97 WHALES AS M ENDANGERED S P E C I... JAN MARTIN

advertisement

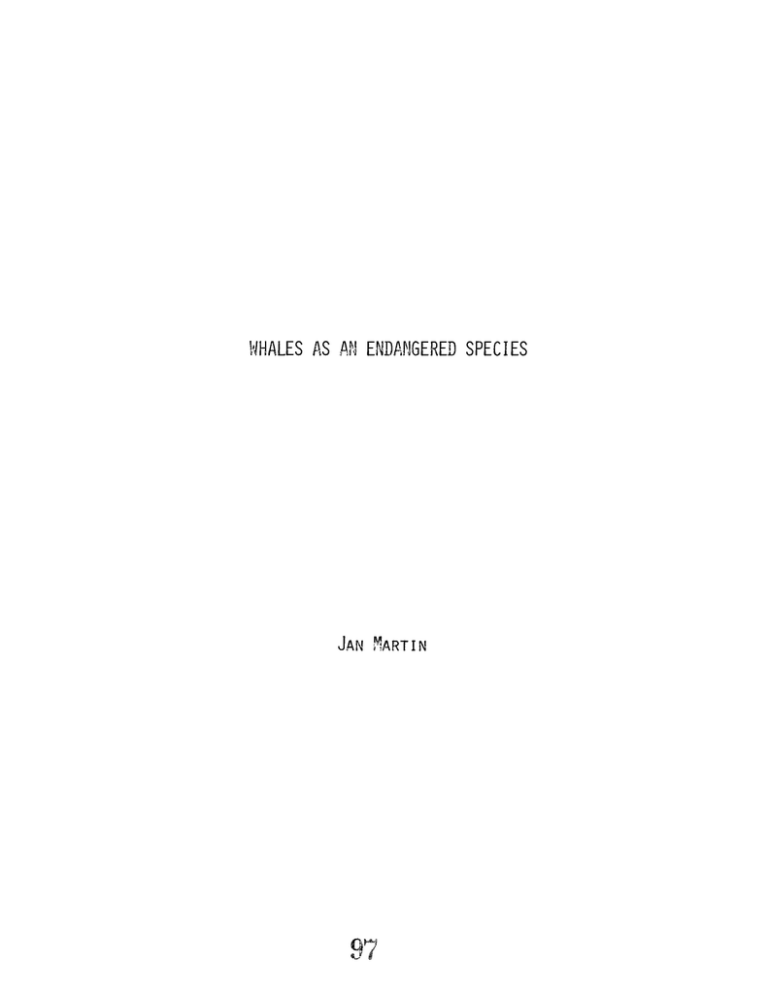

WHALES AS M JAN ENDANGERED MARTIN 97 SPECIES WHALES AS AN ENDANGERED SPECIES BY JAN MARTIN Submitted to Professor Frank E. Skillern Texas Tech School of Law January 9, 1978 WHALES AS AN ENDANGERED SPECIES Introduction I. The Whale Classification Feeding Habits and Migration Recruitment II. Whaling History Technological Development Japan's Role Need for Regulation I'll. Whaling Regulation 1931 Convention for the Regulation of Whaling Blue Whale Unit 19^6 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling International Whaling Commission Federal Statutes IV. Other Considerations Economic Costs of Whaling Minimization of Harm and Ecology Conclusion 99 WHALES AS AN ENDANGERED SPECIES So little is known of the whale that it is difficult to be certain of many things. Greater knowledge is possessed by man now than ever before, yet in relation to knowledge of other animals it is comparatively little. Many conferences have been held on the regulation of whaling and there are two international conventions in force, not to mention several Federal statutes. The study of whales and whaling unfolds multiple aspects of the problems which go hand in hand with any attempt at conservation of whales or regulation of whaling. 1. The Whale According to scientific nomenclature whales cannot be correctly termed an endangered species because whales are part of the Order Cetacea. Nonetheless, there are eight species of whales listed as endangered in the Federal 2 . 3 Register as ordered by the Endangered Species Act of 1973. including the Blue Whale, Bowhead Whale, Fin Whale, Gray Whale, Humpback Whale, Right Whale, Sei Whale and Sperm Ll Whale. The fact that these great whales are included on this list means that neither the animals nor their products may be imported into the United States.J McVay defines an endangered species by stating "a species is endangered when the exploitation rate is so 100 2 high that, on the average over time, each adult less than 6 replaces itself in the next generation." The above listed animals have been subjected to such exploitation. These whales are commonly known as the great whales or larger Cetaceans and have been the basis of the international whaling industry. Cetaceans are mammals, though often referred to as fish by whalers/'7 The order is divided into two distinct suborders, Mystacoeti and Odontoceti. The seven whales listed above besides the sperm whale all fall into the first suborder and are known as baleen whales. Suborder Odontoceti encompass sperm whales, porpoises and dolphins, members of this group are known as toothed whales. In the Suborder Mystacoeti the whales 8 of the family Balaenopteridae are referred as rorquals, and are characterized by the grooves running from the lower lip to the chest. The blue whale, fin whale, sei whale and. the humpback fall into this category. The blue whale has been named the mainstay of whaling because it is the largest of the whales, yielding more profit for whalers. Little is known of whales as compared to other marine mammals due to the difficulty of intense research. The amount of and type of food in addition to their size makes it impossible to keep a great whale m captivity for study. Sperm whales feed mainly on squid which is one reason they spend most of their lives in tropical seas. abundant where cool and warm waters meet. Squid are Baleen whales possess plates of whalebone instead of teeth limiting their diet to small sea animals-, i ankton. and phytoplankton, 10 which can be swallowed without chewing. A major part of their diet' consists of krill, small crustaceans. Diet in part controls the migration of baleen whales. The summer months are spent in polar waters, feeding, the whales migrating before the ice pack expands and cuts off the open sea and food supply. The whales travel toward 11 warm waters for mating or to give birth. Krill is abundant in cold water due to the abundance of carbon dioxide, oxygen and other inorganic nutrients which nourish diatoms. Diatoms are small plants on which 12 krill feed. Damage to the environment is a result when a food chain is severely disrupted, but the probabilty and nature of the damage remains unknown. A species of whale will separate into stocks. is a group within which whales live and breed. A stock A species can be termed a group potentially able to interbreed, but a stock is a population unto itself. ically and behaviorially seperate. Stocks are geograph- For example, a stock of blue whales migrates to the Arctic and another migrates to the Antarctic during the summer. seasons between the13hemispheres Due to the difference in these whales will probably never intermingle.x Baleen whales are found in groups of mixed sex while sperm whales are found in polygamous groups of one male and about ten females. Among baleen whales the sise difference between male and female whales is minimal making it useless to set quotas by sex, however, female sperm whales are often ten feet or more shorter than males, making it possible to set quotas by sex. ' Consequently, males without harems can be killed without affecting the recruitment rate drastically (in theory). Recruitment is "the quantity natrually added to the stock each year to build it up to replace what has been lost through natural deaths or catching" while "sustainable yield is ... the catch which can be taken without affecting 15 the level of the stock." J The rate at which stocks reproduce is a major factor in deciding whether a stock or a species dies out. Two principles apply theoretically to the relationship between population size and recruitment. The first is a tendency for the recruitment rate to increase as population size decreases, making-up for the loss. However, the second principle refers to a critical population level. At this level the recruitment rate ceases to increase as the population becomes smaller? when a population reaches this level extinction is inevitable. Each species has a different critical population level, whether several hundred or thousand. II. Whaling Aside from several major developments, the factory ship in 1905. and harpoon with the exploding head in the 1860's, the whaling industry has not undergone a great 17 number of changes since its beginning. The Basques began whaling from land bases in small boats during the twelfth century. The right whale was the first target because 103 its migration route is along the European coast and it is a slow swimmer. By the fifteenth century they had built 18 larger ships and pelagic whaling began. Although Arctic whaling during the early seventeenth century was known as 19 the Golden Age of Whaling, y the discovery of Antarctic stocks produced the largest catches ever. Whaling in the United States began in the seventeenth century? early whalers also exploited the right whale. The value of sperm whales was 20 discovered in 17-12, providing stimulation to the industry. Americans As the Basques, the killed the whale which was the easiest to kill first then moved to the open seas. The sperm whale became the support of the American industry which virtually ended ?1 in 1925s ~ though Eskimos continue whaling. Rorquals became significant in the twentieth century due to advanced technology. Whalers long knew about them but they swam faster than ships could sail and sank when killed. The development of the steam powered catcher boats, harpoons with expd^liding heads fired from cannons,.^and„a method of filling the carcass^With air to float themAntarctic made it possible to comercially market rorquals. 22 The was a virtually untouched source of rorquals in the early 23 years of this century. J Rorquals could always be found during the Antarctic summer because of their food supply requirements. For the whaling season of 1913-1^ "the Antarctic catch was eighty percent of the world catch and more than three times the world catch ten years before. Whale oil production peaked in 1931 but, the largest amd most profitable whales had been overfished? an increased catch never produc 2k- as much marketable product. The Japanese also have a whaling history. Like the Basques and New England whalers they were able to operate a land based industry by killing gray whales and others that passed close to shore. In the seventeenth century they 25 developed large nets to catch whales. In modern whaling Japan takes a large share of the established quotas. As countries like Great Britain and Norway decreased their fleets' size and later ceased whaling, Japan bought their ships and a share of their quotas. Using these quotas plus its own, Japan has been able to maintain a 2 larger 6 catch and still remain within agreed regulation. As the Antarctic stocks dwindled, the North Pacific regained some importance as a whaling ground. A special meeting was called in 1966 for the nations involved, including Japan, Canada, U.S.S.R. and the United States. Canada and the United States were involved because of the 27 whaling done by Indians and Eskimos. The urgent need for stringent regulations is exhibited by a few facts. The bowhead, right and gray whales were over exploited before and during the ninteenth century; the blue whale whale has almost been wiped out. If we term the existing whale stocks as the principal, a certain number of whales can be harvested without depleting the population; this harvest can be termed interest. While the principal is undisturbed interest will be produced, 105 -2?but if both the interest and principal are used the resource will become depleted and extinct. , the principal. Regulation should preserve 28 III. Whaling Regulation If whaling had remained based in land stations, regulation would be most effective through individual nations, but whaling is pelagic and international regulation is the 29 most effective means of controlling pelagic whaling. Though the international community had recognized the 30 need for strict regulation the Convention for the Regulation of Whaling of 1931 was virtually useless. The limitations set were too vague, also the nations offered only limited protection to the almost extinct right whale and bowhead whale. "Additionally, the convention is internationally uneforceable due to the failure of Japan and the U.S.S.R. to accept it. As of January 1, 1976, there were 32 forty-seven nations as signatories to the 1931 Convention.No matter how weak the 1931 Convention is, it was a first step. In 1937 the International Agreement for the Regulation of Whaling was signed containing regulations limiting the season, placing a minimum length on blue whales, 33 AACL limiting the area permissively subject to pelagic whaling. Two conferences were held in 1938 and 1939 prescribing more regulations; one was planned for 1940 but World War II cancelled it and precluded further efforts until 1944.Before World War II and throughout the 1930's Japan remained uncooperative. 35 I /CO -S-The first attempted regulation after World "War II was instigated by the British in 1944. It was at this conference that the blue whale unit was established as the standard for quotas in the Antarctic region (south 40° S. latitude). The quota set was 16,000 b.w.u.. One b.w.u. equals onn blue whale, two fin whales, two and one-half humpbacks or six sei whales. Based on oil yield the system has proved scientifically unsound. It was hoped that whalers v/ould divide their catch among the different species but this did not occur. The 16,000 b.w.u. quota was too high and as always the whalers hunted the blue and humpback whales 3? first to obtain the highest yield with the least effort. The United States called the next conference in 1946. The result of this conference was the International Convention for the Regulation of o Q Whaling and the International Whaling Commission or IWC. " Fourteen nations represented themselves at the conference; Japan was represented by Allied Observer Officers. Several countries later subscribed to the 1946 Convention including: Iceland, Sweden, Mexico, Panama and Japan. Several countries have since withdrawn including: Chile and Peru. Chile and Peru then combined 40 with Ecuador to form the Commission for the South Pacific. As of January 1, 1976 there were fifteen nations listed 4l as parties to the Convention. The 1946 Convention has only been ammended once since 1946, in November, 1956. The purpose was to extend regulation to aircraft, helicopters, and to make methods of inspection 42 among the ammendable provisions of the Schedule. 107 -17The Preamble to the 1946 Convention sets the tone for the Convention's interpretation; it is in the Preamble il o that conflict first arises. J The Convention speaks of whales as a natural resource that should be protected in the second paragraph of the Preamble. The words "conservation" and "preservation" are present throughout, but in the last paragraph, the preamble states conservation is desireable to "make possible the orderly development of the whaling industry." J The whaling industry has main- tained an active interest in the activities of the IWC, established in Article III of the Convention. The IWC is to encourage studies of whales and whaling, collect data on whale stocks, study information on population 46 maintenance, and make reports of its activities. The 1946 Convention has a second part known as the Schedule; it contains the regulatory provisions. The Schedule can be ammended by a three-fourths majority vote of the IWC. This procedure makes it unnecessary to make new formal agreements in the event of needed changes. Any subscribing nation has ninety days to object to a proposed ammendment; if an objection is made the resulting regulation will not apply to that government. In case of an objection there is an additional ninety days granted to other nations for further objections. A government which previously agreed 49 to the provision is free to object at a later time. y This is an effective means of regulation only for those who want it. The IWC has no powers of enforcement. the schedule and its regulation^. i^tt has no It can change power if a 47 ' 48 -10K0 state decides not to agree to an ammendment^ and objects. Aside from the problems within the 1946 Convention, many governments do not grant unconditional authority to the head of the delegation to the IWC. This increases the pass- ibiltiy of an objection after the commission has adjourned. 1 The IWC meets in June each year and has three permanent committees, Finance and Administration; Scientific, and Technical. Presently a cetologist serves as Executive Secretary, a change from the part-time administrator of the past. 52 Although the IWC has no autonomy and can only c-1 carry out the wishes of member nations, J it has made progress toward whale conservation. A few examples of regulations include size limits for catching; the setting of dates for the whaling season, and a ban on killing certain 54 . . . species. Yet conflict remains, Article V, paragraph one of the convention authorizes the IWC to ammend the Schedule defining the type of regulations, while paragraph two restricts this power in part by not allowing any limit on the number of factory ships or land stations per country and by specificially giving the whaling industry consideration on every ammendment. Since the IWC has the power to make regulations but no power of enforcement, why should a nation bother to be concerned? regulations- Certainly there will be infractions of the One example involves the role of the inspector on Japanese whaling vessels. The position was so honored that the inspector did not come on deck during the flensing (butchering of the carcass). the needed The workers took -10measurements, having no reason to be unbiased, the measurements were probably inaccurate. Impartial observers are needed There are ways of loosening the restrictions such as filing an objection or withdrawing from the Convention^ <7 states have used both methods. However, the fact that the IWC cannot impose sanctions against those who violate the Convention does not mean that a country will purposely violate the Convention. There are many factors which cause a state to abide by the law even in the face>of temptation to violate it; a strong expectation of resulting advantages is ordinarily necessary for a state to violate the international norm. Under the Convention (19^6) each subscribing nation is expected to enforce the regulations in regard to its citizens, plus fulfill the responsibilities necessary 59 to maintain international supervision and enforcement. Nations frequently find it more advantageous to carry out their responsibilities for several reasons. Observation of law can be a valuable instrument of foreign policy,^°but the responsibility of enforcement can become a heavy burden. A nation can insure primary representation of its whaling industry by choosing a delegate to the IWC who is £? a member of the whaling association of said country. In the past economic considerations have been given too much weight in setting the quotas; one reason for this is the whaling industry representation at the IWC meetings. The quota for the Antarctic blue whale should never have exceeded 1 1 0 -12} J 3,000 b.w.u.j the animal was overfished in 1946. 6' , t , Yet, fjli , the 19^9 quota of 16, 000'b.w.u. was maintained until 1953. By 1956 the quota was reduced to 14,500'b.w.u. which was still too high. The IWC8s authority over quotas is restricted to a cumulative or "global quota", having no authority to allocate the quota between nations. Ordinarily, the interested nations meet to divide up the quota decided upon, after the IWC meeting each year,^t the smaller the stocks become, the harder it is to fill a quota. To make a profit it is necessary to get a large catch; therefore, the goal of Antarctic whalers has?to capture as many whales as possible as quickly as possible. Antarctic whaling 66 became known as "The Whaling Olympic." The IWC has had a hard task in trying to preserve whales while trying to maintain the subscribing nations' interest through continued profits from whaling. In 1959 Norway and the Netherlands withdrew from the convention. Crippled, because Norway and the Netherlands were still major whaling nations, the IWC did not set a formal quota for the 1959-60 season. for the In stocks. 1960-61 I960 and In fact catch limits were suspended 1 9 6 1 - 6 2 seasons.67 three scientists were appointed to study whale The major whaling nations agreed to abide by the committee's recommendations by 1964. In 1963 the committee recommended that the blue whale unit be abolished in favor of quotas set by species, and that a ban on the killing of blue and humpback whales be instituted. The permanent scientific committee supported the special committee, but the recommendations were rejected in 1 9 6 3 and inll964.68 -13The 1964 meeting has been termed "disastrous" by J. L. McHugh. Again, nations were unwilling to adopt the type of quota necessary to preserve whales; no limit was set for the 1964-65 season. The whaling nations met after the commission meeting and set a quota of 8,000 b.w.u.. y And in 1964 Japan and other nations objected to protection for the Antarctic blue whale. During the 1960's many nations wanted to implement the International Observer 70 Scheme. The Convention of 1946 had been ammendea in 1956 to allow this,^ but implementation was delayed?2 The blue whale received complete protection in 1965In 1966 the Antarctic quota was reduced to 3.500 b.w.u. In 1971 the IWC agreed to abolish the blue whale unit for 1972 and the International Observer Scheme was implemented. 73 There -was a need impartial observers in order to obtain 74 objective data. The benefit of this plan is that the observer is not from the country whose fleet he is observing. 75 And, the observers report directly to the commission'-' By 1975 catch levels had been established for all oceans, and sperm whales were receiving special attention. The commission also provided76for more research on behavior and breeding of all whales. The sperm whale had not been included in the blue whale quota system for two reasons. First, sperm oil and whale oil (from baleen whales) aretotally different and cannot be used for the same things. Second, few sperm whales are found in the Antarctic. The blue whale unit was based on whale oil producing capacity 77 of whales in the Antarctic, mainly rorquals. In 1973 the United Nations Governing Council for Environmental' Programs confirmed a resolution for a moratorium on the killing of whales. The resolution was rejected at no the next IWC meeting* and the United States protested. The U. S. had been working for a 10 year moratorium through the IWC.79 Instead of a total moratorium, the Austrailian Ammendment was introduced in -1975 and vVe a v ».»* « *approved >& v* e sv'V by the commission. McKugh feels that ,—s considers the uncertainties of precise estimation the sustainable yield a whale On stock and is practical of but with the effect of aof moratorium. Under the plan a zero quota is assigned to stocks whose population is ten percent or more below the maximum sustainable yield. 81 Maximum Sustainable Yield is the largest number of animals which can be caught without any further depletion 82 of the stock. Under this new plan the permanent Scientific Committee determines the status of a stock and the quota. The effect is protection of endangered species and limited hunting.^ The United States has maintained an interest in whales despite the absence of commercial whaling as an industry in the U. S. Interest is manifest by continued participation 84 in the IWC. There are two strategies which have been used by the U. S. to further whale conservation on a international level. The first is a threat to invoke the Pelly Ammendment to the Fisherman's Protective Act 1967r of The effect of which would be a ban on importation of fish products from offending nations. 113 The second -2?is to arouse public opinion and private boycotts of Soviet 8 and Japanese goods. Japan and the U.S.S.R. are presently 86 the two major whaling nations. The U.S. implemented the International Convention for the Regulation of whaling on a national scale with the a n Regulation of Whaling Act of 194-9. The act provides for appointment of the U. S. commissioner to the IWC; 88 the commissioner receives no compensation. ' The act also authorises the Secretary of State in connection with the Secretary of Commerce to make or 89 withdraw any objections to ammendments to the Schedule. y Violation of IWC regu- lations is made illegal and licenses and license fees are required for any whaling operation. 90 The penalty for violation of the Convention is a fine of $10,000, or 91 imprisonment or both. The effect of this statute Is to institute international regulations on a national level. The Endangered Species Act should be interpreted as preventive, it shov/s that Congress is not willing to 92 wait for a species to become extinct before taking action.' A species' status is made public through the direction to the Secretary of the Interior to list all species which are endangered of threatened m the Federal Register. This listing is important because the act prohibits trade 94 in the whales listed. This trade limitation can operate as a sanction for Japan*, until 1970 when the list was I /CO first published under the 19&9 ac "t the U. S. was importin 9 r> a .large amount of whale meat every year. ^ The act is directed towards conservation of those species nearing extinction because there lies the urgent need Eskimos and Indians subject to Federal jurisdiction are exempt from regulation where whaling is critical to food supply and the economy, for example where 97 the whale is also used in the making of native articles. Under this act, two types of penalties may be levied against the violator. If the act is knowingly violated in the course of a commercial activity there is a civil penalty, but if a person willfully commits an act in violation of the act a criminal penalty will be assessed, consisting 98 of a fine, a year in prison or both. 7 The use of the word threatened allows regulation and preservation before 99 the species . . . is in immediate danger of extinction. 7 This is important when one considers the length of time it has taken to regulate whaling in a way that gives hope of the whale's survival. In the last section of the Endangered Species Act of 1973. the statute grants the Marine Mammal Protection Act precedence in the event of any conflict between the the two. 1 0 0 The Marine101 Mammal Protection Act took effect in December, 1972. Congressional intent seems to have been aimed toward protecting marine mammals before L . . they are nolonger a working part of their ecosytem. 1 0 2 This recognition of the need for early regulation and 115 -17of the importance of the ecosystem are just two examples of the importance of this act. There is also a recognized need for greater knowledge of whales as well as recognition of marine mammals as 103 a great recreational, esthetic and economic resource. A moratorium on the taking or importation of any marine mammal or marine mammal product is established and exceptions made are made according to scientific need or time needed to adjust to the fact that marine mammalsi nix will no longer be a source of revenue, commercially. The moratorium does not apply to Indians, Aleuts or Eskimos on the coast of the North Pacific or Arctic Ocean, if the whale is used for food or authentic handcrafts; however, the secretary is granted the authority by the act to impose regulations if a species used by the Eskimos or Indians becomes depleted. This is the case with the bowhead whale, it seems that at the 1977 IWC meeting all bowhead hunting was banned for 1978« But, the Eskimos claim a great need for hunting the bowhead. They won a court order in October of 1977 exempting them from the ban, but this decision was overturned on appeal by the U. S. Court of Appeals. The appellate court reasoned that exempting Eskimos would damage the United States' efforts at conservation. The Administration stated that it would ask the IWC at a meeting held in December, 1977 for permission 107 for the Eskimos to kill a limited number of bowheads. The question is, are there enough bowheads to allow for any 116 -10more killing or will the continued hunting result in a critical population level and extinction for the bowhead? Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, factors which must be considered by the secretary when making regulations include population levels, international agreements, and 1 OR the marine ecosystem. The secretary is required to propose such ammendments through the Secretary of State as necessary to make any existing treaty for marine mammal 109 protection conform to this statute. 7 Though until the treaty in question is changed, the provisions of the Marine Mammal Protection Act are in addition to, not in contravention of the treaty and statute implementing the treaty, in this case it is the 1946 Convention and the Regulation of Whaling Act.."'"''"0 The act also establishes the Marine Mammal Commission whose duties include reviewing of U. S. activities in relation to the 1946 Convention; making recommendations and reports and doing studies. Unlike the commissioner to the IWC, members of this , . 111 commission are compensated. Under the Pelly Ammend to the Fisherman's Protective Act of 1967, 112 the President of the United States is authorized to prohibit importation of any or all fish products from a country who conducts fishing operations in a way 113 which damages an international• fishery conservation program. Under the amrnendment, an "international fishery conservation program means any ban, restriction...pursuant to a multilateral agreement to which the United States is -2?a signatory party, the purpose of which is to protect the 1l4 living resources of the sea." The sole application of the Pelly Ammendment up until 1975 has been to whales. Japan and the U.S.S.R. both exceeded the minke whale quota in 1973-74, but since both countries supported the 1974 IWC quotas the President chose not to enforce the sanction.*^ The most current statute applicable to whales is the Whale Conservation and Management Act passed in October, 1.976. * ^ Congress imposed, a two hundred nautical mile or boundary for conservation of whales as Imposed in the 117 Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976. A need is expressed for protection within the two hundred lip mile boundary and for further study of whales. To fulfill the charges made by this act $1,000,000 was appropriated for 119 use in 1978 and 1979• One reason economic sanctions imposed by Federal lav/ are potuU effective against Japan is her "self development" program instituted in 1970. 1 2 0 Japan imported 99-7% of her petroleum and 88% of her iron ore in 1972. Japan also imports much 121 of her food. ~ The self development concept applies to Japan's dependence on trade and economic development needs. She wants to exert control over foreign resources through investments and to do this, will antagonze resource-rich countries. 122 not intentionally I /CO -21IV. Other Considerations The costs of whaling are tremendous. In the 1950*s a factory ship cost at least $11,000,000 and each catcher had a cost of approximately $600,000. useful for anyother purpose. These ships are not Whaling nations have tried to adapt the ships, but the attempts were impractical and unprofitable. To make a profit, whalers feel the need to maximize production by killing more whales. 123 The need for better catches causes larger expenditures 124 which enforces the need for larger catches. ' The effect is cyclical, but the larger whales are protected, shifting whaling emphasis to smaller whales. A greater number of small animals is necessary to equal the product yield of larger animals which when added to the cost of maintaining a whaling fleet begins the cycle. Japan maximizes production by using whale meat for human consumption. In the past the Japanese have been able to earn more than twice as much for meat alone 1 as a European country made for the entire whale. 126 There is no market for whale meat in Europe. This utilization has enabled Japan to continue whaling at a profit. 127 Since the harm to whales has already been done, at this point the hope should be that nations i O Q will minimize existing damage by causing no new harm. One positive step that should be taken is the step toward greater emphasis on ecological considerations and how the whale 119 -21fits within its environment. It has been said that ecology 129 is the answer of whale stocks. Ecological research on whales is especially difficult because of the vastness of their habitat ani the extent of their migrations. One example is the relationship between blue whales and smaller rorquals. The exploitation of blue whales increased the food supply causing a slight increase in numbers of less exploited rorquals. And, as blue whale hunting became more commercially unprofitable attention was turned toward the smaller whales, reducing their 131 numbers. The effect of this reduction is unknown. The lack of knowledge of whales is always detrimental to successful conservation. Though the primary responsibility for enforcing the . . . 132 IWC regulations rests with the mdiviual nations. " A less state centered perspective is needed in considering 133 the international law relating to whaling. ^^ Conclusion Truly there are a number of serious problems surrounding whales. Many species are close to extinction, some may have already reached their critical population level. There is a sore need for greater knowledge in all areas of the whale's existence. merits even more attention. But, the ecological area Man must consider the effect of the whale's extermination on the world's environment. 120 REFERENCES 1. R. Burton, The Life and Death of Whales 13 (1973). 2. 39 Fed. Reg. 1172,1174 (1974). 3. 16 u.S.C.A. 1533(c)(1), (1974) . 4. 39 5> McVay, "Reflections on the Management of Whaling," Fed. Reg. 1174. in The Whale Problem 378 (W. E. Schevill ed. 1974). 6. Id. at 379- 7. Burton at 14. 8. J. Cousteau and P. Diole, The Whale: Mighty Monarch of the Sea 262, 266-6?, 264~fT972TT 9- Fur ton at 2.0-21. 10. Scarff, "The International Management of Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises: An Interdisciplinary Assessment," 6 Ecology L. Q. 323,334 (1977). 11. Burton at 12. E.J. Slijper, Whales and Dolphins 107 (1976). 13. Scarff at 334-35- 14. Id. at 334. 15. K. R. Allen, "Recruitment to Whale Stocks," in The Whale Problem 3.52 (W. E. Schevill ed. 1974). 16. Id. at 354. 17. McVay at 372. 18. Cousteau and Diole at 281. 19 • Burton at 91• 20. Scarff at 345- 21. Cousteau and Diole at 281. 22. Scarff at 346. 23. Burton at l4l. 6O-61. -2?24. Scarff at 347- 25- Cousteau and Diole at 2 7 3 . 26. J. L. McHugh, "The Role and History of the International Whaling Commission, " 325 (W. E. Schevill ed. 1974) -frcw. 27. Id. at 329. 28. McVay at 375-376. 29- Tomasevich, International Agreements on Conservation of Marine Resources"2?2~(1971) . 30. Christol, Schmidhauser & Totten, "The Law and the Whale: Current Developments in the International Whaling Controversy," 8 Case W. Res. J. of Int'l L. 149 (1976) (hereinafter cited as Christol). 31. Convention for the Regulation of Whaling of 1931. art. IV, 1 5 5 L.N.T.S. 349; 49 Stat. 3079 (1934-35). 32. U. S. Department of State, Treaties in Force 444 (1976). 33. G. Small, The Blue Whale 172-74 (1971). 34. Scarff at 350. 35. Christol at 151. 36. Id. 37- Scarff at 352. 38. Id. at 352-53. 39. S. Oda, International Control of Sea Resources 79 40. Small at 1 7 8 . 41. U. S. Department of State, Treaties in Force 445 (1976). 42. Protocol to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling "signed under the date of Ded, 2, 1946," Nov. 1956, 338 U.N.T.S. 366 (hereinafter cited as Protocol to the International Whaling Convention). 43. Scarff at 353- 44. International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling with Schedule of Whaling Regulation, Dec. 2,1946, l6l U.N.T.S. 72 (hereinafter cited as IWC Convention). I /CO (1963) ^fJ6- ^Jirv -2?45 Id. at Preamble. 46 Id. at art. III. 4? Id. at art. 111(2). 48 McHugh at 315. 49 IWC Convention, art. V(3). 50 Ghristol at 153- 51 McHugh at 319. 52 Scarff at 355- 53 McHugh at 320. 54 McHugh at 306. 55 IWC Convention, art. V. 56 Small at 1 6 2 - 6 3 . 57 Scarff at 35?- 58 A. Sheikh, International Law and National Behavior 59 Scarff at 358. 60 Sheikh at 254. 6l Scarff at 357-58. 62 Christol at 153~54. 63 McHugh at 309. 64 Scarff at 360. 65. McHugh at 324. 66 Small at 91• 67. McHugh at 324. 68, Scarff at 3 6 2 - 6 5 . 69 McHugh at 326. 70. Scarff 71. Protocol to the Int'l Whaling Convention, art. II. 253-54 (1974TT at 365. I /CO -2?72 Scarff at 365. 73 Id. 74 McHugh at 330. 75 Scarff at 365- 76 Christol at l 6 l . 77 Small at 9 6 . 78 Christol at 1 5 6 . 79 Scarff at 368. 80 McHugh, Book Review, 3 Ocean Dev. & Int'l L. 389, 409 (1976) (hereinafter cited as McHugh, Book Review). 81 Friedman, "Legal Aspects of the International Whaling Controversy: Will Jonah Swallow the Whale/* 8 N.Y.U. J. Int'l L. & Pol. 211,223.(1975). 82 McVay at 376. 83 Friedman at 223-24. 84 McHugh, Book Review at 389. 85 Friedman at 222. 86 Christol at 1 6 3 . 87 16 U.S.C.A. 916-9161. (1974). 88 16 U.S.C.A. 916a. (1974). 89 16 U.S.C.A. 916b. (1974). 90 16 U.S.C.A. 916c & 9l6d. 91 16 U.S.C.A. 9l6f. (1974) :< 92 McVay at 379- 93 16 U.S.C.A. 1533(c)(1). (1974) 94, 16 U.S.C.A. 1538. (1974). 95. Friedman at 22?, n.84. 96, 16 U.S.C.A. 1531 - (1974). 97. 16 U.S.C.A. 1539- (1974). at 366-67. I /CO -2?98 16 U,S.C.A. 1540. (1974). 99 16 U.S.C.A. 1532. (1974). 100 16 U.S.C.A. 1543. (1974). 101 16 U.S.C.A. 1361-62,1371-84,1401-0?. (19?4). 102 16 U.S.C.A. 1361(2). (1974). 103 1.6 U.S.C.A. 1361 (3), (6) . (1974). 104 16 U.S.C.A. 1371. (1974) 105 16 U.S.C.A. 1371(b). (1974), 106 Gwyne & Cook, "Saving the Bowheads" in Newsweek, Nov. 7, 19?7 at 113- 10? Shabecoff, "Whale-Hunting Curb is Supported by U. in The New York Times, Oct. 21, 197? at 12, col.l. 108 16 U.S.C.A. 1373. (1974). 109 16 U.S.C.A. 1378. (1974). 110 16 U.S.C.A. 1383. (1974). 111 16 U.S.C.A. 1401-02. (1974). 112 22 U.S.C.A. 1978. (Supp. 1977)• 113 22 U.S.C.A. 1978(a). (Supp.1977). 114 22 U.S.C.A. 1978(g). (Supp. 1977)• 115 .Friedman at 232-33. 116 16 U.S.C.A. 9l?-91?d. (Supp. 197?) • 117 16 U.S.C.A. 917(3)• (Supp. 1977). 118 16 U.S.C.A. 917(5) & (?) - (Supp. 19??). 119 16 U.S.C.A. 9i?d. (Supp. 1977)• 120, Wells. "Japar and the United Nations Conference on on the Law of the Sea," 2 Ocean Dev. & Int'l L. 65 84 (1974). 121. Id. at 65. I /CO -2?122. Id. at 84. 123. Small at 82. 124. Id. at 93-94. 125. Id. at 134. 126. Id. at 102. 127. Id. at 134-36. 128. Stein, "Reeponsibilty and Liability For Harm to the Marine Environment," 6 Georgia J. Int' 1 & Comp. L. 4l, 45 (1976). 129. Friedman at 221. 130. Scarff at 412. 131. McVay at 378. 132. "New Perspectives on International Environmental Law," 82 Yale L.J. 1659,1678 (1973)• 133. Id. at 1659. I /CO APPENDIX A. Species Size and Distribution B. Shapes and Sizes C. Food Chain D. World Catch of Rorquals E. World Catch of Five Major Species of Whales F. Current Estimates of Whale Population Sizes If I':\!\:!<lc maximum iniclh Distribution CM o"r>n: C'ciacra : *.fy..'rVi-.'i:(\vlulcl',onc or baleen whales) r.'.rr.v Pafaemdae C ri cr..;.:* . rv^ht whale or bowheail ''\:i.:ct:j Arctic seas ca Go Cosnmp' litan except tr- pics ca 20 Antarctic seas ":,:ticclus) Go Pise.;v.-:: T b!. eh rirhf whale fEubjfwM /facialis) ••ipmv r-r.ht whale r''".' v (Carcrca n.r/iuaia) V.sth'ic'r.tiidae Grav \vh:.!e ca .15 North Pacific (Usciirichtiw /iH"sus) r;,."iLY Ealrairptcridiic (rorquals) n Elite whale (Br.!aa: pfra tnuscuhis) Fin whale phvsahts) Eei whale (]'.. nrrralis) : :"-.'c s wh; ! e l'. h'ydvi) i '.in/.c v.. :.'•: (V: c:uf->rv:r6ta) Ilinnrbaek whale (.'VC^.VM nevac-an/Jiac) or."::: (jdci-'cceii 'toothed v iiales) f : \ y v 107 Civ::u»politan Sj Cosmopolitan Go Cosmopolitan ca 50 Warmer seas ca i.i Cosmopi litan 50 Cosmopolitan r'nyincriuM r Sj cm. vhalv ( 'hyc!T ' male 60 , ,. iem,;, !e 40 (."nnorolitan ! ,-:nv Term whale ll^-'ia Wrictj*) ca i; Ovmopolitan ZrM'r /b.-Jutl whales) J'.-ird':; be:!:- 1 -h> 'TVvcW b.:i'dii) North Pacific Ar<.::c t-t-V.-.T.O'C whale 'h'v/rv drn >vnpn!l>tu<) ca 30 Arctic seas /,".:. :ct:c 1 ot:k:ic": whale III. pfamjrotis) 30 Antarctic seas r/.M'i.v Dr'p'iininac (dolphins) ! vjt wi-'*if '($' l"'rrpl:flhi wktcmi) ca 22 Cr "lopolitan r.-T.vr wl-v.lc '/Jrcmuf orca) 37 (. ••• m-ipolitan r.wccrkahis) r x L] eck-, t'v.-ir size am! <! 11 bnrinn. IV v r;- einn !)• «•' ::!:..have been : • <•! rer'-tuin t •> -.i:c mnn'"i'rs caufl.!. 'o prc?'cr ni.vinir*" 1C""t'-:- are ' • :. •. r rc:i- '!v in ! ::'-. !::i'w< • pecies. /.-. •: lerr.rhs i" wh: !cs ca'.'-.*!': are t.-.'rJ !-. . ..: oat V.'-C::IT ! ', !<->r the blue whale. Appendix A. Species Size and Distribution (Source: Burton at 18.) 128 •xmfte&ij »title Nome , Asian elephant tnajnm £Upk&i ous fsft *haj» Figure I S H A P E S AND S I Z E S OF SELECTED CETACEANS ipwrm ifem*J©j Pkytmltv ctttodon eotllrnoM-d doipfcm Cuner'» wfciu* Ztpkme asixerminu North Pae»f6f p&Ju boctteno* ^hftk arfe«t fith Appendix B. Shapes and Sizes (Source s Scarff at 3 3 1 ) . 129 Sunlight PhViiplrnkton: DLr.oms FI?3cllcrto3 Zooplnnkton*. Kri!l Opcpotlt Scc-tnr.tcrfiics Sq'irf r:h Tor.l'.r;' V.'iiclM V.'lT'-.tonci V.'hdos Appendix Ci Food Chain (Sources Burton at 50) 130 Appendix D. World Catch of Rorquals. (Source: McVay at 372). 131 Rev-ia i n d e r O R Ant a r c t i c SF*A r.nn a Blue? Fin HUT i p K v r k Sri Sperm Blue v-j M f'i n S0 i 1. 733 1, 413 1,049 741 651 720 67 0 817 Hurnfibick 1920 1921 1 , R74 2,617 261 3,213 71 8 400 284 260 5,491 36 31 370 34 3 I'lP? 4,416 9 2,492 103 3 859 1,15 3 '2, 192 3 5,08 3 517 3,677 10 1,462 3,0 4 6 1924 3,732 233 3,015 1925 5,703 359 002 23 1,1 8 6 193 66 1,113 973 3, 859 1 , 5? 6 4,366 1 59 1,845 2,983 4, 755 1,092 - SCOT. 576 888 es4 1,380 19?6 4,697 364 8,916 195 37 2, 2,674 5 , 34 8 1 ,299 1,54 5 1927 0,54 5 189 5,102 39 2,170 2,359 1,275 23 88 3 72 1 , 293 1,453 1,407 1,60- 1929 8 , 334 12,847 3, 5 0 6 2 , 594 1,219 1928 4,459 778 59 6,690 808 62 916 256 443 741 1,693 1930 17,898 05 3 11,614 216 73 1,181 1,066 2, 667 62 5 1 1931 29,410 576 10,017 145 51 239 206 1932 184 159 2,871 5,168 16 13 217 1933 6,488 18,891 1934 17,349 872 7,200 1935 16,500 1 965 12,500 530 52 65 2 107 171 0 666 177 1,417 577 334 2,123 266 2, 1, 571 60 679 83 915 29 43 3 468 541 1,176 578 696 1,6C1 721 4,44 : 746 6,126 2 r. ? 793 2,9.-:' 469 2 , 1 " 1936 17,731 3 162 9,C97 2 399 377 1,529 19 3 7 1 4 , 304 4 477 14,381 490 926 332 2,135 1938 14,92 3 2 079 28,003 161 867 112 3,046 1939 19-10 14,081 883 20,784 2,585 71 510 11,480 2 18,694 1,938 79 526 4 51 3,3 0 5 1/6 7 1 1,8 3 8 1,2 3 0 2 675 16 7,831 804 86 258 X, 109 21 339 0 776 73 24 26 277 1,158 197 101 14 261 ,666 78 45 69 85 393 273 1,431 2,622 4,078 2,727 69 110 22 81 19-11 4,943 194 2 194 3 59 125 1 94 4 339 1945 1,042 60 3,606 9,192 238 29 9,185 14,54 7 6,908 7,625 6 , 182 26 31 2 ,143 21,111 19,123 20,060 1952 1953 1954 1955 7,048 5,130 3,870 2,697 2,176 1 ,638 1 ,556 963 605 495 19,456 22,527 22,867 27,659 28,624 1956 1957 1958 1959 19C0 1,614 1,512 1,690 1,192 1 , 239 1 ,432 27,958 27,757 1 692 27,473 27,128 27,575 ,309 ,421 4 309 6,535 5,652 4 ,227 1961 1962 196 3 1964 1,744 1,118 947 718 309 270 28,761 5 102 5 196 112 20 2 4,800 4,829 4,771 6,711 4 ,352 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1551 1965 1966 1967 1963 1969 1970 1971 4 679 396 2 394 , 3 38 1 0 110 52 1,189 1 27,099 18,668 14,422 7,811 621 578 1 ,284 886 530 621 373 263 305 250 226 1 2,536 0 0 0 0 0 2,893 2,155 3,020 3,002 17 58 7 1 2 368 1 0 357 5 776 5 857 0 0 2,883 6 151 1 4 0 0 4,555 4,960 2,568 2,682 3,090 2,745 Appendix E. 433 5, 35) 1, 084 792 243 987 140 2 , 4 50 1,62 6 255 1 837 1 948 2 887 2 640 2 84 2 662 952 1,277 1,187 3 363 3 078 2 714 3 676 3 561 2,147 2,593 1,587 1,462 1 , 371 13,296 6,072 3 538 3 900 4 207 3 824 3 489 1,516 1,446 11,616 14,727 2 , 361 15,311 15,646 16,117 3,155 3 056 3 248 4 731 4 540 2,683 3, 608 4,046 4,995 5,074 16,330 18,497 23,087 4 •156 3 507 9 30 2 300 2 055 5,480 6,648 22,873 21,464 21,512 21,455 22,752 261 489 2,218* 2,448 2,517 2,527 2,661 2 , 2 38 243 2,122 137 482 260 593 2,127 2,488 316 452 242 58 66 4 0 0 0 0 I 018 2,714 2,467 2,365 2,550> 4,429 5,503 8 695 20 3 8 0 A, C 1, 230 6,974 3 4," ' 321 2,920 560 2 704 131 569 1, 0 2 9 765 95 319 3,364 306 348 31 2 319 2 43 955 249 156 4,968 5,485 2 , 332 2,879 5,790 ,051 2 0 0 0 2 _ World Catch of Five Major Species of Whales, 1920 to 1971 (Sources: McHugh at 306-07). 738 3,118 2,726 6,742 6 , 204 5 , 338 3,181 6,015 7,238 4,938 5,456 7,245 10,664 9,894 22,514 21,196 CURRENT ESTIMATES OF WHALE POPULATION SIZES IN IQOO's OF WHALES ( % OF INITIAL POPULATION)* So. Hemisphere No. Pacific No Atlantic Bowhead** n o t present 1-2 ? ( 1 0 % ? ) <0.1 (i%?) Right** 3-4 ( < I 0 % > 0.3-0.4 <0.2 ? (unknown) (unknown) Gray** not present 11-12 ( - 1 0 0 % ) Humpback 2-3 ( 3 % I 2 Blue 7-8***(4%) 1.5-2 (30-40%) <1 Fin 80 ( 2 0 % ) 14-19 ( 4 0 % ) >31 Sei 50-55 ( 3 3 1 ) 21-23 >2 Bryde's >10 Minke <90%.') (unknown) i-50%) 20-30 ( - 1 0 0 % . ) 120-200 ( 8 0 % ) unknown Sperm J 128 ( 5 0 % ) 74 ( 4 1 % ) Sperm 9 295 (90^r) 103 ( 8 2 % ) * not present <1.5 (70%?) (10%?) (unknown) (unknown) unknown > 10 ( u n k n o w n ) 38 ( u n k n o w n ) T h e s e figures represent the s t / e s o f the " e x p l o i t a b l e p o p u l a t i o n s " ! . ? . . t h o s e a n i m a l s a b o v e m i n i m u m legal h a r v e s t length. T o e s t i m a t e total stock s,ize, m u l t i p l y e x p l o i t a b l e stock size by 1.5 f o r b a l e e n w h a l e s a n d 2.0 for s p e r m w h a l e s . T h e e s t i m a t e s f o r these species a r e for total stock s u e , not e x p l o i t a b l e stock size. " " T h i s figure i n c l u d e s " a few t h o u s a n d " p y g m y b l u e w h a l e s , a relatively small (70 feet l o n g ) s u b s p e c i e s ( B . musculus brnicauda) f o u n d in the s o u t h e r n I n d i a n O c e a n . ' 5 Appendix F. Current Estimates of Whale Population Sizes (Sources Scarff at 332). 133

![Blue and fin whale populations [MM 2.4.1] Ecologists use the](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008646945_1-b8cb28bdd3491236d14c964cfafa113a-300x300.png)