T L S D

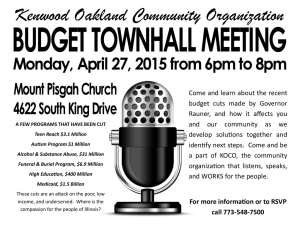

advertisement