Assessing the economic benefits of education: reconciling microeconomic and macroeconomic approaches

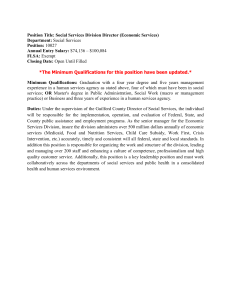

advertisement