AVOIDING THE ESTATE PLANNING "BLUE

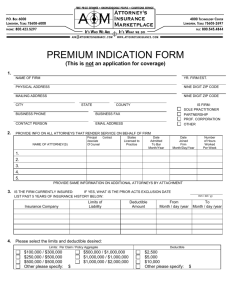

advertisement