PET ANIMALS: WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THEm IruMANSDIE?

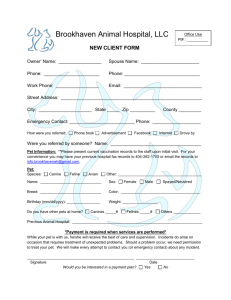

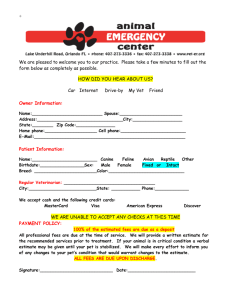

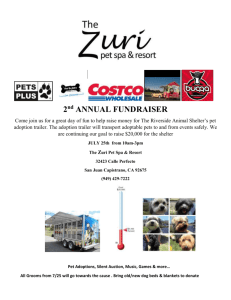

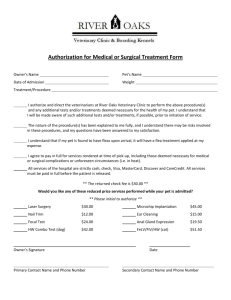

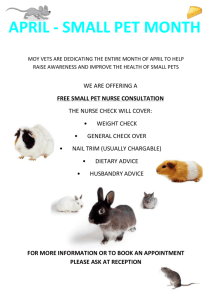

advertisement