Alan Cameron ...

advertisement

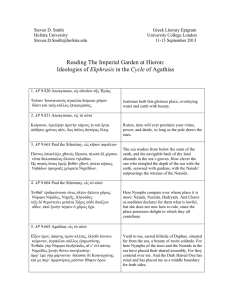

Alan Cameron Palladas and Pagan Statues 1) Λίτραν ἐτῶν [a pound of years] ζήσας μετὰ γραμματικῆς βαρυμόχθου βουλευτὴς νεκύων πέμπομαι εἰς Ἀΐδην (AP xi. 97). There were 72 solidi to a pound of gold. 2) Χριστιανοὶ γεγαῶτες Ὀλύμπια δώματ’ ἔχοντες ἔνθαδε ναετάουσιν ἀπήμονες· οὐδὲ γὰρ αὐτοὺς χώνη φόλλιν ἄγουσα φερέσβιον ἐν πυρὶ θήσει. By converting to Christianity the gods whose dwellings are on Olympus are living here free from danger. The melting-pot that produces life-sustaining pennies will not consign them to the fire. AP ix. 528, εἰς τὸν οἶκον Μαρίνης. 3) Deos istos aut monetae ignis aut metallorum coquat flamma. Let the fire of the mint or the blaze of the quarries melt down those gods. Firmicus Maternus, De errore prof. relig. 28. 6. 4a) “the only context that fully explains Palladas’ poem” is Constantine’s confiscation of “the precious metals belonging to pagan temples—their doors, their roofs, and especially their statues” (my italics)... 4b) The usual fate of pagan statues captured by Constantine was to be turned into coins, but some brazen gods managed to avoid this end by converting to Christianity—that is, by leaving their pagan cult behind and taking up residence in the new Christian capital [ἔνθαδε] of this very Christian emperor. The epigram is a clever and surprisingly insouciant confirmation of the more pedestrian accounts in our prose sources. 5) “the statues of pagan deities were either placed in a Christian context in the Christian city of Constantinople or turned into coin.” (T. D. Barnes, Constantine: Dynasty, Religion, and Power in the Later Roman Empire (Oxford 2011), 130.) 6) The sacred bronze figures, of which the error of the ancients had for a long time been proud, he displayed to all the public in all the squares of the Emperor’s city [Constantinople], so that in one place the Pythian [Apollo] was displayed as a contemptible spectacle to the viewers, in another the Sminthian [Apollo], in the hippodrome itself the tripods from Delphi, and the Muses of Helicon in the palace. The city named after the emperor was filled throughout with objects of skilled artwork in bronze dedicated in various provinces. To these under the name of gods those sick with error had for long ages vainly offered innumerable hecatombs and whole burnt sacrifices, but now they at last learnt sense, as the Emperor used these very toys for the laughter and amusement of the spectators (ἐπὶ γέλωτι καὶ παιδιᾷ τῶν ὁρώντων). Another fate awaited the golden statues. Eusebius, Vita Constantini 3. 54-58. 7) “When he perceived that the masses, like silly children, were terrified by bogeys fashioned from gold and silver” (LC 8. 1; VC 3. 54. 4), he had the precious cladding scraped off and melted down, “leaving what was superfluous and useless as a memorial of shame to the superstitious worshippers” (LC 8. 3), “depriving them of their fine appearance and revealing to every eye the ugliness that lay beneath the superficially applied beauty” (VC 3. 54. 6). 8) Such of the statues as were of precious metal or whatever else seemed useful were melted down by fire and turned into money; but beautifully crafted bronze statues were taken to the city named after the emperor from all quarters to adorn it (τὰ δὲ ἐν χαλκῷ θαυμασίως εἰργασμένα πάντοθεν εἰς τὴν ἐπώνυμον πόλιν τοῦ αὐτοκράτορος μετεκομίσθη πρὸς κόσμον). Sozomen, Hist. Eccl. ii. 5. 3. 9) χαλκοτύπος τὸν Ἔρωτα μεταλλάξας ἐπόησε τήγανον, οὐκ ἀλόγως, ὅττι καὶ αὐτὸ φλέγει. The coppersmith has turned Cupid into a frying-pan, reasonably enough, because it too burns (AP 10) The statues [of Maximin]...were cast down and broken in the same manner, and lay as an object of merriment and sport (γέλως καὶ παιδιά) to those who wished to insult or abuse them. Eusebius, Hist. Eccl.ix. 11. 2. 2 11) Many envoys from Asia and Achaea, who happened at the time to be in Rome serving on deputations, were paying worship (venerabantur) to images of their gods that had been carried away from their own sanctuaries and [were now] in the Forum (deorum simulacra ex suis fanis sublata in foro venerabantur). Cicero, In Verr. ii. 1. 59. 12) dedicatur Constantinopolis omnium paene urbium nuditate, Jerome, Chron. s.a. 324. 13) παίγνιον πέλειν πόλει / παισίν τ’ἄθυρμα καὶ γέλων τοῖς ἀνδράσιν, Constantine the Rhodian Ecphr. 151-52, on the Athena Lindia. 14) τὸν Διὸς ἐν τριόδοισιν ἐθαύμασα χάλκεον υἷα, τὸν πρὶν ἐν εὐχωλαῖς νῦν παραριπτόμενον. ὀχθήσας δ’ ἄρα εἶπον· Ἀλεξίκακε, τρισέληνε, μηδέποθ’ ἡττηθεὶς σήμερον ἐξετάθης. νυκτὶ δὲ μειδιόων με θεὸς προσέειπε παραστάς· καιρῷ δουλεύειν καὶ θεὸς ὢν ἔμαθον. I was astonished to see the brazen son of Jove at the cross-roads, once in everyone’s prayers but now tossed aside. In wrath I spoke: “Averter of woe, product of three night’s labour, you who never suffered defeat, now laid low.” But the god just smiled; at night he stood by my bed and said: “Even though I am a god I have learned to serve the times” (AP ix. 441). Bibliography: a) Kevin W. Wilkinson, “Palladas and the Age of Constantine,” JRS 99 (2009), 36-60; “Palladas and the Foundation of Constantinople,” JRS 100 (2010), 179-95. b) Cyril Mango, “Antique Statuary and the Byzantine Beholder,” DOP 17 (1963), 55-75; G. Dagron, Constantinople imaginaire (Paris 1984), 127-59; T.C.G. Thornton, “The destruction of idols—sinful or meritorious?” JTS 37 (1986), 121-29; H. Saradi-Mendelovici, “Christian Attitudes toward Pagan Monuments in Late Antiquity,” DOP 44 (1990), 47-61; Liz James, “Pray Not to Fall into Temptation and Be on Your Guard: Pagan Statues in Christian Constantinople,” Gesta 35 (1996), 12-20; Béatrice Caseau, “Rire des Dieux,” in E. Crouzet-Pavan and J. Verger (eds), La dérision au Moyen Âge (Paris 2007) and “Religious intolerance and pagan statuary,” in L. Lavan and M. Mulryan, The Archaeology of Late Antique Paganism (Leiden 2011), 479-502.