Dividing what was once inseparable

advertisement

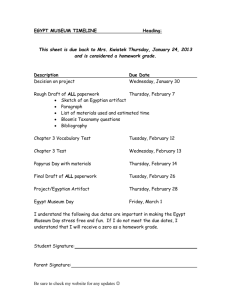

Dividing what was once inseparable Multi-cultural Egypt between disciplinary boundaries and Western typologies Heba Abd El Gawad, Durham University I. Outline There are two great modern cities in Egypt, Cairo and Alexandria. Both were established by foreign regimes that had Egypt at the core of their empire. Cairo was founded by the Fatimids in the 10th century AD, while Alexandria was founded by the Ptolemies during the 4 th century BC. Each city was a dynastic power centre and a theatre for the state’s dramatic representation in the eyes of the world. Cairo and Alexandria were not only dynastic monuments for the Fatimids and the Ptolemies; they were also multi-cultural centres reflecting the mixture of cultures and ethnicities co-living in Egypt during both periods. The multi-cultural nature of Fatimid Cairo is still vivid in the surviving alleys of Old Cairo, with the Coptic churches standing next to the Fatimid mosques, leading to a more balanced assessment of the cultural co-existence and its impact on the archaeology and history of the era. Sadly, very little evidence is left of the mixed cultural hustle and bustle that was Ptolemaic Alexandria leading to much misinterpretations of the nature of the material from Ptolemaic Egypt. This paper attempts to draw a picture of the existing approaches to multi-cultural Ptolemaic Egypt- in particular the royal representations- and the impact of such approaches on the contemporary scholarly and public attitudes towards the period. To this end, royal Ptolemaic objects kept and displayed at the British Museum are used as a case study of how the reformation of objects based on Western typologies and disciplines entails a change in the value and meaning of the cultural context within which the objects were originally embedded. The paper intends to highlight the role Ptolemaic objects should play in “forming material Egypt” and how an alternative contextual approach is much needed to reach a more balanced understanding and appreciation of the impact of the era on ancient Egypt. I. Approaching Ptolemaic Objects: Problems and Gaps The Ptolemaic period has for more than a century had a strong presence in academia, but it has often been isolated from the study of other periods of ancient Egypt. This isolation stems from a variety of causes. Ironically, the richness of the source material from the period and its multidisciplinary nature has been the strongest of these. Scholars naturally want to specialise and the material from Ptolemaic Egypt creates opportunities for many specialists indeed. But in the process of specialisation the forest is often lost for the trees. A second, perhaps more pressing reason for Ptolemaic Egypt’s isolation from the rest of Egypt’s dynastic history is the prevailing understanding of Ptolemaic Egypt being a place apart, so distinctive, due to the Greeks presence and their assumed “domination”, that its history and material culture has always followed a different course. According to this line of argument, Egypt has produced essential documents, but these can only be understood in terms of the power struggles between the foreign kings and the indigenous groups with all the royal representations being labelled as simple accommodation or adaptation to Egyptian traditions. These attitudes towards the Ptolemaic history and the resulting material culture are strongly mirrored within the museum environment and the methods used to disperse and display the objects. Objects which are defined “art-historically” as being Egyptian are often kept and displayed within Egyptian galleries, while those labelled as being Greek -even if being retrieved from same provenance- rest with purely Greek objects. Such attitudes must have surely had an impact on the study of the period and on how the Ptolemaic period should be perceived and understood between the academic and public spheres. The distinction made between Egyptian and Greek style representations stems from the Western perceptions of the Ptolemaic period in terms of the romantic division between “East” and “West”. Much of this dichotomy has carried over into modern views of Ptolemaic Egypt from the observations of ancient Greeks like Herodotus, who drew contrasts between Egypt and Greece for particular political and social purposes. A contextual analysis of the Ptolemaic material culture, within the micro scale of ancient Egypt and the wider scale of the Hellenistic world and pre-modern states will give us occasion to rethink of the typologies generated as a result of our modern experiences and the impact of our disciplinary boundaries on our understanding of the past. This will lead us to reconsider what can be identified as Egyptian, Greek or even Hellenistic, with the latter term being the most problematic. “Hellenistic” has often been ciphers for an historical period that was something less than “Hellenic-Greek-like” yet not fully Greek. The terms which we have imposed on this 2 historical period and its material culture hardly do justice to what Alexander the Great and his successors had in mind. The world, then, was a fertile ground for the interaction of cultures and institutions. The cultural contact was, indeed, a two way process, involving not merely the spread of Greek culture to the “East”, but also cultural and institutional negotiations that produced several kinds of responses, between acceptance and rejection, and many things in between. To this end, the Ptolemaic period was not merely Egyptian, although Egyptian culture played a vital part in it. And it was not only Greek, although it was that as well. It combined the traditions of both cultures creating a new cultural and political outlook which should be referred to as being simply Ptolemaic, a definition that reflects the “hybrid” nature of the state and its audiences. This “hybridity” is now becoming increasingly clear in the archaeology of the capital Alexandria, where an extensive amount of the objects retrieved in the underwater excavations are of -what is perceived as- pure Egyptian iconography in art-historical terms (see for example Goddio 1995, 1998, 2006; Empereur 1998). Yet despite these telling discoveries, the debate among scholarly networks is mainly concerned with whether the recovered sculptures were moved to Alexandria from earlier sites or they are of a Ptolemaic manufacture date (Ashton 2001; Stanwick 2002). This fact is only secondary to the point that both Egyptian and Greek ideologies were incorporated in the royal image in the Ptolemaic metropolis. It makes little sense, then, to continue to make a distinction between the Greek and Egyptian representations of the Ptolemaic kings. Such stark distinctions are no longer productive, and in the case of Ptolemaic Egypt, modern theoretical and methodological advances in cultural theory and political communication between foreign and indigenous groups offer variables and “points of concern” that can help us reach a better understanding of the mixed iconography and multicultural nature of the objects rather than relying mainly on art-historical dating and identification of cases of complex ethnic identity. The framework of the royal image was far more complex and built on power relations and dynamics which cannot be substituted by the simple art-historical typology of pure Egyptian, pure Greek or mixed Greek and Egyptian. These objects were the middle agencies of a communication process which involved planning, audience identification, choice of suitable medium, setting, and reception. To identify and display them on the basis of an artistic genre is to tell us what we can already see. Art-historical approaches are invaluable for dating objects, yet 3 they offer only partial interpretation of how these objects “lived” in their contemporary environment. I.1 Royal Ptolemaic Objects at the British Museum: A Case Study The British museum holds one of the world’s largest collections of Ptolemaic objects (3610 artefacts) of different strands of source material. Given the extent of the Ptolemaic sphere of influence the find spots of the objects varied between Egypt, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean. Our concern here is the royal Ptolemaic objects retrieved from Egypt and how they are displayed in the ground level. Royal Ptolemaic objects in the ground level are divided between two galleries, gallery 4, Egyptian sculpture, and gallery 23, Greek and Roman sculpture (see Figure 1). Figure 1 Plan of the ground Level of British Museum with Ptolemaic objects being displayed in galleries 4 and 23 4 Royal Ptolemaic objects at the British museum varied between statues, stelae, temple reliefs, rings, cameos, coins and foundation deposits. “Egyptian” style statues, stelae and temple reliefs are kept within the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan while the “Greek” style iconography retrieved from Egypt is placed within the Department of Greek and Roman antiquities. While the division of the objects within the two departments could be understandable given the scholarly background needed to handle, date and conserve the various objects, yet it is problematic when it comes to display. If we attempt to reconstruct a visitor’s experience of the Ptolemaic history as projected by the display at the British museum’s ground level, we will find ourselves receiving divided, if not confusing, messages. The first stop would be gallery 4 where we would be confronted by the Rosetta stone (see no. 33 in black in Figure 1), a key object for the understanding of ancient Egypt and the evolvement of the discipline of Egyptology. The audio description of the piece highlights the overall historical setting, yet little emphasis is being put on the bilingual nature of the era as a result of the multicultural environment to which we owe much of our decipherment of ancient Egypt. Emphasis is placed mainly on the Egyptian priesthood, while the fact of the priestly synods being a Ptolemaic “dynastic signature” is to a great extent ignored. This raises the issue of the relation between objects and words in museum display. While the objects are loaded with communication messages, yet such messages could only be translated by the holders of knowledge. This was the case in the past and still is in the present. Literacy levels and access to ancient “power space” was restricted to the inner elite, even those who had access would still need the messages to be deciphered to them probably through oral tradition. Similarly, the objects in the museums today need to be mediated to the public through labels and audio descriptions or through tour guides. Thus, the descriptions, no matter how brief, play an integral role in the communication process between museum visitors and the objects displayed. The Rosetta stone is being displayed among objects dating to earlier periods of ancient Egyptian history. The Rosetta here is identified in terms of its discovery and importance to the field and is totally isolated from its contextual historical, political and cultural history making it difficult to recapture how it featured within its contemporary settings. One of the important missing facts is the original geographical setting and its instalment within the temple, which are all ever so important episodes of the whole drama within which the object originally existed. While the 5 British museum has devoted several publications for the Rosetta stone with extensive details on its discovery and translation of its text (Andrews 1982; Andrews and Quircke 1988; Parkinson 1999, 2005), yet the day visitor would mainly rely on the information offered by the label or audio description. Our second and last stop in gallery 4 is at the western end of the gallery leading to western stairs where the rest of the Ptolemaic “Egyptian sculpture” is being displayed. The material displayed there is mainly stelae with either royal dedications to particular deities or non royal stelae which are evidence of “personal piety” towards Ptolemaic royal cult. The labels, again, offer very little information, especially on the dynastic ruler cult ‘invented’ by the Ptolemies and the indigenous priesthood. One of the artefacts which perfectly depict the impact of western typologies of arthistory and the impact of undefined discipline boundaries on the understanding and interpretation of objects with mixed cultural iconography is EA 1056 (Figure 2). Figure 2 ex-voto depicting Ptolemy II and his sister-wife Arsinoe II as Theoi Adelphoi EA1056 courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum 6 This limestone ex-voto is defined on the label as a temple relief referring to Petrie’s comments upon discovery. Yet, the measurements and the parameters would not qualify it as a temple relief. Given the size, craftsmanship and the context it was discovered in at Tanis, the piece could be identified as an ex-voto. The piece depicts Ptolemy II (285-246 BC) and his sister-wife Arsinoe II (270 BC) as Theoi Adelphoi as brother-sister loving gods. The importance of the piece lies in the object being held by Ptolemy II in his left hand which is the thunderbolt of Zeus, a purely Hellenistic symbol being depicted on a purely Egyptian setting. The imagery depicted on this limestone slab summarises the values and ideologies of Ptolemaic kingship in one scene: a) the prominent position of the queens, especially Arsinoe II; b) the deification of the Ptolemaic kings and queens; c) the fusion between the Egyptian and Greek ideologies creating a new form of kingship. Little emphasis is placed on the importance of the piece, despite of it being a visual proof of the multi-cultural nature of Ptolemaic Egypt. Scholarly debates on this piece are mainly concerned with the dating of the piece (see, e.g., Bianchi 1989). Again, this is secondary to the appearance of a Hellenistic element within the confined conservative environment of the Egyptian temple. The final destination in our tour of the royal Ptolemaic objects at the British museum’s ground level would be at gallery 23. This gallery displays mostly objects retrieved from Alexandria which are closely connected to the Ptolemaic ruler cult. Two interesting pieces that can complement our Tanis Limestone slab of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II is the bronze statuettes of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II, this time in what is perceived as pure “Greek” format (Figure 3). The bronze statuettes are another visual representation of Ptolemy II and his sister-wife Arsinoe II as gods. The representation according to art-historical typologies is purely Greek. What interests us here is how this representation communicates the same ideology in the Tanis limestone slab yet to a different audience. Both the Tanis slab and the bronze statuettes here coexisted in Ptolemaic Egypt. The fact that one is in a pure Egyptian format and the other in a Greek format is only minor. The message being communicated by the museum display is that Alexandria was a place apart, a “superficial” visual analysis of a much more complicated situation. 7 Figure 3 Bronze statuettes of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II BM 38442 courtesy of the trustees of the British museum A display with all the above mentioned pieces side by side would surely reflect a more balanced image of Ptolemaic Egypt. I.2 Cleopatra: The “only” Face of Ptolemaic Egypt? On the other hand, Ptolemaic Egypt has always had Cleopatra. In this instance both the museum and the academic spheres are being driven by the public. Cleopatra has been the subject of numerous biographies, and spectacular exhibitions (see, e.g., Walker and Higgs 2001; Bianchi 1989). Exhibitions featuring the Ptolemaic period are normally focused around the figure of Cleopatra with most of the exhibition titles referring to Cleopatra as the only face of Ptolemaic Egypt. While part of the function of museum exhibitions is to draw more visitors which explain the wider appeal the exhibition has to attract, yet most of the pieces being exhibited are of earlier male and female predecessors to Cleopatra. The evidence of Cleopatra is quite scarce given the limited archaeological evidence related to her that has been discovered so far. Additionally, 8 Cleopatra’s reign marks a shift in the history of the Ptolemaic period and its relation to Rome, one of the many political episodes the Ptolemaic history has gone through. The Ptolemaic period is rich with prominent figures that had much more impact on the world stage than Cleopatra. The extensive recycling of Cleopatra as the only face of the Ptolemaic period could be described as an exercise of creating a ‘false history’ of the era which is being led by popular culture rather than leading it. II. Towards a more balanced Approach A more balanced approach could be achieved without having to face the difficulty of redesigning the galleries or moving objects around. A reconsideration of the labels being placed beside the objects with small images beside each set of objects referring the viewer to objects of the same period at other galleries within the museum would be an easy solution that would not incur much extra cost on the museum. This can simply be done by volunteers of the relevant expertise who can write more personalised labels beside each object, rather than the systematic formal labels currently on display. A database incorporating material dealing with a certain aspect of the history and culture of Ptolemaic Egypt from various find-spots would offer a visual aid that would help shape a more balanced approach to the multi-cultural periods of ancient Egyptian history. A similar project is being held by the British museum on the site of Naucratis and the status of the Greeks in Egypt. Future projects with similar outputs would help promote the less “famous” periods within ancient Egypt and offer a new means of understanding cultural interaction in the past. The story each museum display presents, and which visitors experience consolidated collective memories of the past, it continues to influence how the past is perceived and imagined. In this respect, display of Ptolemaic objects has been mainly based on art-historical categories which tell us what we can already see. Additionally, they divorce the viewer from the real story behind the object, with the artefacts of the same historical and contextual background being separated in time and space. If museums seek to reduce the distance between people and things, displays and interpretations should be displayed in such a way to facilitate a wider or deeper sensory and intellectual engagement with the objects, rather than simply enable comprehension of a story or set of facts presented by the museum and merely illustrated or punctuated by the object, in order to allow the 9 viewers to appreciate more the aspects of both the object and the story it tells. We need to rethink which story an object should tell in a museum, our story or its own. Bibliography Andrews, C.A.R. 1982. The Rosetta Stone. London. Andrews, C.A.R. and Quirke, S. 1988. The Rosetta Stone: facsimile drawing. London. Ashton, S. A. 2001. Ptolemaic royal sculpture from Egypt: The interaction between Greek and Egyptian traditions. Oxford. Bianchi, R.S. 1989. Cleopatra’s Egypt: Age of the Ptolemies. Brooklyn. Empereur, J.V. 1998. Commerce et artisans dans l’Alexandrie Hellenistique et romanine. Actes du colloque d’Athenes 11-12 decembre 1988. Bulletin de Correspondance hellenique Supplement 33. Athens. Goddio, F. 1995. Cartographie des vestiges archaeologique submerges dans le Porte east d’Alexandrie et dans la Rade d’Aboukir. In Amedeo Tullio, Cristiano naro, and Elissa Chiara Portale (eds) Alessandria e il mondo ellenistico-romano, I centenario del Museo Greco-romano: Alessandria, 23-27 Novembre 1992, atti del II Congresso internazionale italo-egiziano, Rome: 172-175. Goddio, F. 1998. Alexandria: the submerged royal quarters. London. Goddio, F. 2006. Egypt’s sunken treasures. Munich. Parkinson, R. 1999. Cracking codes: the Rosetta Stone and decipherment. London. Parkinson, R. 2005. The Rosetta Stone. London. Stanwick, P. E. 2002. Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek kings as Egyptian Pharaohs. Austin. Walker, S. and Higgs, P. 2001. Cleopatra of Egypt: from history to myth. London. 10