ARTICLE Gerry W. Beyer Avoid Being a Defendant: Estate Planning Malpractice and

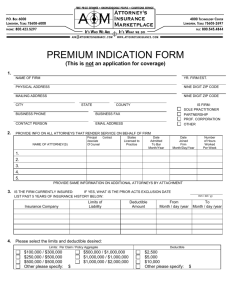

advertisement