Witness to Pearl Harbor Amazing feats of engineers Student haute cuisine

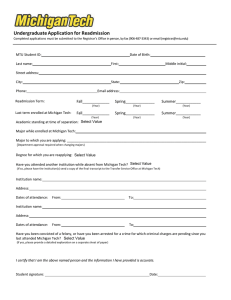

advertisement