Developing the role of school support staff The Consultation

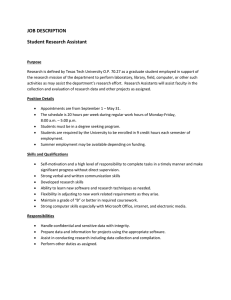

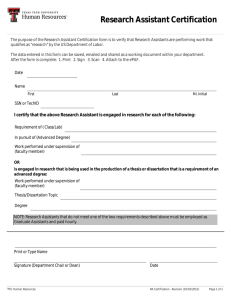

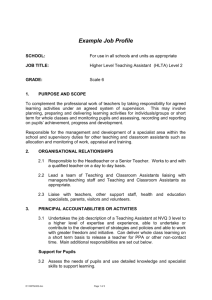

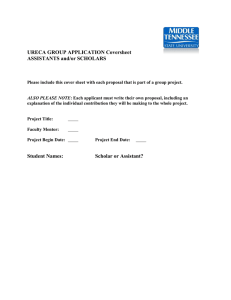

advertisement