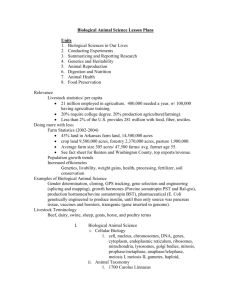

Robert Lee Oehrtman for the Date thesis is presented Agricultural Economics

advertisement