International student mobility literature review

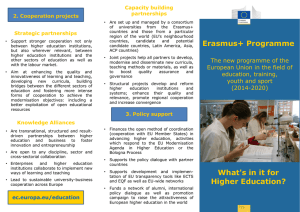

advertisement