MONASH PRATO STUDY ABROAD RESEARCH PROJECT FINAL REPORT 2011-2012

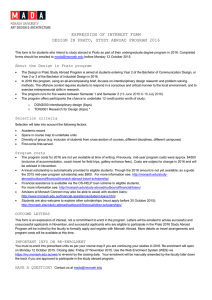

advertisement