Julian Go Boston University

advertisement

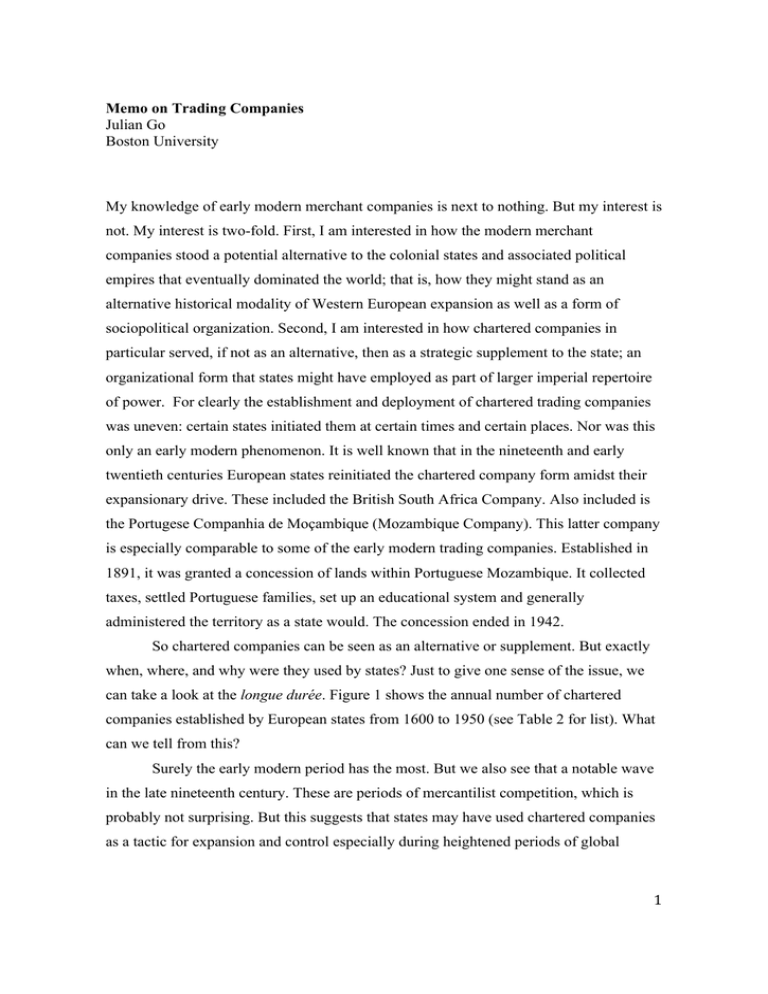

Memo on Trading Companies Julian Go Boston University My knowledge of early modern merchant companies is next to nothing. But my interest is not. My interest is two-fold. First, I am interested in how the modern merchant companies stood a potential alternative to the colonial states and associated political empires that eventually dominated the world; that is, how they might stand as an alternative historical modality of Western European expansion as well as a form of sociopolitical organization. Second, I am interested in how chartered companies in particular served, if not as an alternative, then as a strategic supplement to the state; an organizational form that states might have employed as part of larger imperial repertoire of power. For clearly the establishment and deployment of chartered trading companies was uneven: certain states initiated them at certain times and certain places. Nor was this only an early modern phenomenon. It is well known that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries European states reinitiated the chartered company form amidst their expansionary drive. These included the British South Africa Company. Also included is the Portugese Companhia de Moçambique (Mozambique Company). This latter company is especially comparable to some of the early modern trading companies. Established in 1891, it was granted a concession of lands within Portuguese Mozambique. It collected taxes, settled Portuguese families, set up an educational system and generally administered the territory as a state would. The concession ended in 1942. So chartered companies can be seen as an alternative or supplement. But exactly when, where, and why were they used by states? Just to give one sense of the issue, we can take a look at the longue durée. Figure 1 shows the annual number of chartered companies established by European states from 1600 to 1950 (see Table 2 for list). What can we tell from this? Surely the early modern period has the most. But we also see that a notable wave in the late nineteenth century. These are periods of mercantilist competition, which is probably not surprising. But this suggests that states may have used chartered companies as a tactic for expansion and control especially during heightened periods of global ! 1! economic competition. Unlike the proliferation of transnational companies and export processing zones today, chartered companies are not the mark of liberal global trading regimes. We can explore other possible correlates. As an exploratory device I modeled the annual counts using a negative binomial regression (a common method for count data, negative binomial is a generalization of Poisson-based regression, with the same mean structure, but is preferred to Poisson because it corrects for overdispersion by introducing a stochastic component to the model). The following are the independent variables: a. Total annual number of colonies established by European states (year of establishment). Years entered: 1700-1944. Source: Henige. b. Economic Long Wave (Kondratiev). Dummy variable: 1=expansion, 0 = contraction. Years entered: 1650-1944 c. British relative sea power capabilities. This is a measure of Britain’s relative naval capabilities compared to other powerful states. Developed by Thompson and Modelski, it is captures the relative distribution of naval power. The lower the score, the less is Britain’s global share of naval power; the higher the score, the more is Britain’s share. Years entered: 1607-1944. Source: Modelski and Thompson d. Cycles of Hegemony. Using Wallerstein’s periodization of phases of hegemony, we can arrange world history years into periods of hegemonic stability when one state predominates the world economy (coded “0”) and those of competition when the hegemon declines and global share of economic production is multipolar (coded “1”). Years entered: 1648-1944. Source: Wallerstein. If companies are established amidst periods of heightened economic competition, then we would expect the hegemony variable to be positive and significant. The sea power variable captures superpower competition, not economic competition, and we would expect this not to be significant. The economic long wave variable assesses whether company establishment is driven by economic impetus – that is, a way for states feeling economic stagnation to turn to companies to help: we would expect companies to be established in periods of contraction. Table 1 shows the results. The only significant predictor is number of colonies in the system. If this is telling at all, it suggests that states ! 2! use chartered companies in conjunction with colonization as part of an expansionist strategy – not as an alternative. The findings are surely limited (for instance there is no time trend variable) but nonetheless they might be worth a chat. FIGURE 1. Number of Chartered Companies established per year (1600-1944) 4.5! 4! 3.5! 3! 2.5! 2! 1.5! 1! 0.5! 0! 1600 ! 1630 1660 1690 1720 1750 1780 1810 1840 1870 1900 1930 3! TABLE 1 Negative Binomial Regression Coefficients for Estimating Counts of Company Establishment in the World-System VARIABLE B Number of Colonies Established in the System .312* (.1173) Hegemony -.528 (.3832) Economic Long Wave British Share of World Seapower (Intercept) .538 (.4085) 1.371 (2.362) -3.227* (1.1105) Standard errors in parentheses *sig. at <.05; **sig. at <.01; ***sig. at <.001 (two-tailed) ! 4! Table 2 Chartered Companies, 1600YEAR COMPANY 1600 East India Company 1602 Dutch East India Company 1604 New River Company 1605 Levant Companyb 1606 Virginia Company 1609 French Company 1610 London and Bristol Company 1613 Company of One Hundred Associates 1614 New Netherland Company 1614 Noordsche Compagnie 1614 Nordic Company 1616 Danish East India Companya 1616 Somers Isles Company 1621 Dutch West India Company 1625 Compagnie de Saint-Christophe 1628 Portuguese East India Company 1629 Massachusetts Bay Company 1629 Providence Island Company 1634 Guinea Company of Scotland 1635 Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique 1635 Courteen association 1638 New Sweden Company 1649 Swedish Africa Company 1660 Compagnie de Chine 1664 Compagnie de l'Occident 1664 Compagnie des Indes occidentales 1664 Compagnie des Indes Orientales 1664–1674 Royal West Indian Company 1670 Hudson's Bay Company 1671 Danish West India Company 1672 Royal African Company 1682 Brandenburg African Company 1693 Greenland Company 1698 Company of Scotland 1711 South Sea Company 1717 Compagnie du Mississippi 1717 Ostend Companya 1720 Society of Berbice ! COUNTRY England Belgium/Netherlands/Luxembourg England England England England England France Belgium/Netherlands/Luxembourg Belgium/Netherlands/Luxembourg Belgium/Netherlands/Luxembourg Scandinavia England Belgium/Netherlands/Luxembourg France Portugal England England Scotland France England Scandinavia Scandinavia France France France France England England Scandinavia England Germany England Scotland England France Belgium/Netherlands/Luxembourg Belgium/Netherlands/Luxembourg 5! 1721 Bergen Greenland Company 1731 Swedish East India Company 1738 Swedish Levant Companye 1749 General Trade Company 1752 African Company of Merchants 1752 Emden Company 1774 Royal Greenland Trading Department 1786 Swedish West India Companyd 1792 Sierra Leone Company 1799 Russian American Company 1824 Van Diemen's Land Company 1835 South Australian Company 1839 New Zealand Company 1847 Eastern Archipelago Company 1881 British North Borneo Company 1882 German West African Company 1884 German East Africa Company 1884 German New Guinea Company 1886 Royal Niger Company 1888 Companhia de Moçambique 1889 British South Africa Company 1891 Astrolabe Company 1891 Companhia do Niassa ! Scandinavia Scandinavia Scandinavia Scandinavia England Germany Scandinavia Scandinavia England Russia England England England England England Germany Germany Germany England Portugal England Germany Portugal 6!