LITHIC ANALYSIS MA COURSE (15 credits): ARCLG113 COURSE HANDBOOK 2014

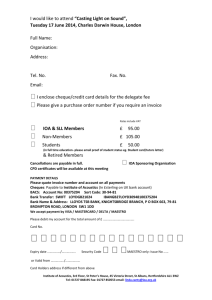

advertisement