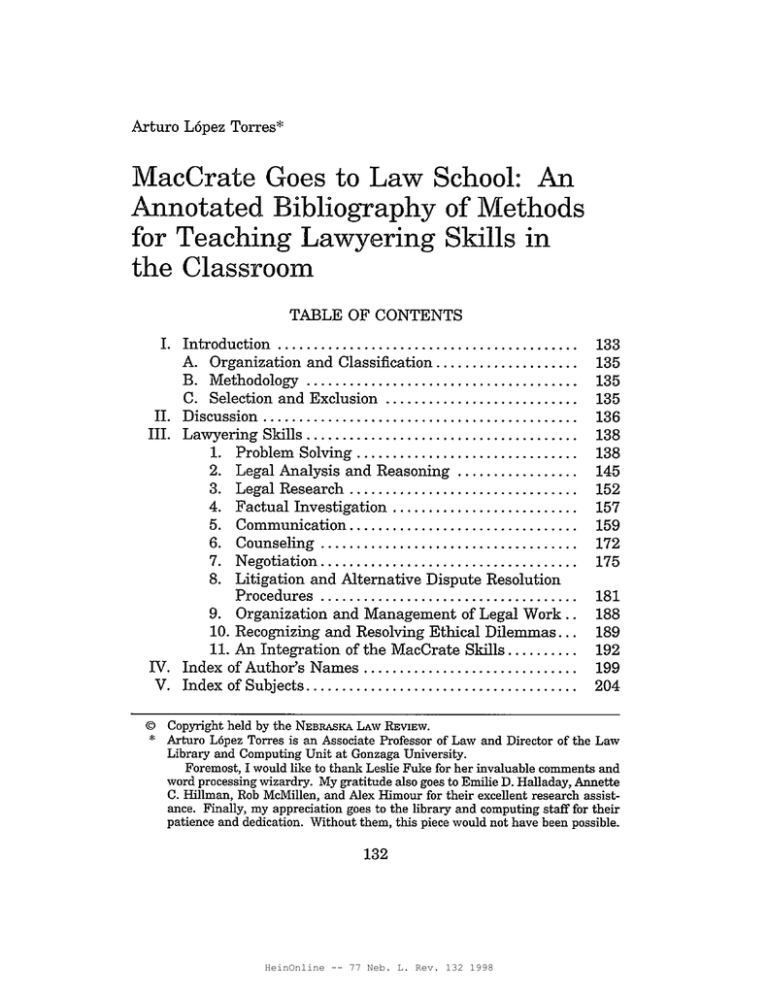

MacCrate Goes to Law School: Annotated Bibliography of Methods the Classroom

advertisement