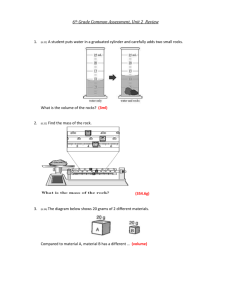

for the January 30, 1969 in Agricultural Economics presented on

advertisement