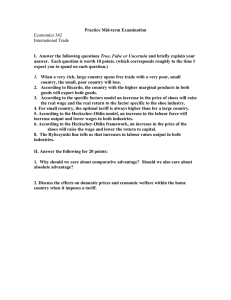

T R W I

advertisement