TAMING THE DRAGON: AN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

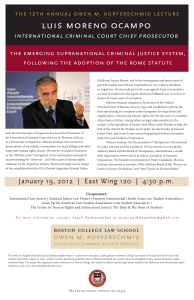

advertisement