district court decision. 2 5 Florida contended that the district court erred in finding that the test violates due process because there was adequate notice and no property right was involved. They also contended that there was no equal protection violation and that Title VI and the EEOA should have been found inapplicable to the case. Appellees on cross-appeal contended that the district court erred in limiting the period of the injunction to four years and in upholding the validity of the exam. The Fifth Circuit held the finding of the trial court that the exam had adequate content validity to be clearly erroneous, on the record presented. The judgment of the lower court was vacated and the case remanded for further findings of fact on the question whether the exam covered only that which was taught in the school system. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the lower court's finding that students had a property interest in a diploma which invokes due process clause protection. While the court affirmed that MCTs with a diploma sanction do not per se fail the rationality test, it also held that if the exam lacked content validity, it would violate the due process and equal protection clauses as well as Title VI and the EEOA. Left open for re-examination on remand was the subject CJ)528 of vestiges of a past dual school system. If the state can demonstrate that the exam is a fair test of that which is taught, they still must meet an affirmative duty to eliminate and not perpetuate the effects of past purposeful discrimination. In other words, even if the exam passes a rationality test it may be constitutionally impermissable if its disparate impact on minority students is the result of vestiges of a dual school system. Additionally, the court held there was no constitutional violation in the exams being required only 26 in public schools. Finally, the circuit court affirmed the trial court holding that MCTs for remediation purposes were constitutionally valid even if the tests had a racially discriminatory impact, If the result was to provide minority 27 students with better educational opportunities. The Fifth Circuit Standard Because of the discriminatory impact the exam had on minority students coupled with Florida's history of past 28 de jure segregation, the Fifth Circuit holding Is based as much on civil rights law as it is on the substantive legality of the MCT diploma sanction. The case illustrates that in a post de jure segregation setting the state will carry a heavy two-pronged burden in establishing the legality of its diploma sanction exam under federal law. First, the state must prove that the exam is a fair test of that which was taught In the public school system. Secondly, the state must prove the racially disproportionate MCT results are not caused by vestiges of the past dual school system or that use of 00929- the exam is necessary to provide minority students better educational opportunties. In analizing Debra P. as it may be decided on remand under this standard, this paper will proceed as if it is possible for the state to meet its burden 29 of exam validation. The analysis here will focus on the question of vestiges of a past dual school systems and remedies mandated by the constitution and statutes. The Debra P. decision seems to indicate that in a state with no history of de jure segregation or only de facto segregation, the MCT with a diploma sanction could be used without violating federal law, if the testing instrument is valid. The MCT would be rationally related to a legitimate state purpose. This would be true even if the MCT had a discriminatory impact on minorities. In such a setting, state actions carry a presumption of constitutionality. 3 0 The plaintiffs would have to prove intent to discriminate to make out an equal protection violation. 31 Despite judicial notice of past de jure segregation and social problems during 32 the transition phase to a unitary school system, the district court in Debra P• placed the burden of showing present discriminatory intent on the plaintiffs. discriminate was found. No present intent to An equal protection and statutory violation was found only insofar as the exam perpetuated the effects of past purposeful discrimination while there were still students in the present system who had been subjected to the old dual school system. After the last students who had attended the dual system had completed their education, 00930- the court recognized no other vestige of the old dual school 33 . . system. The Fifth Circuit decision shows the narrowness of this holding as well as the allocation of the evidentiary burden to be a faulty application of desegregation case law. In light of the trial court's findings of past de jure segregation, the burden of showing the constitutionality of the MCT was on the state, and the plaintiffs are not required to show discriminatory intent in order to establish a constitional or statutory violation. The allocation of evidentiary burden might be criticized on the basis of some recent case law tsrhich indicates that the courts are becoming reluctant to carry the presumption of unconstitutional action indefinitely against formerly de jure segregated systems. The Fifth Circuit upheld a district judge's decision that said the court is without power, in the absence of a showing of present intent to discriminate, to find a constitutional violation after a school district has been in "substantial compliance" with its desegregation plan and 34 has operated a unitary school district. In another post de jure segregation setting, the Fifth Circuit refused to place the burden on the school district to show that they had not intentionally discriminated when there was a finding that school segregation was the 3 5 "natural consequence" of area population -distribution. and inconsistent The theory is that it is unfair with the Supreme Court's holding that intent to discriminate q c is a necessary element to a equal protection violation to continue a presumption against school districts. 37 This theory has been directly refuted, however, in school desegregation cases that followed the Courts decisions requiring the discriminatory intent element. In Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 39 Education v. Brinkman, 38 and Dayton Bd. of the Supreme Court reiterated the continued vitality of the Keyes and Swann presumption. The Court explicitly rejected arguments that direct evidence of discriminatory intent was required to prove an equal protection violation in systems where historic de jure segregation was found. Deb^a- P. it is clear that the Circuit court has not shifted the burden back to the plaintiffs to show intent to discriminate as necessary for an equal protection violation. On remand it will be Florida's burden to demonstrate that the disproportionate impact the MCT diploma sanction has on minority students is not a vestige of the past dual system, or that 4-0 such a test procedure is necessary to remedy such vestiges. Desegregation Under the Equal Protection Clause Following the Supreme 4-1 Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown I), holding that separate educational facilities were inherently unequal and a violation of the equal protection clause, a long line of cases has established the constitutional duty to dismantle dual school systems and eliminate their vestiges. In Brown v. Board of Education 42 (Brown II), the Supreme Court delegated to the federal district courts the responsibility to see that the transition to unitary school systems was carried out "with all deliberate , „ M- 3 speed." 0053? The standard of all deliberate speed was abandoned when it became clear that many school districts "persisted in the 44 use of dilatory tactics to avoid complete desegregation." In Griffin v. Prince Edward County Board of Education, 45 the 46 court stated "the time for mere deliberate speed has run out." The Court began to shape a doctrine that would allow the lower federal courts to do more than review whether or not a school district was segregated. 47 In Green v. County School Board, the court reviewed the nature of the school district's effort to desegregate and held that its "freedom-of-choice" plan could not be accepted as a sufficient step to effectuate the transition to a unitary school system. The burden on a school board today is to come forward with a plan that promises realistically to work, and 48 promises realistically to work now." The Court also stated that school authorities are "clearly charged with the affirmative duty to take whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch." 49 50 In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenbrug Board of Education, the Court began to elaborate on the affirmative duty and how it is discharged. "The objective today remains to eliminate from the public schools all vestiges of state-imposed segre• gation." 51 Broad guidelines were set for the district courts to review the efforts of school authorities. 00533- "If school authorities fail in their affirmative obligations under these holdings, judicial authority may be Invoked. Once a right and violation have been shown, the scope of a district court's equitable powers to remedy past wrongs is broad, for breadth g 2 and flexibility are inherent in equitable remedies." The Supreme Court recognizes that reviewing desegregation efforts is largely a qualitative matter. The court must look at the "root and branch," "vestiges" of a district's segregation in formulating a remedy. (A examination Into the concept of vestiges is made in a later section of this paper.) Limitation of district court's power to remedy discrimination is found in the distinction between de jure and de facto segregation In Keyes v. School District No. 1 53 the Supreme Court made it clear that only de jure segregation, defined as, "a current condition of segregation resulting from intentional state action," 5 M- violates equal protection. This doctrine 55 was again used in Milliken v. Bradley (I), where the Court struck down the district judge's order that area suburban schools be ordered to participate with the Detroit school district in a desegregation plan. The Court held that not- withstanding evidence that Detroit schools were unlawfully segregated, inter-district relief could not be imposed on surrounding school districts. The court stated that the controlling equity principle is that "The scope of the remedy is determined by the nature and extent of the constitutional violation."^ ^ In sum, it is clear that under the fourteenth amendment courts have broad equity powers to remedy discriminatory and segregative actions and omissions by school authorities. 00534- However, this power cannot be invoked unless invidious intent to discriminate is found to presently exist or to have been practiced in the past. The remedy ordered by the court must be limited to the extent of the constitutional violation. The EEOA The Debra P. plaintiffs also challenge the MCT with a diploma sanction under the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974, 57 Section 1703 (b) which states: "No state shall deny equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin, by - . . . (b) the failure of an educational agency which has formerly practiced such deliberate segregation to take affirmitive steps, consistent with subpart 4 of this title to remove the vestiges of a dual school system;" Although no provisions of the Act expressly incorporates the fourteenth amendment, the language of §1703 is obviously very much like that found in the desegregation cases under the fourteenth amendment. But without an express incorporation, legislative intent and court interpretations must be examined to understand meaning of the Act. Two important issues arise. First, is the question whether the duty to "take affirmitive steps to remove vestiges of a dual school system" is substantively the same as the duty required by the fourteenth amendment. Second, is the question whether remedies under the 58 Act are the same as those under the constitution. The relation of the EEOA to the fourteenth amendment is analagous to whether other Civil Rights statutes (Titles VI and VII) are co-extensive with the constitution, so an examination of cases addressing that issue will be explored also. 00535 -13- The declared congressional policy behid the EEOA is that'll) all children enrolled in public school are entitled to equal educational opportunity without regard to race, color, sex, or national origin; and (2) the neighborhood is the appriate basis for determining public school assignments. In order to carry out this policy, it is the purpose of this part to specify appriate remedies for the orderly removal of the vestiges of the dual school system. Because the EEOA was offered as an amendment from the floor to the Education Amendments of 19 74, specific legislative history is strikingly sparse. There are no hearing or committee reports on the Act's provisions. However, it is clear that the Act is essentially the same as the proposed 60 EEOA of 19 72, which passed in the House but not the Senate. There were extensive hearings held on the 19 7 2 Act and some insight into the 1974 Act can be gleened from examination of those House Reports. The legislators seemed primarily concerned with the wisdom and effectiveness of various student transportation remedies that were being imposed by courts in desegregation cases. Congressman Esch's summarized legislative intent of the 19 7 2 Act as, "The purpose clearly, when the act was passed by this House overwhelmingly in August of 19 72, was to suggest that, while we recognize that every child should have an opportunity to be fully educated, the House went on record as emphasizing that the education should be 61 done insofar as possible in a neighborhood school." That the focus of the legislators' attention was primarily on student transportation and not the creation of new substantive rights, is also clear from the face of the congressional findings stated in the 1974 Act: "(a) The Congress finds that(1) the maintenance of dual school systems in which student are assigned to school solely on the basis of race, color, sex, or national origin denies to those students the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the fourteenth amendment; (2) for the purpose of abolishing dual school systems and eliminating the vestiges thereof, many local educational agencies have been required to reorganize their school systems, to reassign students, and to engage in the extensive transportation of students; (3) the implementation of desegregation plans that require extensive student transportation has, In many cases, required local educational agencies to expend large amount of funds, thereby depleting their financial resources available for the maintanance or improvement of the quality of educational facilities and instruction provided; (4) transportation of students which creates serious risks to their health and safety, disrupts the educational process carried out with respect to such students, and impinges significantly on their educational opportunity, is excessive; (5) the risks and harms created by excessive transportation are particularly great for children enrolled in the first six grades; and (6) the guidelines provided by the courts for fashioning remedies to dismantle dual school systems have been, as the Supreme Court of the United States has said, "incomplete and imperfect," and have not established, a clear, rational, and uniform standard for determining the extent to which a local educational agency is required to reassign and transport its students in order to eliminate the vestiges of a dual school system. (b) For the foregoing reasons, it is necessary and proper that the Congress, pursuant to the powers granted to it by the Constitution of the United States, specify appropriate remedies for the elimination of the vestiges of dual school systems, except that the provisions of this chapter are not intended to modify or diminish the authority of the courts of the United States to enforce fully the fifth and fourteenth amendments to the Constitution of the United States." 62 -15- In interpreting the Act less than one year after the AQ EEOA had been passed, the Sixth. Circuit in Brinkman v. Gilligan held that the Act did not limit either the nature or the scope of the remedy in a school desegregation case. The Court cited 11702(b) and emphasized the language regarding the Act not being intended to modify or diminish the authority of courts in desegregation cases. Referring to a prior decision ordering desegregation under the constitution, the court stated, "The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 19 74 by its terms does not prevent the District Court from 64 carrying into effect the previous mandate of this court." This, however, far from settled the broader question of the Acts co-extensiveness with the constitution. When the Sixth Circuit was faced with the broader question 65 m United States v. School District of Ferndale, the Court held that provisions of the Act must be interpreted independently as they come into controversy on a case by case basis. "There is unquestionably considerable overlap between these protections, and those provided under the fourteenth amendment. The statute does not expressly incorporate the amendment, however, and we are not prepared to say that the two provisions are co-extensive...We think it best to defer interpretation of any particular EEOA provision until the meaning of that provision is at issue in case before us."6® This judicially conservative approach seems to have been correct In light of the dicotomy in answers given to the coextensive question in different cases. 6 7 68 In United States v. Hinds County, School Board, the Fifth Circuit recognized that the EEOA created new substantive rights in the area of sex-segregation. The Court found illegal the recommendation by a federal district judge that a county school district be permitted to maintain a sex-segregated student assignment plan. Citing the congressional declaration of policy in §1702(a) (1), the court stated, "This declaration expressly goes beyond the rights guaranteed to school children under the Fourteenth Amendment prior to the EEOA's adoption and incorporates a judgment that a sex-segregated school district is a dual rather than a unitary school system and results in a similiar if not equivalant injury to school children as would occur if a racially segregated school system were imposed, (citations omitted)."69 The Fifth Circuit has also found the Act to go beyond the fourteenth amendment in the area of language impediments to education. 70 . 71 In Castaneda v. Pickard the court held 72 that §1703(f) required educational agencies to undertake appriate efforts to remedy the language deficiencies of it students, regardless whether the deficiencies 7 3 were caused by past segregation or intent to discriminate. The Castaneda Court, however, did hold that an intent to discriminate was a necessary element to establish claims under 74 §1703(d), which relates to discriminatory employment practices of the school district. Moreover, the court concluded "that discriminatory conduct proscribed by §17Q3(d) is coextensive with that prohibited by the fourteenth amendment and Title VI and does not encompass conduct which might violate Title VII because, although not motivated by racial factors, 7 5 it has a disparate Impact of persons of different races." The Court's holding that one provision of the EEOA goes beyond the fourteenth amendment while another provision is co-extensive with the amendment, is a clear indication that the Fifxh Circuit is 00530 engaging in the same type of case- by- case, provision - by provision interpretation of the EEOA utilized by Sixth Circuit. Turning specifically to the issue of MCTs with a diploma sanction, the question is whether §1703(b) is substantively the same as the fourteenth amendment as it relates to desegregation requirements. 16 point. Debra P. is the only circuit court decision in The Court summarily deals the plaintiff's claims under the EEOA after detailed examination of the constitutional claims. "Because the test perpetuates past discrimination... The diploma sanction violates the EEOA...which requires an educational agency to take affirmative steps to remove the vestiges 77 systems." of dual school The lack of any attempt to distinguish the pro- visions implies that they are substantively the same. Even better support for the position that §17Q3(b) is coextensive with the fourteenth amendment is found in the Fifth Circuit's holdings in bi-lingual education cases brought under the Act. As stated above, the Castaneda court distinguished §1703(f) from the rest of §1703 on the basis that §1703(f) did not contain language requiring a history of discrimination or present intent to discriminate. On the other hand, 1703(d) was held to require a finding of intent to discriminate in employment practices and to be co-extensive with both Title VI and the fourteenth amendment. The Fifth Circuit re-affirmed this 78 analysis In United States v. State of Texas. The Mexican- American plaintiffs brought a bi-lingual education suit under §170 3(f) and (b). The circuit court reversed the district court's mandate for state wide bi-lingual education under 170 3(f), because the issue was rendered moot, by the state's 00540 -18- enactment of new bi-lingual education programs. But, the court remanded on the issue whether other remedial orders were necessary on the grounds of past segregation under the fourteenth amendment and §1703(b). This is a strong indication that the court considered the provisions the same. In sum, because the Debra P. did not analytically distinguish the EEOA and constitutional claims, and because of the court's treatment of §170 3 in other cases, it seems that the Fifth Circuit considers 1703(b) to be co-extensive with the fourteenth amendment. Title VI Much litigation over the issue of the relationship of Title VI to the fourteenth amendment makes this question 79 less novel. Although some writers have argued that Title VI creates greater substantive rights than individuals have under the constitution, 80 that view is not supported by a 81 majority of the Supreme Court. As with the EEOA, the court in Debra P. did not distinguish the Title VI claims. It appears that Fifth Circuit considers it to be co-extensive with substantive rights and equitable remedies of the four82 teenth amendment. It is therefore unlikely that the claims under Title VI will be analyized in a manner distinct from the claims under the EEOA and the fourteenth amendment. The court in Castaneda held that actions violated the fourteenth amendment, the EEOA, and Title VI if they were taken with and intent to discriminate or they perpetuated the effects of past discrimination. The argument that discriminatory "effects" alone makes out a violation 00541 -19- 83 of Title VI was rejected by the Court. In light of a conclusion that the constitutional and statutory challenges to the MCT in Debra P. are the same, concepts of "vestiges" of a prior dual school system and remedies for their elimination become the focus of the analysis. Vestiges of a Dual School System and Remedies for Their Elimination As indicated in the section about desegregation under the equal protection clause, courts may hold a wide-range of school officials' acts and omissions to violate the constitution, when historic or present de jure segregation is found. The same acts and omissions of school officals will also constitute violations of the EEOA and Title VI, if one accepts the proposition that the statutory provisions are co-extensive with the fourteenth amendment. The question of the legality of the MCT exit requirement in a post desegregation setting, turns on whether the effects (vestiges) of the old dual system are perpetuated. If there is such a perpetuation the test is clearly illegal. Additionally, if vestiges of the dual school system become apparent in reviewing the use of the MCT, the court should exercise its equity powers to assure that school officials carry-out their affirmitive duty to remove such vestiges. Surprisingly little has been written on the subject of vestiges. The discussion in this section is an attempt to elucidate the concept. Looking beyond overt segregation of students by race, tangible equal protection violations can be found in "policies regarding faculty, staff, transportation, extracurricular activities, and facilities.... If it is possible to identify a school as a white school or a black school by racial composition of faculty and staff, the quality of the school buildings or equipment, or the organization of sports activities, a prima . . 314. racxe case of an equal protection vxolatxon is established." qc This is not to say that if separate but equal facilities are used no equal protection violation exists. The Court in Brown 86 v. Board of Education expressly rejected the separate but equal doctrine in education. In fact, Brown holds that seperate is inherently unequal for intangible reasons. It is the individualized effects that the dual system has on students which constitutes the equal protection violation. Despite the Supreme Court's recognition that harm caused by dual school systems was an intangible harm to individuals, the Court did not directly address the question of remedial education programs until it decided Milliken v. Bradley (II). As part of a comprehensive desegregation decree, the district court ordered programs established in the areas of reading, in-service teacher training,testing, and counseling. The Supreme Court affirmed the decision stating that it was based on substantial evidence in the record. The Supreme Court quoted the Sixth Circuit which said, "We agree with the District Court that the reading and counseling programs are essential to the effort to combat the effects of segregation.... Without the reading and counseling components, black students might be deprived of the motivation and achievement levels which the desegregation remedy is designed to accomplish." -21- 00543 87 The Court found these programs consistent with equitable principles which require (1) desegregation remedies be inaccordance with the nature and scope of the constitutional violation; (2) decrees to be remedial in nature so that victims of discriminatory action as nearly as possible will occupy the position they would have in the absence of such action; (3) taking account, consistent with the constitution, the interests of local authorities in managing their own affairs. 89 In Plaquemines Parish School Board v. United States, the Fifth Circuit upheld remedial programs in a desegregation decree eight years before Milliken was decided. A freedom-of- choice plan allowed blacks to transfer to formerly all white schools. The Court said the remedial programs ordered by the district court were "an intregal part of a program for compensatory education to be provided Negro students who (had) long been disadvantaged by the inequities and discrimination inherent in 90 the dual school system." Again, the decision was based on equitable powers used in accordance with the record. In another case the Fifth Circuit has held, "The court has not merely the power but the duty to render a decree which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of 91the past as well as bar like discrimination in the future." In sum, these cases demonstrate that vestiges of a past dual school system may be manifest as present segregation inequality of facilities and programs, and intangible harm to individuals. Regardless of the nature of the vestige, the government wrongdoers have an affirmitive duty to eliminate it. The courts also have broad equity powers to oversee the 0ft544 school officials conduct toward this affirmitive duty. Conclusion - Debra P. on Remand As stated above, Florida will carry a heavy two-pronged burden in establishing the legality of its diploma sanction under the Fifth Circuit standard. First, the state must prove that the exam is a fair test of that which was taught in the public school system. Secondly, the state must prove the racially dispropartionate MCT results are not caused by vestiges of the past dual school system or, that the use of the exam is necessary to provide minority students better educational opportunities. Even if Florida meets the exam validation burden, based on its history of past de jure segregation, facially neutral tests that perpetuate the effects of past discrimination are illegal. 92 In McNeal v. Tate County School District, 93 the Fifth Circuit specifically applied this principle in the area of public school ability grouping. In that case a school district was using an ability grouping program that had the effect of segregating classrooms. The Court held that ability grouping per se is not constitutionally impermissible; but, in a post-desegregation setting school officials must "demonstrate that its assignment method is not based on the present results of past segregation or will remedy such results through better 9 4educational opportunities." In Debra P. the McNeal analysis seems to end with the question of vestiges. If the dispropor- tionately high MCT failure rate is attributable to some vestige of past illegal segregation, it is incomprehensible to view the denial of high school diplomas to the victims as providing them better educational opportunities. 9 5 00545- To rebut a presumption that the desparate impact the MCT has on minority students is a vestige of the past dual school system, Florida might attempt to offer alternative explanations for the minorities' high failure rate. In Parents in Action on 96 Special Education v. Hannon, a federal district court in Illinois upheld an I.Q. test used in disproportionately tracking minority students into classes for the mentally handicapped on the grounds that the exam was not culturally biased. The court accepted the argument that socio-economic factors related to environment interfere with the cognitive and intellectual 97 98 development of children. But, m another case involving the tracking of students for special education classes, a court expressly rejected this environmental argument and an argument that genetic differences might cause the disparate I.Q. test 99 results. Some sociological theory might be advanced to argue that certain minority subcultures do not hold educational achievement as a strong value and that poor MCT performance can be explained in terms of low motivation. Regardless of possible merit in any alternative explanations for minority students' poor academic development, this writer believes Florida is in a no win situation. To get to the question of vestiges Florida must show that the MCT is a fair test of what was taught in their school system. If the MCT is validated by that standard it is necessarily an exam coverning material that the students have successfully completed to get to the twelve grade. Apparently none of the theories for poor educational performance of minority students had worked against the students 00546- who attained the twelve grade status. When the diploma sanction exam is given at the end of the twelve grade the results are glaringly skewed against minority students. The obvious, question is how did these academically deficient students pass up through the system for eleven years and then flunk an exam which is a fair test of what they were taught. The Fifth Circuit standard of validating MCTs would seem to create an instrument for identifying students who have been socially promoted. Social promotion by itself may be lamentable; 10 0 but, it is not a constitutional or statutory violation. However, because of the discriminatory manner in which it occurs in this post segregation setting, equal protection and statutory rights are jeopordized. If a MCT is validated to the Fifth Circuit's standards and it shows minorities failing at disparate levels to whites, then unequal treatment of minority students is demonstrated. The Fifth Circuit held that there is no current invidious intent to discriminate on the part of Florida school authorities. Therefore, the unequal treatment of minority students that the valid MCT might demonstrate would a vestige of the old dual school system, rather than present racially intentional actions. However, finding unequal social promotions to to be a vestige of the old dual school system is sufficient for holding that equal protection, Title VI, and the EEOA have been violated. Because the effects (vestiges) of the dual system are perpetuated by the use of the MCT with a diploma sanction, in that students discriminated against will be further harmed, its use should be enjoined. Additionally, the equal protection clause 1 0 1 and the EEOA 1 0 2 both impose affirmitive duties on 00547- school officials to eliminate the vestiges of dual school systems. Ironically, that would probably mean ordering Florida to administer the MCT in some form to identify students who have been or might be socially promoted in order to give them 10 3 remedial assistance. Under the desegregation case law and 104 the EEOA the scope of the remedy should be limited to the extent of the constitutional violation. But, clearly action to stop discriminatory social promotion would be required. Finally, if the vestige is eliminated and peer group 10 5 equality is achieved between students of different races, there would no longer be a viable constitutional challenge to the passage of a valid MCT as a requisite for receiving a high school diploma. 00548 -26- E N D N O T E S 1. Gallagher and Ramsbotham, Developing North Carolina's Competency Program, 9 Sch. L. Bull. 1 (Oct. 1978). 2. See McClung, Competency Testing Programs: Legal And Educational Issues, 47 Fordham L. Rev• 651 (1979). 3. Id. at 657. Ela. Stat. Ann. §232.246 (WestSupp. 1980). 5. 644- F.2d 397 (Fifth Cir. 1981); rehearing en banc denied, 654 F.2d 1079 (Fifth Cir. 1981). 6. See Brickell, Seven Key Notes on Minimum Competency Testing, 59 Phi Delta Kappan, 5 89 (1978). 7. Id. 8. See Board of Curators of the University of Missouri v. Horowitz, 435 U.S. 78 (1978). 9. Debra P. v. Turlington, 644 F.2d 397 (Fifth Cir. 1981) and Anderson v. Banks, 520 F. Supp. 472 (S.D. Georgia 1981), 540 F.Supp. 761 (S.D. Georgia 1982). 10. U.S. Const. Amend. XIV. 11. 42 U.S.C. 2000d. 12. 20 U.S.C. 1701 et seq. 13. U.S. Const. Amend. XIV. 14. See Baker and Wood, "Taking" A Constitutional Look At The State Bar Of Texas Proposal To Collect Interest On AttorneyClient Trust Funds 14 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 329 at 341-342. 15. See McNeal v. Tate County School District, 508 F.2d 1017 (Fifth Cir. 19 75). 16. Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976). 17. McNeal v. Tate County School District, 508 F.2d 1017 (Fifth Cir. 1975). 18. Id. 19. Laws of Florida 1976, Vol. 1, Ch. 76-223, pp. 489-508. 28- 20. Fla. Stat. Ann. §229 . 55( 2)(a), (d), (f). 21. Fla. Stat. Ann. §232 . 246(b). 22. The SSAT was administered in the fall of 19 7 7 and 19 7 8 and in the spring of 19 79. On the first occasion approximately 36% of the students flunked one or both sections. This group included 78% of all the black students who took the test, as compared to 25% of the white students tested. In 1978, 74% of the black students retaking the test failed one or both sections, as compared to 25% of the white students. After the test had been given three times, 20.049% of the black students had failed the test all three times, as compared to 1.9% of the white students. Debra P. v> Turlington, 474 F.Supp. 244, 248-49 (M.D.Fla. 1979). 23. Three classes were certified by the court: (1) all present and future twelfth grade public school students in the State of Florida who had failed or who thereafter failed the SSAT II. (2) all present and future twelfth grade black public school students in the State of Florida who had failed or who thereafter failed the SSAT II, and (3) all present and future twelfth grade black public school students in Hillsborough County, Florida, who had failed or who thereafter failed the SSAT II. 24. Debra P. v. Turlington, 474 F.Supp. 244 (M.D.Fla. 1979). 25. Debra P. v. Turlington, 6 44 F.2d 39 7 (Fifth Cir. 19 81). 26. This holding was based on the rationale that "the state need not correct all the problems of education in one fell swoop and it has a stronger interest in those (institutions) which it pays the cost." Id at 40 6-0 7. 27. This holding was an affirmance of the trial court without comment. But, the rationale is based on the standard of McNeal v. Tate County_School District, 508 F.2d 1017 (Fifth Cir. 1975), which is discussed in the text infra. 28. The district court judicially noted that de jure segregation of schools existed in Florida from 1885 to 1967. 474 F.Supp. at 250. On the basis of evidence presented and judicial notice of Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, Florida, 427 F.2d 874 (Fifth Cir. 1970)., the court found that blacks received unequal education from 1967-1971. Id. at 251. The court labeled the period from 19 71-19 79 the "transitional phase" and noted a "host of human problems." The court found that no remediation programs. 00550- of any kind were started until 1977, and the "effects of past purposeful segregation have not been erased or overcome." Id. at 252. 29 In order for a testing instrument to be scientifically valid the American Psychological Association requires: criterionrelated vality, content validity, and construct validity. For a detailed discussion of these concepts as they relate to MCTs, see McClung, Competency Testing Programs: Legal and Educational Issues, 47 Fordham L. Rev. 651, 683 (1979). The Fifth Circuit upheld the District Court finding that the exam was not culturally biased but found, based on the record, that a finding of content validity was clearly erroneous. 644 F.2d at 405. 30 Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973). 31 32 See note 28 supra. 33 Apparently, because the injunction was limited to the time it would take students who can attend segregated schools to complete their education (4 years). 474 F.Supp. at 269. 34 Taylor v. Ovachita Parish Schools, 648 F.2d 959 (1981). 35 United States v. Gregory - Portland Indep. School Dist., 654 F.2d 989 (1981). 36 See, e.g., Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976). 37 The Supreme Court in Pasadena City Board of Education v. Slangier, 427 U.S. 424 (1976), showed some acceptance of this view m holding that a school district's one time implementation of a "racially neutral attendance pattern" was to sufficient to releave it of the district court's continuing desegregation jurisdiction. Id. at 743-44. 38 443 U.S. 449 (1979). 39 443 U.S. 526 (1979). 40 Debra P. v. Turlington, 644 F.2d at 407. 41 347 U.S. 483 ( 1954) . 42 349 U.S. 294 (1955) 43 Id. at 301. 44 Nowak, Rotunda, and Young, Constitutional Law (19 78) at 56 5. 45 377 U.S. 218 (1964). 46 Id. at 234. 47 391 U.S. 4 30 (1968). 00551- 48. Id^ at 438-39. 49. Id. at 437-38. 50. 402 U.S. 1 (1971) 51. Id^ at 16. 52. Id. at 15. 53. 413 U.S. 189 (1973). 54. Id. at 205. 55. 418 U.S. 717 (1974). 56. IdL at 744. 57. 20 U.S.C. §1701 et. seq. 58. 20 U.S.C. §1712 addresses formulation of remedies under the Act: "In formulating a remedy for a denial of equal educational opportunity or a denial of the equal protection of the laws, a court, department, or agency of the United States shall seek or impose only such remedies as are essential to correct particular denials of equal educational opportunity or equal protection of the laws." 59 . 20 U.S.C. §1701. 60 . H.R . Rep. No. 13915 , 9 2d Cong. (19 72). 61. 120 Cong. Rec 62. 20 U.S.C. §1702. 63. 518 F.2d 8 53 (Sixth Cir. 19 75). 64. Id. at 8 56 H2161 (May, 1974). • 65 . 577 F.2d 1339 (1978). 66 . Id. at 1346. 67. See notes 52 and 54 infra and related text 68 . 560 F.2d 619 (1977). 69 . Id. at 62 3 • 70 . Castaneda v. Pickard, 658 F.2d 989 (1981). 71. Id. 00552- 72. The subsection provides: "No state shall deny equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race, color,, sex, or national origin, by - (f) the failure of a educational agency to take appxiate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional programs." 73. A consistent case is Martin Luther King Junior Elementary School Children v. Michigan, 473 F. Supp. 1371 (D.C. Mich. 19 79), which held that while 170 3(f) was not a vehicle to attack all the problems caused by poverty, students language impediments must be remedied by appriate steps, without regard to discriminatory intent. But, a contra view is found in Otero v. Mesa Co. Valley School District, 470 F.Supp. 326 (D.C. Colo. 1979), which hold §1703 to be co-^extensive with Title VI and the fourteenth amendment. Therefore intent to discriminate must be shown. 74. The subsection provides: "No state shall deny equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin, by - (d) discrimination by an educational agency on the basis of race, color, or national origin in the employment, employment conditions, or assignment to schools of its faculty or staff, except to fulfill the purposes of subsection (f) below;" 75. 648 F.2d at 1000 - 1001. 76 . 644 F.2d 39 7 ( 1981) . 77. Id. at 408. 78. 680 F.2d 356 (1982). 79. See e.g., Lee v. Conecuh County Board of Education, 634 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1981); Lee v. Washington County Board of Education 625 F.2d 1235 (5th Cir. 1980); Crawford v. Western Electric Co., Inc., 614 F.2d 1300 (5th Cir. 1980); Williams v. DeKalb County, 5 82 F.2d 2 (5th Cir. 19 78). 80. See e.g., Benjes, The Legality of Minimum Competency Test Programs Under Title VI of The Civil Rights Act of 19 64, 15 Harv. C.R. - C.L.L. Rev. 1980). 81. See Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). 82. Castandeda v. Pickard, 648 F.2d 989 (1981). 6 2 and 6 3 for more cases. 83. Id. 00553- See also notes 84 Nowak, Rotunda, and Young, Constitutional Law (19 78) at 578, citing, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 18 (1971). 85 See Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). 86 347 U.S. 483 (1954). 87 433 U.S. 267 ( 19 77) . 88 Id. at 278. 89 415 F.2d 817 (1969). 90 Id. at 831. 91 Felder v. Harnett Co. Board of Education, 409 F.2d 1070, 1074 (Fourth Cir. 1969). Many Fifth Circuit desegregation cases have recognized the affirmitive duty to eliminate vestiges of a dual school in formulating their remedies: Tabsy v. Concerned Citizens of Glenview, 572 F.2d 1010 (1978); Northcross V. Board of Education of Memphis City Schools, 466 F.2d 890 (197 2); Edgar et. al v. United States, 404 U.S. 1206 (1971); Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction of Bay Co. Fla., 430 F.2d 625 (1970). 92 Gaston v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969). 93 508 F.2d 1017 ( 1975) . 94 Id. at 1020. 95 For a recent position on the Supreme courts view of the importance of educational opportunities see, Plyler v. Doe, 10 2 Sup.Ct. 2382 (1982). 96 506 F. Supp. 831 (N.D. 111. 1980). 97 Id. at 878. 98 Larry P. v. Riles, 495 F. Supp. 926 (N.D.Cal. 1979). 99 Id. at 955-56. 100 Without a suspect class or fundemental right involved, state actions are constitutional if not irrational (equal protection standard) or arbitrary (due process standard). The state action also has the benefit of a presumption of constitutionality. 101, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklengurg Board of Education, 40 2 U.S. 1 (1971). 10 2. 20 U.S.C. 1703(b). 00554- 103. Milliken v. Bradley (II), 433 U.S. 267 (1977). 104. 20 U.S.C. 1712. 105. McNeal v. Tate County School District, 508 F.2d 1017 (Fifth Cir. 1975). 00555-