Queer Sinophone Cultures Edited by Howard Chiang and Ari Larissa Heinrich Routledge

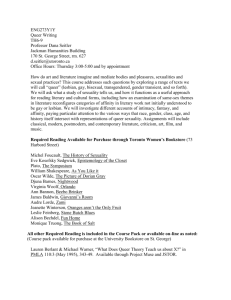

advertisement