An Evaluation of the Impact of the Social Education Outcomes

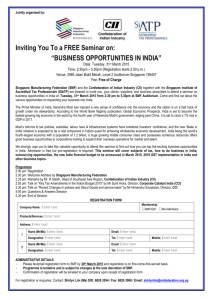

advertisement