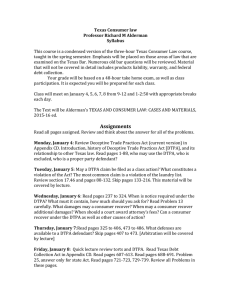

THE 1995 REVISIONS TO THE DTPA: ALTERING THE LANDSCAPE 1442 1444

advertisement