Business as usual? The Barnett formula, 155 IFS Briefing Note BN

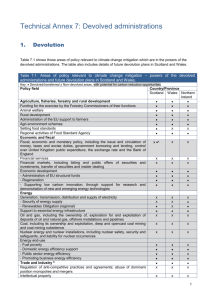

advertisement