Document 12831975

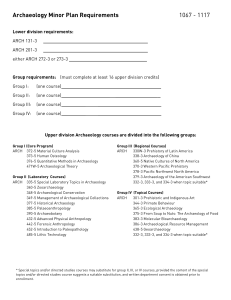

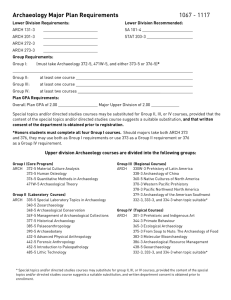

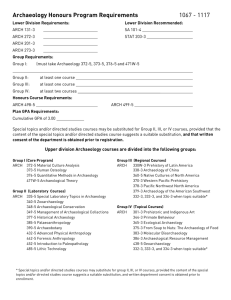

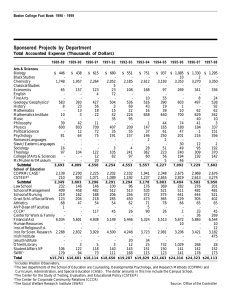

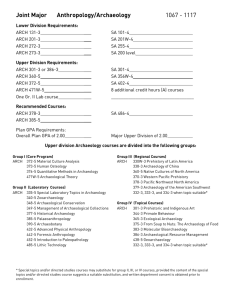

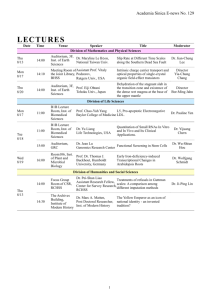

advertisement