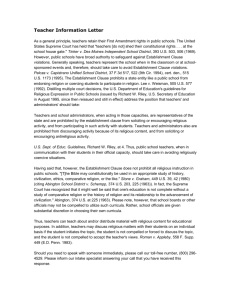

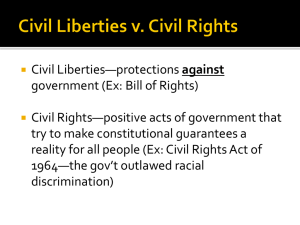

MORALS LEGISLAnON AND THE ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE

advertisement