Athenian Homicide Law and the Model Penal Code ngeles ( )

advertisement

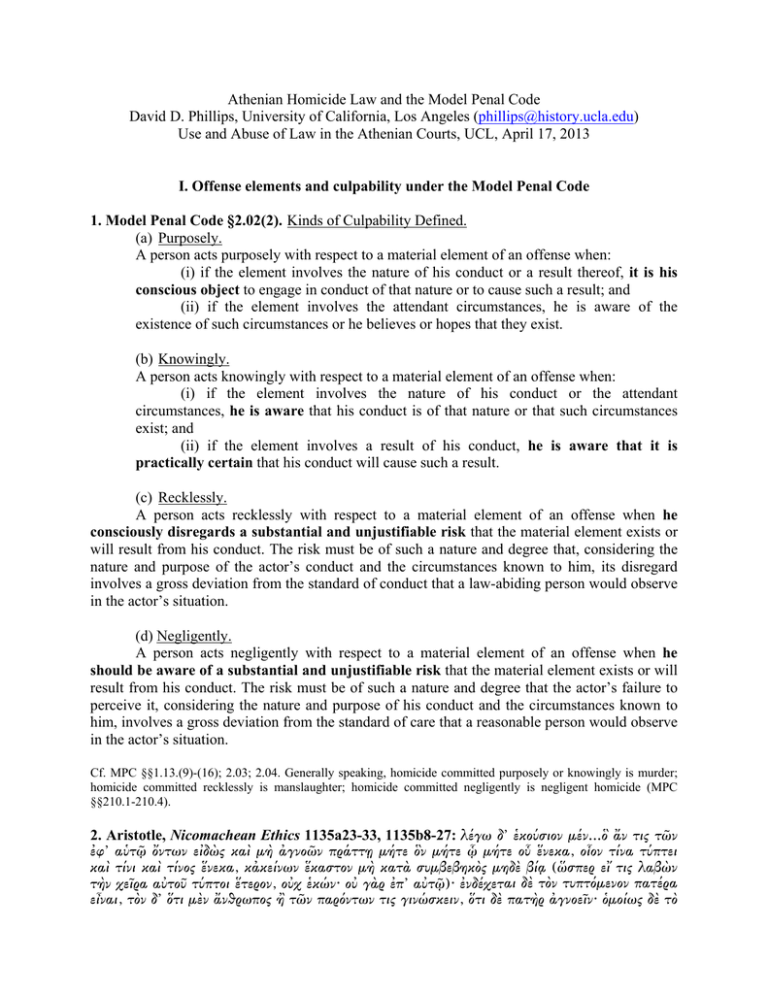

Athenian Homicide Law and the Model Penal Code David D. Phillips, University of California, Los Angeles (phillips@history.ucla.edu) Use and Abuse of Law in the Athenian Courts, UCL, April 17, 2013 I. Offense elements and culpability under the Model Penal Code 1. Model Penal Code §2.02(2). Kinds of Culpability Defined. (a) Purposely. A person acts purposely with respect to a material element of an offense when: (i) if the element involves the nature of his conduct or a result thereof, it is his conscious object to engage in conduct of that nature or to cause such a result; and (ii) if the element involves the attendant circumstances, he is aware of the existence of such circumstances or he believes or hopes that they exist. (b) Knowingly. A person acts knowingly with respect to a material element of an offense when: (i) if the element involves the nature of his conduct or the attendant circumstances, he is aware that his conduct is of that nature or that such circumstances exist; and (ii) if the element involves a result of his conduct, he is aware that it is practically certain that his conduct will cause such a result. (c) Recklessly. A person acts recklessly with respect to a material element of an offense when he consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element exists or will result from his conduct. The risk must be of such a nature and degree that, considering the nature and purpose of the actor’s conduct and the circumstances known to him, its disregard involves a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a law-abiding person would observe in the actor’s situation. (d) Negligently. A person acts negligently with respect to a material element of an offense when he should be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element exists or will result from his conduct. The risk must be of such a nature and degree that the actor’s failure to perceive it, considering the nature and purpose of his conduct and the circumstances known to him, involves a gross deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the actor’s situation. Cf. MPC §§1.13.(9)-(16); 2.03; 2.04. Generally speaking, homicide committed purposely or knowingly is murder; homicide committed recklessly is manslaughter; homicide committed negligently is negligent homicide (MPC §§210.1-210.4). 2. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1135a23-33, 1135b8-27: λέγω δ’ ἑκούσιον μέν...ὃ ἄν τις τῶν ἐφ’ αὑτῷ ὄντων εἰδὼς καὶ μὴ ἀγνοῶν πράττῃ μήτε ὃν μήτε ᾧ μήτε οὗ ἕνεκα, οἷον τίνα τύπτει καὶ τίνι καὶ τίνος ἕνεκα, κἀκείνων ἕκαστον μὴ κατὰ συμβεβηκὸς μηδὲ βίᾳ (ὥσπερ εἴ τις λαβὼν τὴν χεῖρα αὐτοῦ τύπτοι ἕτερον, οὐχ ἑκών· οὐ γὰρ ἐπ’ αὐτῷ)· ἐνδέχεται δὲ τὸν τυπτόμενον πατέρα εἶναι, τὸν δ’ ὅτι μὲν ἄνθρωπος ἢ τῶν παρόντων τις γινώσκειν, ὅτι δὲ πατὴρ ἀγνοεῖν· ὁμοίως δὲ τὸ τοιοῦτον διωρίσθω καὶ ἐπὶ τοῦ οὗ ἕνεκα, καὶ περὶ τὴν πρᾶξιν ὅλην. τὸ δὴ ἀγνοούμενον, ἢ μὴ ἀγνοούμενον μὲν μὴ ἐπ’ αὐτῷ δ’ ὄν, ἢ βίᾳ, ἀκούσιον. ... τῶν δὲ ἑκουσίων τὰ μὲν προελόμενοι πράττομεν τὰ δ’ οὐ προελόμενοι, προελόμενοι μὲν ὅσα προβουλευσάμενοι, ἀπροαίρετα δὲ ὅσ’ ἀπροβούλευτα. τριῶν δὴ οὐσῶν βλαβῶν τῶν ἐν ταῖς κοινωνίαις, τὰ μὲν μετ’ ἀγνοίας ἁμαρτήματά ἐστιν, ὅταν μήτε ὃν μήτε ὃ μήτε ᾧ μήτε οὗ ἕνεκα ὑπέλαβε πράξῃ· ἢ γὰρ οὐ βάλλειν ἢ οὐ τούτῳ ἢ οὐ τοῦτον ἢ οὐ τούτου ἕνεκα ᾠήθη, ἀλλὰ συνέβη οὐχ οὗ ἕνεκα ᾠήθη, οἷον οὐχ ἵνα τρώσῃ ἀλλ’ ἵνα κεντήσῃ, ἢ οὐχ ὅν, ἢ οὐχ ᾧ. ὅταν μὲν οὖν παραλόγως ἡ βλάβη γένηται, ἀτύχημα· ὅταν δὲ μὴ παραλόγως, ἄνευ δὲ κακίας, ἁμάρτημα (ἁμαρτάνει μὲν γὰρ ὅταν ἡ ἀρχὴ ἐν αὐτῷ ᾖ τῆς αἰτίας, ἀτυχεῖ δ’ ὅταν ἔξωθεν)· ὅταν δὲ εἰδὼς μὲν μὴ προβουλεύσας δέ, ἀδίκημα, οἷον ὅσα τε διὰ θυμὸν καὶ ἄλλα πάθη, ὅσα ἀναγκαῖα ἢ φυσικὰ συμβαίνει τοῖς ἀνθρώποις...ὅταν δ’ ἐκ προαιρέσεως, ἄδικος καὶ μοχθηρός. διὸ καλῶς τὰ ἐκ θυμοῦ οὐκ ἐκ προνοίας κρίνεται· οὐ γὰρ ἄρχει ὁ θυμῷ ποιῶν, ἀλλ’ ὁ ὁργίσας. I call intentional...that which a person, among things in his power, does with knowledge and without ignorance of the person to whom he does it, the instrument with which he does it, and the end to which he does it – for example, whom he is hitting, with what, and to what end – each of the aforementioned occurring neither by chance nor by compulsion (as, for example, if someone else took his hand and struck a third person, he is not intentional, since it is not within his power). The person struck may be his father, and he may know that it is a person or one of those present but not know that it is his father; a similar distinction must be made in the case of the end and concerning the act in its entirety. That which is unknown, or not unknown but not in one’s power, or done by compulsion, is unintentional. ... Among intentional acts, we do some by deliberate choice and others not by deliberate choice. We do by deliberate choice what we have deliberated upon; all acts not deliberated upon are not by deliberate choice. Of the three types of harm in interactions, those that occur in ignorance are errors when the person acted upon, the act, the instrument, or the end is not what the actor supposed: he thought that he was not throwing to strike, or not with this instrument, or not this person, or not to this end, but the result was not the end he had in mind – for example, he threw not to wound but to prick – or that the person he struck or the instrument with which he struck was not what he had in mind. Now, when harm occurs contrary to reasonable expectation, it is an accident; but when it occurs not contrary to reasonable expectation but without vice, it is an error (for a person commits an error when the origin of the offense is in him, but suffers an accident when the origin is outside him). When he acts knowingly but not deliberately, it is an unjust act, such as all acts done on account of anger and other emotions that are necessary or natural for people. ... But when he acts by deliberate choice, he is an unjust and bad person. Therefore, acts resulting from anger are rightly judged not to be the result of forethought (ek pronoias), since the initiator is not the one acting in anger but the one who caused the anger. Cf. EN 1109b30-1114b25; Rhet. 1368b9-12, 1373b33-1374a17, 1374b4-10, 1375a7. Plato’s homicide law (Laws 865a-874d) categorizes killings as follows: (1) 865a-866d: (violent and) unintentional killing (τὰ βίαια καὶ ἀκούσια, 865a2-3); (2) 866d-869e: killing in anger (θυμῷ, 866d5), itself divided (867a-b) into (a) killing by those who act on the spur of the moment and without a preconceived intent to kill (ὅσοι ἂν ἐξαίφνης μὲν καὶ ἀπροβούλευτως τοῦ ἀποκτεῖναι πληγαῖς ἤ τινι τοιούτῳ διαφθείρωσί τινα παραχρῆμα τῆς ὀργῆς γενομένης) (and who immediately regret the act), which is an εἰκών of unintentional killing, and (b) killing by those who delay vengeance for a slight in word or deed and after some time kill with preconceived intent (ὕστερον ἀποκτείνωσί τινα βουληθέντες κτεῖναι) (and who do not regret the act), which is an εἰκών of intentional killing; (3) 869e-873d: intentional (and fully unjust) killing (τὰ ἑκούσια καὶ κατ’ ἀδικίαν πᾶσαν γιγνόμενα), which (unlike in Athenian law) is ἐκ προνοίας in the full sense of the phrase (cf. 871a1ff.: νόμος ὅδε εἰρῆσθω τῇ γραφῇ· Ὅς ἂν ἐκ προνοίας τε καὶ ἀδίκως ὁντιναοῦν τῶν ἐμφυλίων αὐτόχειρ κτείνῃ κτλ); (4) 873d-874a: killing by non-humans; (5) 874a-b: killing by 2 an unidentified killer; (6) 874b-d: lawful (justifiable) killing (ὧν δὲ ἐφ’ οἷς τε ὀρθῶς ἂν καθαρὸς εἴη [scil. ὁ ἀποκτείνας]). The cases in category (6) (the killing of a nocturnal thief within the house; of a clothes-snatcher in self-defense (λωποδύτην ἀμυνόμενος); of the rapist of a free woman or child by the victim or the victim’s father, brother, son, or husband; or in defense of one’s father, mother, child, sibling, or spouse against lethal force, provided that the defended person be innocent of wrongdoing) and the special cases that open category (1) (public athletic competition, warfare or training for war, doctors) are circumstantial; category (6) contains justifiable homicides and the beginning of category (1) contains excusable homicides. Category (6) with its justifying circumstances is so important to Plato(’s Athenian Stranger) that he sets it off as Section 2 of the homicide law (with all preceding – categories (1) through (5) – as Section 1: οὗτος δὴ νόμος εἷς ἡμῖν ἔστω κύριος περὶ φόνου κείμενος, 874b4-5). II. Conduct, circumstance, result, and volition in Athenian homicide law 3. Draco’s law a. IG I3 104.11-13: [δ]ικάζεν δὲ τὸς βασιλέας αἴτιο[ν] φόνο ἒ [τὸν αὐτόχερ κτέναντ’] ἒ [β]ολεύσαντα... The basileis shall judge him guilty of homicide whether he killed with his own hand or conspired to kill... b. IG I3 104.26-31 (= Dem. 23.37 (lex) + Dem. 23.28 (lex)): ἐὰν δ]έ [τ]ις τὸ[ν ἀν]δρ[οφόνον κτένει ἒ αἴτιος ι φόνο, ἀπεχόμενον ἀγορᾶ]ς ἐφορί[α]ς κ[α]ὶ [ἄθλον καὶ ἱερν Ἀμφικτυονικν, hόσπερ τὸν Ἀθεν]αῖον κ[τένα]ν[τα, ἐν τοῖς αὐτοῖς ἐνέχεσθαι· διαγιγνόσκεν δὲ τὸς] ἐ[φ]έτα[ς. ... τὸς δ’ ἀνδροφόνος ἐξναι ἀποκτένεν ἐν] τι ἑμεδ[απι καὶ ἀπάγεν... And if a person kills the killer or is responsible for his killing, when the killer has stayed away from the border-market, games, and Amphictyonic rites, he shall be bound by the same terms as the killer of an Athenian; the ephetai shall decide the case. ... And it shall be permitted to kill or arrest killers in our land... c. IG I3 104.37-38 (= Dem. 23.60 (lex)): κα[ὶ ἐὰν φέροντα ἒ ἄγοντα βίαι ἀδίκος εὐθὺς] ἀμυνόμενος κτέ[ν]ει, ν[εποινὲ τεθνάναι... And if in immediate self-defense he kills someone carrying or leading away [his property] forcibly and without justification, the death shall be uncompensated. d. IG I3 104.33-36: ...39... ἄρχον]τα χερν ἀ[δίκον ...30... χερ]ν ἀδίκον κτέ[νει ...7... ]σ [...19... διαγιγνόσκ]εν δὲ τὸς ἐ[φέτ]ας... ...starting a fight without justification...a fight without justification, he kills...the ephetai shall decide the case... e. Dem. 23.44 (lex): ἐάν τίς τινα τῶν ἀνδροφόνων τῶν ἐξεληλυθότων, ὧν τὰ χρήματα ἐπίτιμα, πέρα ὅρου ἐλαύνῃ ἢ φέρῃ ἢ ἄγῃ, τὰ ἴσα ὀφείλειν ὅσα περ ἂν ἐν τῇ ἡμεδαπῇ δράσῃ. 3 If, beyond the border, a person drives, carries, or leads [the person and/or property of] one of the killers who have left the country and whose property is unconfiscated, he shall owe the same amount as if he committed the act in our land. Interpretation as providing against the forcible repatriation of the killer: §49. f. Dem. 23.51 (lex): φόνου δὲ δίκας μὴ εἶναι μηδαμοῦ κατὰ τῶν τοὺς φεύγοντας ἐνδεικνύντων, ἐάν τις κατίῃ ὅποι μὴ ἔξεστιν. There shall be no dikai phonou anywhere against those who denounce exiles, if one of them returns where he is not allowed. g. Dem. 23.53 (lex): ἐάν τις ἀποκτείνῃ ἐν ἄθλοις ἄκων, ἢ ἐν ὁδῷ καθελὼν ἢ ἐν πολέμῳ ἀγνοήσας, ἢ ἐπὶ δάμαρτι ἢ ἐπὶ μητρὶ ἢ ἐπὶ ἀδελφῇ ἢ ἐπὶ θυγατρί, ἢ ἐπὶ παλλακῇ ἣν ἂν ἐπὶ ἐλευθέροις παισὶν ἔχῃ, τούτων ἕνεκα μὴ φεύγειν κτείναντα. If a person kills unintentionally in the games, or having come upon a highwayman on the road, or in war without recognizing his victim, or [finding his victim] upon his consort, mother, sister, daughter, or concubine whom he keeps for the procreation of free children, for these acts he shall not stand trial as a killer. Demosthenes’ interpretation (§54): the lawgiver “looked not to what happened (τὸ συμβάν: bare conduct and/or result without regard for the actor’s volition, as demonstrated by what follows) but to the purpose of the actor (τὴν τοῦ δεδρακότος διάνοιαν). And what is that? To defeat a living opponent, not to kill (ζῶντα νικῆσαι καὶ οὐκ ἀποκτεῖναι).” III. Conduct, circumstance, result, and volition in forensic argument (and beyond) 4. Lysias 1.37: κατηγοροῦσι γάρ μου ὡς ἐγὼ τὴν θεράπαιναν ἐν ἐκείνῃ τῇ ἡμέρᾳ μετελθεῖν ἐκέλευσα τὸν νεανίσκον. ἐγὼ δέ, ὦ ἄνδρες, δίκαιον μὲν ἂν ποιεῖν ἡγούμην ᾡτινιοῦν τρόπῳ τὸν τὴν γυναῖκα τὴν ἐμὴν διαφθείραντα λαμβάνων. They accuse me of ordering my slave on that day to fetch the young man. But for my part, gentlemen, I would think I was acting justly in catching by any means whatsoever the man who had corrupted my wife. Prosecution contends that Eratosthenes was dragged in off the road and fled to the altar inside: §27. Citation of ἐπὶ δάμαρτι clause (3g): §30. 5. Demosthenes 21.71, 73-75: ἴσασιν Εὐαίωνα πολλοὶ τὸν Λεωδάμαντος ἀδελφόν, ἀποκτείναντα Βοιωτὸν ἐν δείπνῳ καὶ συνόδῳ οἰκείων διὰ πληγὴν μίαν. ... ὁ μέν γε ὑπὸ γνωρίμου, καὶ τούτου μεθύοντος, ἐναντίον ἓξ ἢ ἐπτὰ ἀνθρώπων ἐπλήγη... τῷ δ’ Εὐαίωνι καὶ πᾶσιν, εἴ τις αὑτῷ βεβοήθηκεν ἀτιμαζόμενος, πολλὴν συγγνώμην ἔχω. δοκοῦσι δέ μοι καὶ τῶν δικασάντων τότε πολλοί· ἀκούω γὰρ αὐτὸν ἔγωγε μιᾷ μόνον ἁλῶναι ψήφῳ, καὶ ταῦτα οὔτε κλαύσαντα οὔτε δεηθέντα τῶν δικαστῶν οὐδενός, οὔτε φιλάνθρωπον οὔτε μικρὸν οὔτε μέγα οὐδ’ ὁτιοῦν πρὸς τοὺς δικαστὰς ποιήσαντα. θῶμεν τοίνυν οὑτωσί, τοὺς μὲν καταγνόντας αὐτοῦ μὴ ὅτι ἠμύνατο, διὰ τοῦτο καταψηφίσασθαι, ἀλλ’ ὅτι τοῦτον τὸν τρόπον ὥστε καὶ ἀποκτεῖναι, τοὺς δ’ ἀπογνόντας καὶ ταύτην τὴν ὑπερβολὴν τῆς τιμωρίας τῷ γε τὸ σῶμα ὑβρισμένῳ δεδωκέναι. 4 Many people know that Euaeon, the brother of Leodamas, killed Boeotus at a dinner gathering of friends on account of a single blow. ... He was struck by an acquaintance, who was drunk, in the presence of six or seven people. ... I have great sympathy for Euaeon and anyone who has come to his own aid against dishonor. And so, it seems to me, did many of the jurors on that occasion; for I hear that he was convicted by a margin of only one vote, and that when he had not cried or begged any of the jurors, and had made absolutely no gesture of generosity, great or small, toward the jurors. Let us, then, suppose that the jurors who voted to convict him did so not because he had defended himself but because he had done so in such a manner as to kill, while those who voted to acquit allowed even this excess of vengeance to a man whose person had been the victim of hubris. 6. Isaeus 9.17, 19: Εὐθυκράτει γάρ, ὦ ἄνδρες, τῷ πατρὶ τῷ Ἀστυφίλου αἴτιος γενέσθαι λέγεται τοῦ θανάτου Θούδιππος ὁ Κλέωνος τουτουὶ πατήρ, αἰκισάμενος ἐκεῖνον διαφορᾶς τινος αὐτοῖς γενομένης ἐν τῇ νεμήσει τοῦ χωρίου, καὶ οὕτως αὐτὸν διατεθῆναι ὥστε ἐκ τῶν πληγῶν ἀσθενήσαντα οὐ πολλαῖς ἡμέραις ὕστερον ἀποθανεῖν. ... ὅτε ἀπέθνῃσκεν Εὐθυκράτης...ἐπέσκηψε τοῖς οἰκείοις μηδένα ποτὲ ἐᾶσαι ἐλθεῖν τῶν Θουδίππου ἐπὶ τὸ μνῆμα τὸ ἑαυτοῦ... You see, gentlemen, Thudippus, the father of my adversary Cleon here, is said to have been responsible for the death of Euthycrates, the father of Astyphilus: when a dispute arose between them during the division of their land, Thudippus assaulted Euthycrates, and Euthycrates was in such poor condition that, as a result of the blows, he fell ill and died a few days later. ... when Euthycrates lay dying, he enjoined his family never to allow any of Thudippus’ family to visit his tomb... 7. Antiphon 4 (Third Tetralogy) a. Ant. 4 β 1-4: ἄρχων γὰρ χειρῶν ἀδίκων...οὐχ αὑτῷ μόνον τῆς συμφορᾶς ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐμοὶ τοῦ ἐγκλήματος αἴτιος γέγονεν. ... τὸν γὰρ ἄρξαντα τῆς πληγῆς, εἰ μὲν σιδήρῳ ἢ λίθῳ ἢ ξύλῳ ἠμυνάμην αὐτόν, ἠδίκουν μὲν οὐδ’ οὕτως -- οὐ γὰρ ταὐτὰ ἀλλὰ μείζονα καὶ πλείονα δίκαιοι οἱ ἄρχοντες ἀντιπάσχειν εἰσί --· ταῖς δὲ χερσὶ τυπτόμενος ὑπ’ αὐτοῦ, ταῖς χερσὶν ἅπερ ἔπασχον ἀντιδρῶν, πότερα ἠδίκουν; Εἶεν· ἐρεῖ δὲ ‘ἀλλ’ ὁ νόμος εἴργων μήτε δικαίως μήτε ἀδίκως ἀποκτείνειν ἔνοχον τοῦ φόνου τοῖς ἐπιτιμίοις ἀποφαίνει σε ὄντα· ὁ γὰρ ἀνὴρ τέθνηκεν.’ ἐγὼ δὲ δεύτερον καὶ τρίτον οὐκ ἀποκτεῖναί φημι. εἰ μὲν γὰρ ὑπὸ τῶν πληγῶν ὁ ἀνὴρ παραχρῆμα ἀπέθανεν, ὑπ’ ἐμοῦ μὲν δικαίως δ’ ἂν ἐτεθνήκει -- οὐ γὰρ ταὐτὰ ἀλλὰ μείζονα καὶ πλείονα οἱ ἄρξαντες δίκαιοι ἀντιπάσχειν εἰσί --· νῦν δὲ πολλαῖς ἡμέραις ὕστερον μοχθηρῷ ἰατρῷ ἐπιτρεφθεὶς διὰ τὴν τοῦ ἰατροῦ μοχθηρίαν καὶ οὐ διὰ τὰς πληγὰς ἀπέθανε. By starting the fight without justification...he became responsible not only for his own misfortune but also for the charge against me. ... He struck the first blow; if I had defended myself with a blade, rock, or club, even then I would be guilty of no wrong, since aggressors deserve to suffer not the same as they inflict but worse and more. But in fact, he was striking me with his hands, and I retaliated with my hands for the beating I was taking; did I do wrong? Well, [the prosecutor] will say, “But the law prohibiting both just and unjust killing declares you liable to the penalties for homicide, since the man is dead.” But I say, for the 5 second and third time, that I did not kill. If the man had died immediately from the blows, he would have died at my hands, and justly, since aggressors deserve to suffer not the same as they inflict but worse and more. In fact, though, many days later, having been entrusted to an incompetent doctor, he died on account of the doctor’s incompetence, not on account of the blows. For the homicide law of the Tetralogies cf. Ant. 3 β 5, 3 γ 7; 4 α 7 (penalty of death for intentional homicide). b. Ant. 4 γ 4: ὁ μὲν γὰρ ἐξ ὧν ἔδρασεν ἐκεῖνος διαφθαρείς, οὐ τῇ ἑαυτοῦ ἁμαρτίᾳ ἀλλὰ τῇ τοῦ πατάξαντος χρησάμενος ἀπέθανεν· ὁ δὲ μεί̅ζω̅ ὧ̅ν ἤ̅θε̆λε̆ πρά̅ξα̅ς, τῇ ἑαυτοῦ ἀτυχίᾳ ὃν οὐκ ἤθελεν ἀπέκτεινεν. [The victim] was killed as a result of what that man did and died not by his own error but by that of the man who hit him; [the defendant] did more than he wanted and by his own misfortune killed a man whom he did not want to kill. 8. Plato, Euthyphro 4c3-e3: ὁ οὖν πατὴρ συνδήσας τοὺς πόδας καὶ τὰς χεῖρας αὐτοῦ, καταβαλὼν εἰς τάφρον τινά, πέμπει δεῦρο ἄνδρα πευσόμενον τοῦ ἐξηγητοῦ ὅτι χρείη ποιεῖν. ἐν δὲ τούτῳ τῷ χρόνῳ τοῦ δεδεμένου ὠλιγώρει τε καὶ ἠμέλει ὡς ἀνδροφόνου καὶ οὐδὲν ὂν πρᾶγμα εἰ καὶ ἀποθάνοι, ὅπερ οὖν καὶ ἔπαθεν· ὑπὸ γὰρ λιμοῦ καὶ ῥίγους καὶ τῶν δεσμῶν ἀποθνῄσκει πρὶν τὸν ἄγγελον παρὰ τοῦ ἐξηγητοῦ ἀφικέσθαι. ταῦτα δὴ οὖν καὶ ἀγανακτεῖ ὅ τε πατὴρ καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι οἰκεῖοι, ὅτι ἐγὼ ὑπὲρ τοῦ ἀνδροφόνου τῷ πατρὶ φόνου ἐπεξέρχομαι οὔτε ἀποκτείναντι, ὥς φασιν ἐκεῖνοι, οὔτ’ εἰ ὅτι μάλιστα ἀπέκτεινεν, ἀνδροφόνου γε ὄντος τοῦ ἀποθανόντος, οὐ δεῖν φροντίζειν ὑπὲρ τοῦ τοιούτου -- ἀνόσιον γὰρ εἶναι τὸ ὑὸν πατρὶ φόνου ἐπεξιέναι... So my father bound his feet and hands, threw him into a ditch, and sent a man here to find out from the Interpreter what he should do. In the meantime, he ignored and neglected the prisoner, since he was a killer and it was no matter even if he died – which is exactly what happened: he died of hunger, cold, and his bonds before the messenger returned from the Interpreter. So my father and the rest of my family are angry because I am prosecuting my father for homicide on behalf of the killer, when my father did not kill him (as they say), and even if he absolutely did kill him, as the dead man was a killer, one should not be concerned about a person of that sort, for it is impious for a son to prosecute his father for homicide... 9. Antiphon 3 (Second Tetralogy) a. Ant. 3 β 3: τὸ γὰρ μειράκιον οὐχ ὕβρει οὐδὲ ἀκολασίᾳ, ἀλλὰ μελετῶν μετὰ τῶν ἡλίκων ἀκοντίζειν ἐν τῷ γυμνασίῳ, ἔβαλε μέν, οὐκ ἀπέκτεινε δὲ οὐδένα κατά γε τὴν ἀλήθειαν ὧν ἔπραξεν... The youth, not out of hubris or lack of self-control, but practicing javelin-throwing with his agemates in the gymnasium, threw, but he did not kill anyone, according to the truth of what he did... b. Ant. 3 δ 5: θέλω δὲ μὴ πρότερον ἐπ’ ἄλλον λόγον ὁρμῆσαι ἢ τὸ ἔργον ἔτι φανερώτερον καταστῆσαι ὁποτέρου αὐτῶν ἐστί. τὸ μὲν μειράκιον οὐδενὸς μᾶλλον τῶν συμμελετώντων ἐστὶ τοῦ σκοποῦ ἁμαρτόν, οὐδὲ τῶν ἐπικαλουμένων τι διὰ τὴν αὑτοῦ ἁμαρτίαν δέδρακεν· ὁ δὲ παῖς οὐ ταὐτὰ τοῖς συνθεωμένοις δρῶν, ἀλλ’ εἰς τὴν ὁδὸν τοῦ ἀκοντίου ὑπελθών, 6 σαφῶς δηλοῦται παρὰ τὴν αὑτοῦ ἁμαρτίαν περισσοτέροις ἀτυχήμασι τῶν ἀτρεμιζόντων περιπεσών. I do not want to advance to another argument before establishing even more clearly to which of them the act belongs. The youth did not miss the target any more than any of the others who were practicing with him, and he did not do any of the things he is charged with through his own error. The boy, though, did not do the same as his fellow spectators but ran into the path of the javelin, and so is clearly shown to have incurred by his own error greater misfortunes than those who stood still. Cf. 3 β 8: τῆς δὲ ἁμαρτίας εἰς τοῦτον ἡκούσης, τό <τ’> ἔργον οὐχ ἡμέτερον ἀλλὰ τοῦ ἐξαμαρτόντος ἐστι “Since the error belongs to [the victim], the act is not ours but belongs to the one who committed the error.” c. Ant. 3 γ 6: ὁ μὲν γὰρ ἐν τούτῳ τῷ καιρῷ καλούμενος ὑπὸ τοῦ παιδοτρίβου, ὡς ὑποδέχοιτο τοῖς ἀκοντίζουσι τὰ ἀκόντια ἀναιρεῖσθαι, διὰ τὴν τοῦ βαλόντος ἀκολασίαν πολεμίῳ τῷ τούτου βέλει περιπεσών, οὐδὲν οὐδ’ εἰς ἕν’ ἁμαρτών, ἀθλίως ἀπέθανε· ὁ δὲ περὶ τὸν τῆς ἀναιρέσεως καιρὸν πλημμελήσας...ἑκὼν μὲν οὐκ ἀπέκτεινε, μᾶλλον δὲ ἑκὼν ἢ οὔτε ἔβαλεν οὔτε ἀπέκτεινεν. [The victim] was called at that moment by the trainer, who was in charge of recovering the javelins for the throwers. On account of the thrower’s lack of self-control, he met with his hostile missile; having committed no error against anyone, he died wretchedly. The thrower, however, made a mistake regarding the moment of recovery...; he did not kill intentionally, but it is better to say that he killed intentionally than that he neither threw nor killed. d. Ant. 3 β 4-5: τοῦ δὲ παιδὸς ὑπὸ τὴν τοῦ ἀκοντίου φορὰν ὑποδραμόντος καὶ τὸ σῶμα προστήσαντος, ... ὁ δὲ ὑπὸ τὸ ἀκόντιον ὑπελθὼν ἐβλήθη, καὶ τὴν αἰτίαν οὐχ ἡμέτερον οὖσαν προσέβαλεν ἡμῖν. διὰ δὲ τὴν ὑποδρομὴν βληθέντος τοῦ παιδός, τὸ μὲν μειράκιον οὐ δικαίως ἐπικαλεῖται, οὐδένα γὰρ ἔβαλε τῶν ἀπὸ τοῦ σκοποῦ ἀφεστώτων· ὁ δὲ παῖς εἴπερ ἑστὼς φανερὸς ὑμῖν ἐστὶ μὴ βληθείς, ἑκουσίως <δ’> ὑπὸ τὴν φορὰν τοῦ ἀκοντίου ὑπελθών, ἔτι σαφεστέρως δηλοῦται διὰ τὴν αὑτοῦ ἁμαρτίαν ἀποθανών... Because the boy ran under the path of the javelin and put his body in front of it, ... he was hit because he ran under the javelin; and he has hit us with the responsibility, which is not ours. Since the boy was hit on account of his running under, the youth is not justly charged, since he hit none of those who were standing away from the target. As for the boy, if it is clear to you that he was hit not while standing still but having intentionally gone under the path of the javelin, then he is shown even more clearly to have died through his own error... Ant. 3 δ 7: ἔστι δὲ οὐδὲ τὸ ἁμάρτημα τοῦ παιδὸς μόνον, ἀλλὰ καὶ ἡ ἀφυλαξία. ὁ μὲν γὰρ οὐδένα ὁρῶν διατρέχοντα πῶς ἂν ἐφυλάξατο μηδένα βαλεῖν; ὁ δ’ ἰδὼν τοὺς ἀκοντίζοντας εὐπετῶς ἂν ἐφυλάξατο μὴ βληθῆναι· ἐξῆν γὰρ αὐτῷ ἀτρέμα ἑστάναι. And it is not just the error that belongs to the boy, but the lack of care as well. How could the thrower, seeing no one running across, have taken care not to hit anyone? But 7 the boy, seeing the people throwing javelins, could easily have taken care not to get hit: he could have stood still. e. Ant. 3 γ 10-11: ὡς δὲ οὐδὲ τῆς ἁμαρτίας οὐδὲ τοῦ ἀκουσίως ἀποκτεῖναι...ἀπολύεται, ἀλλὰ κοινὰ ἀμφότερα ταῦτα ἀμφοῖν αὐτοῖν ἐστι, δηλώσω. εἴπερ ὁ παῖς διὰ τὸ ὑπὸ τὴν φορὰν τοῦ ἀκοντίου ὑπελθεῖν καὶ μὴ ἀτρέμας ἑστάναι φονεὺς αὐτὸς αὑτοῦ δίκαιος εἶναί ἐστιν, οὐδὲ τὸ μειράκιον καθαρὸν τῆς αἰτίας ἐστίν, ἀλλ’ εἴπερ τούτου μὴ ἀκοντίζοντος ἀλλ’ ἀτρέμα ἑστῶτος ἀπέθανεν ὁ παῖς. ἐξ ἀμφοῖν δὲ τοῦ φόνου γενομένου, ... ὁ δὲ συλλήπτωρ καὶ κοινωνὸς...τῆς ἁμαρτίας γενόμενος πῶς δίκαιος ἀζήμιος ἀποφυγεῖν ἐστιν; ἐκ δὲ τῆς αὐτῶν τῶν ἀπολογουμένων ἀπολογίας μετόχου τοῦ μειρακίου τοῦ φόνου ὄντος, οὐκ ἂν δικαίως οὐδὲ ὁσίως ἀπολύοιτε αὐτόν. I shall demonstrate that he is absolved neither of the error nor of the unintentional killing, but that both these things belong jointly to the two of them. If the boy, because he went under the path of the javelin and did not stand still, is rightly considered his own killer, then the youth is not clear of responsibility either; that would be the case only if he was not throwing but standing still when the boy died. Since the homicide occurred as a result of both of them, ... how does the one who was an accomplice and partner in the error deserve to escape unpunished? Since from the argument of the defense itself the youth is a participant in the homicide, you could not justly or piously acquit him. f. Ant. 3 δ 6, 10 (cf. 9b, 9d): ὡς δ’ οὐδενὸς μᾶλλον τῶν συνακοντιζόντων μέτοχός ἐστι τοῦ φόνου, διδάξω. εἰ γὰρ διὰ τὸ τοῦτον ἀκοντίζειν ὁ παῖς ἀπέθανε, πάντες ἂν οἱ συμμελετῶντες συμπράκτορες εἴησαν τῆς αἰτίας· οὗτοι γὰρ οὐ διὰ τὸ μὴ ἀκοντίζειν οὐκ ἔβαλον αὐτόν, ἀλλὰ διὰ τὸ μηδενὶ ὑπὸ τὸ ἀκόντιον ὑπελθεῖν· ὁ δὲ νεανίσκος οὐδὲν περισσὸν τούτων ἁμαρτών, ὁμοίως τούτοις οὐκ ἂν ἔβαλεν αὐτὸν ἀτρέμα σὺν τοῖς θεωμένοις ἑστῶτα. ... μεμνημένοι τοῦ πάθους ὅτι διὰ τὸν ὑπὸ τὴν φορὰν τοῦ ἀκοντίου ὑπελθόντα ἐγένετο, ἀπολύετε ἡμᾶς· οὐ γὰρ αἴτιοι τοῦ φόνου ἐσμέν. I will show that he is no more a participant in the homicide than his fellow javelinthrowers. If the boy died because he threw, all those practicing with him would be sharers in the responsibility: they failed to hit him not because they did not throw but because he did not run under any of their javelins. The young man no more committed an error than they did; just like them, he would not have hit the boy if he had stood still with the spectators. ... Remember that the unfortunate incident occurred because of the one who went under the path of the javelin, and acquit us, since we are not responsible for the killing. 10. Antiphon 6.2 (cf. 5.14): καὶ τοὺς μὲν νόμους οἳ κεῖνται περὶ τῶν τοιούτων πάντες ἂν ἐπαινέσειαν κάλλιστα νόμων κεῖσθαι καὶ ὁσιώτατα. ὑπάρχει μὲν γὰρ αὐτοῖς ἀρχαιοτάτοις εἶναι ἐν τῇ γῇ ταύτῃ, ἔπειτα τοὺς αὐτοὺς αἰεὶ περὶ τῶν αὐτῶν, ὅπερ μέγιστον σημεῖον νόμων καλῶς κειμένων· ὁ χρόνος γὰρ καὶ ἡ ἐμπειρία τὰ μὴ καλῶς ἔχοντα διδάσκει τοὺς ἀνθρώπους. All would praise the laws established for such matters as the finest and most hallowed of laws. For they are the oldest in this land, and moreover they have always been the same regarding the same things, which is the greatest indication of well-enacted laws, since time and experience teach men what is not right. 8